The pages of space travel history are filled with records of countless animals and insects who were sent into space.

Perhaps the most famous was Laika, the cosmonaut dog sent into orbit on Sputnik 2 in 1957. She became the first animal to ever enter space, and her journey sparked a flurry of other tests that eventually led to the first human space trip in 1961.

But, why do scientists send animals into space, anyways? And what do recent medical discoveries like intestinal liquid ventilation mean for the future of space travel?

Why Perform Animal Testing in Space?

Animal testing has polarized the science community. On one side, the human safety activists argue that animal testing helps protect us from harmful side effects of pharmaceuticals, cleaning supplies, and pretty much every other product under the sun.

On the other side of the spectrum, the animal rights activists argue that there are other ways to safely perform tests that doesn’t cost lab animals their lives.

There are valid points on both sides of the argument, but sending animals to space has sort of become the posterchild for both animal testing and abolishing animal testing.

So why do we send dogs, chimps, and spiders to space to begin with?

In the early days of the space race, scientists were uncertain about the conditions in space. There were a lot of unanswered questions:

- Could humans survive the g-force of entry and reentry?

- Would the human body withstand the stress of a prolonged space trip?

- How would the body readjust to Earth’s gravity?

Bioastronautics specialists figured that the road to these answers was simply to send various creatures into orbit and observe the results. Unfortunately, almost all animals sent into space died from the stress. But their sacrifice led to the first human spacewalk, the first feet on the moon, and the development of the ISS.

What Kind of Creatures Got Tickets to Space?

While Laika was the first dog in space, she was followed by:

- 32 monkeys and apes (Ham was the first chimp in space)

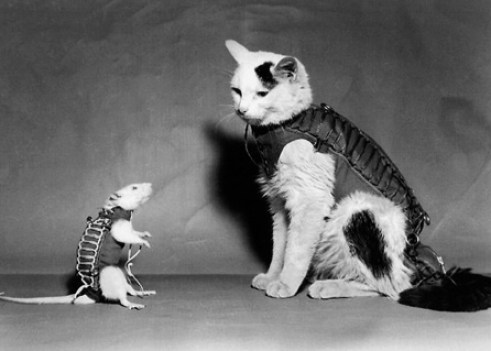

- Small mammals like dogs, cats, guinea pigs, and rabbits (Félicette was the first cat in space)

- Mice and rats

- Frogs, turtles, newts, and geckos

- Insects and arachnids (ants, fruit flies, orb spiders, etc.)

Photo from thenewstack.io

While no adult birds were brought to space, the American flight Discovery STS-29 took 32 chicken embryos into space.

Once scientists had a substantial amount of data about the effects of space on the body, they became interested in unborn creatures.

In addition to the countless live animals sent into orbit, scientists have sent quail and frog eggs into space, as well as the seeds for potatoes, cottonseed, and rapeseed.

But new studies have shown that certain animals have the capacity to breathe with much lower levels of oxygen than previously observed, which is obviously a plus when it comes to space travel.

Discovery of Intestine Breathing in Pigs and Rodents

A new study published in the medical journal Med presents the findings of how oxygenated liquid given to the intestines supported two mammals in respiratory failure.

Both pigs and mice were able to survive environments with critically-low oxygen levels because of oxygen tubes inserted through their rectums to reach the intestines.

Kind of absurd, right?

Well, scientists have known about non-lung respiratory functions for a while. Sea cucumbers and some freshwater catfish, for example, use their intestines to process oxygen. But until now, no mammals have been known to possess such abilities.

What does intestinal breathing in these mammals mean for humans? And what does it mean for the future of animal testing in space?

Medical Benefits of Non-Lung Breathing

The researchers who found the intestinal breathing capabilities of pigs, rats, and mice stated that the discovery might be used in the future to help human patients in respiratory failure.

75% of mice that were given the intestinal liquid ventilation system survived for almost an hour in oxygen-deficient environments, and in non-lethal oxygen-deficient environments, mice with the intestinal liquid ventilation were more active than mice without.

It’s still unclear whether or not humans have the same intestinal breathing abilities, but Takanori Takebe, head researcher of the project, said that “The level of arterial oxygenation provided by our ventilation system, if scaled for human application, is likely sufficient to treat patients with severe respiratory failure, potentially providing life-saving oxygenation.”

In the current medical climate, such a device might remedy the lack of ventilators for COVID-19 patients.

Thinking Outside the Box

As science fiction enthusiasts, we like to take real-world discoveries and bend them a little. In this case, the finding of intestinal breathing sparks questions about a functional use for it in the vacuum of space (or at least, in a space station).

Picture this: you’re on a spaceship in deep space, life support systems are failing and your friend is badly wounded. Oxygen is a precious commodity and you’re already running low. You have to keep your friend alive until backup arrives.

The intestinal liquid ventilation system can support your friend’s respiratory function while not consuming valuable oxygen gas. You’re able to keep him stable until rescue arrives.

While not the most realistic scenario, it’s perfectly feasible that in the future, intestinal liquid ventilation will be used to life-saving effect, not just on Earth, but in space too.

And who knows, maybe pigs and mice will be sent into orbit to test the ILV system before it’s approved for human use. While many of the animals sent to space lost their lives, their sacrifice made modern space exploration possible, and will continue to advance our trek beyond Earth.

One thought on “The History, and Future, of Animal Testing in Space”

Comments are closed.