So the story goes … that a high school student discovered a new planet (or exoplanet, to be exact) back in 2020, only 3 days into his internship with NASA.

Continue reading “He discovered a new planet … at 17 years old”Category: Scientific Advancement

Do You Smell That? … It’s Broccoli Gas

For as long as we’ve gazed up at the heavens and attempted to count the stars, that often posed, age-old question has continued to linger in the minds of our scientists and our SF authors …

Continue reading “Do You Smell That? … It’s Broccoli Gas”NFTs That Exchange Novelty for Utility

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) aren’t a new invention. They’ve been around in one capacity or another for a couple of years now. But they’re really getting popular now because of mainstream news outlets and investors on social media.

We’ve talked about some of the problems of NFTs before, but recently, there’s kind of been a shift in the way we think about NFTs.

A lot of the popular collections that have made press in mainstream media are purely artistic collectibles. They have no inherent value or purpose other than being a digital asset with a prescribed value.

When compared with cryptocurrency in general, these collectible NFTs serve far less function than a lot of people realize.

With Ethereum, you can purchase goods and services from online vendors (and some in-person places, too), hold onto it as an investment, or stake your ETH for interest.

With a collectible NFT, like a Bored Ape, you’re pretty much just holding onto it as a clout item or trying to flip it for profit. There’s not much else you can do with it.

That’s where many creators and crypto enthusiasts get caught up. Outside of the hype for these projects, what do they have to offer? And that’s where utility NFTs come into play.

Understanding NFT Utility

Where collectible NFTs have real no function other than being a novelty used by flippers to make a profit, utility NFTs come with some kind of inherent value or use outside of simply turning it around for a quick buck.

As a hypothetical explanation, let’s say you have a video game that relies heavily on weapon selection over real skill. The better gear you have, the better you are at the game.

We talked about how Counterstrike skins are like NFTs in the last blog, but they fall into the collectible NFT section. Other than adding cosmetic value, they don’t do anything else.

A utility NFT for a video game would be something you buy that has a use in-game that’s non-cosmetic. It could be a sword with reduced weight for faster swings, or a gun that has a higher rate of fire and more accuracy. These elements are what make the NFT useful, and that’s why people will buy them. Not only can they still look cool as a collectible item, there’s a functional purpose for owning them.

Additionally, some utility NFTs today provide more than just a digital asset. Some of them, like Jigen, provide an article of digital clothing for the Metaverse, as well as a physical edition of the clothing. You’re buying the NFT, but receiving both a digital and physical asset.

Why Adding Utility Solves Some NFT Problems

A lot of people that are serious about the NFT community always complain about the pump-and-dump schemes. Creators will hype up a project, profit off sales, and disappear, leaving buyers questioning the whole purpose of the project in the first place. The same goes for crypto tokens that started popping up after Dogecoin and Shiba Inu took the Internet by storm.

Utility NFTs solve this problem by providing users with a value other than an investment opportunity. With collectible NFTs, your use for them is controlled solely by market factors, much like a stock or other investment.

But with Utility NFTs, chances are you bought it for its functional purpose, and aren’t as concerned with the monetary potential in flipping it. This, overall, levels out the concerns a lot of people have with the NFT market.

Are we in a bubble right now? Will NFTs faze out in a few years when the novelty wears off? Maybe, but with an inherent use that gives value to users, NFTs will be a lot harder to rule out as a viable method of transferring goods and services.

Applications for Utility NFTs (In a Sci Fi Sense)

You might be wondering how many NFT projects actually have applications for the sci fi enthusiast, and it’s a reasonable question.

In a world that’s looking wackier and more dystopian every day, some utility NFTs can seem like they’re breaching privacy, weakening economic structures, and pulling the wool over the eyes of buyers.

Here are some examples of how utility NFTs are changing the digital landscape for good:

Nebula Genomics – This company is using blockchain technology to provide complete genome sequencing for people across the world. Where their counterparts collect and store DNA data—doing who knows what with it—Nebula Genomics makes their process 100% anonymous with a “blockchain-enabled multiparty access control system”. And, they’ve even shown they have the capability to turn complete genome sequences into NFTs, with their auction of Professor George Church’s genome data as an NFT.

Molcule.to – Where Nebula Genomics provides a service to the general public, Molecule is dedicated to provide top-tier research to medical and scientific professionals. On their website, Molecule states that it specializes in “funding, collaborating and transacting early-stage biopharma research projects”. Molecule allows researchers to connect with investors who will receive NFT data, and it facilitates the transfer of research between professionals in a decentralized marketplace.

Snapshot – Snapshot provides a secure, tested location for blockchain project owners to engage with their communities. Snapshot employs a gasless, blockchain-backed voting system, where members in the community have clear access to poll statistics about the future of their backed projects. This service assures full transparency for community-driven projects.

The Future of Utility NFTs is Bright

While there the market is still rampant with collections and projects that don’t have a clear end goal in mind, the NFT world is starting to develop a coherent purpose.

While not all NFT art collections are bad—like this street-art preservation project—utility NFTs are opening up the community for more scientific and purposeful projects.

Who knows, maybe in the future we’ll see NFTs change digital reading, online subscriptions, and other high-traffic industries.

For now, it’s safe to say that projects that exchange collectability for utility are bound to see more success than those purely invested in the novelty of the format.

The Tale of Two Sci Fi Cities

Just like there are multiple different genres of science fiction, there are also many imagined outcomes for the spaces where we live. In post-apocalyptic futures, survivors of nuclear fallout or deadly contagion hole up in abandoned buildings and underground bunkers.

For space opera sagas, people call space stations, colony ships, and mining rigs home. And cyberpunk cities are filled with smog, neon lights, and poverty. It’s clear that the spectrum of sci fi cities—or sci fi habitats, in general—are all dependent upon each individual value-set of the genre.

For example, cyberpunk has long been defined by end-game capitalism, where mega-corporations blatantly control governments and dictate the habits of the population. Any and all infrastructure projects are designed to benefit the corporations, and the everyday person ends up working longer hours for less pay, if they work a job at all.

The cyberpunk city reflects the high-tech, low-life motto of the genre. Tech isn’t used to create a better collective future, instead it’s the tool of authoritarian, capitalist regimes or the hobby of “punks” who see their individualism tied with technology.

Thinking about how political, economic, and social factors impact the kinds of cities we live in, I was interested to learn about the “real life” sci fi cities that pop up once and again in WIRED articles or news coverage.

More specifically, I am intrigued by the mindset that dictates the design choices for these cities. If we were living in a sci fi novel, what would our genre be? That’s how I wanted to look at the following sci fi cities.

Songdo IBD, South Korea

Songdo is one of the more popular sci fi cities you hear mentioned today, and it’s certainly on of the most complete. What started as a tidal flat home to a few fishermen, is now a “green” metropolis that houses around 170,000 people.

Songdo, and the Songdo International Business District, are located along the Incheon waterfront, an hour away from Seoul, South Korea. The city was designed to be a sustainable city, with green spaces and LEED-certifications galore.

In the past 20 years, multiple governments and investors have contributed $40 billion to Songdo city, making it one of the most expensive megastructures in the world.

The city, in keeping with the goal of environmental sustainability, features:

- Pneumatic waste systems that sort garbage and recycling

- A lofty 100 acres of park space

- Multiple LEED-certified buildings and spaces (approximately 106 buildings, when construction is complete)

- Bike lanes and accessible public transportation

Pictures of Songdo city might lure you into thinking it’s the future of urban living. The precursor to a solarpunk city, if you will.

However, under its bright green environmentalism, Songdo reveals the ideologies upon which urban life is built.

On an innocent level, sensors and built-in computers around the city monitor water flow, energy usage, and traffic patterns. This data is collected under the guise of advancement of green tech—gathering data to better perfect urban infrastructure.

But these auxiliary computer systems act as an appendage to the hand of authoritarianism. Throughout the city, government-funded cameras are mounted on light posts, street signs, traffic lights, and buildings, connecting back to the U-Life Center. What’s detailed as a precautionary measure to prevent crime and respond quickly to disasters can easily be equipped for intelligence-gathering and a demolition of any sense of privacy.

What’s more, Cisco, one of the developing partners, proposed that all children be equipped with GPS tracking chips in their bracelets. Albeit back in 2014, this tech is still just as haunting today, where it’s hard to find any kind of privacy from prying, online eyes.

Forest City, Malaysia

Just a six-hour plane ride from Songdo, another smart, green city is under development. Forest City is located in the Johor Bahru District in Malaysia, spanning around 3,400 acres. The project was meant to be an energy-efficient, low-waste city to help solve the growing population problem in Malaysia. Forest City was a collaborative effort between Johor People’s Infrastructure Group and Country Garden Holding Ltd.

Construction for the project began in 2006, but has stalled multiple times due to political, environmental, and economic factors. Environmentally, the construction project has compromised water hydrology, traditional fishing grounds, and mangrove orchards. And many experts are saying that the land is sinking, seen through cracks in new foundations and shifting buildings. The man-made islands weren’t given enough time to settle, and will create problems in the future.

Despite having raised over $100 billion for the project, Forest City remains one of the least populated cities in the world, with only about 500 full-time residents.

The idea for this sci fi city was sound—a metropolis filled with green spaces and next-level technology—but corruption and environmental oversight have landed Forest City in the margins of history.

A Capitalist Future

It’s clear that there are some strides being made toward sustainability and an environmentally-friendly future. However, there’s a difference between end-goal sustainability and continuous sustainability.

The land Songdo is built used to be a costal flat, with a few fishermen calling it home. Over the course of a few years, the whole landscape changed, with earthmovers bringing in tons of sand and soil to create the foundation for the city. And at one point, construction ground to a halt because it threatened local ecosystems.

And Forest City is no different. The man-made islands it sits upon were once an Environmentally Sensitive Area, which prohibited development that wasn’t related to low-impact tourism and research. Construction of Forest City began without the proper legal documents and eventually impacted coastal wetlands and traditional fishing families.

If these sustainable cities were more than a venture by capitalist well-doers, they would have taken the proper precautions to abide by local restrictions and environmental protection acts. In the pursuit of a “green city”, the developers have overlooked the biodiversity and importance of the coastal wetlands.

I think we can best sum up both Songdo and Forest City with a quote from Bruce Sterling, from his Manifesto of January 3rd, 2000. Talking about CO2 emissions—and largely about sustainable building practices—he says, “it’s not centrally a political or economic problem. It is a design and engineering problem. It is a cultural problem and a problem of artistic sensibility.”

Economically, these cities are possible. If not for capitalism, the Songdo and Forest City projects might not have raised billions of dollars from private and government investors. But culturally, the projects turned into vanity projects, and abide by the same autocratic policies that plague urban centers all over the world. Information privacy is thrown out the window, and the foundations for the cities were built using the same strategies as every other city.

The only way to truly create a green city, be it today or 10 years from today, is to start with a good foundation. That foundation is both a literal and a metaphorical thing.

You need to build in a place that’s not a protected environmental zone, obviously, but you also need to make the construction a collaborative effort between scientific and thought leaders in the field and local authorities. And under capitalism, that cannot happen. Corners will always be cut for the sake of profit, a focus will always be placed on recouping investment, and design elements will favor the needs of the state, or in this case, the developer.

If we learned anything from our deep dive into Solarpunk, it’s that the best places are built outside of the conventional sphere—with “punk” energy, if you will.

So, until those things happen, hopeful sci fi cities like Songdo and Forest City will only every be that: hopeful.

Will Near Future Sci Fi Lose Its Luster?

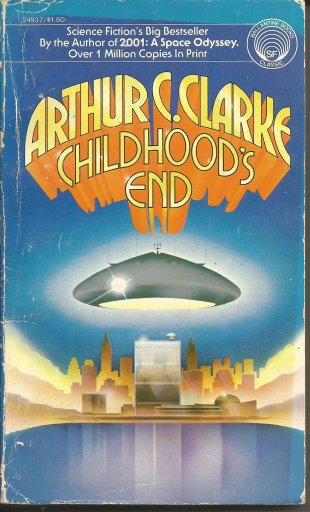

Recently, I’ve been reading Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, and I was struck by how old it seems. For me, at least, the true measure of an older science fiction novel is if it manages to maintain a certain level of credibility within the logical timeline I have running in my head.

Like, I read Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany, and yeah, it was published 60 years ago, but it never succeeds in placing itself anywhere in a coherent time or space I’m familiar with. There’s no bending of history to accommodate this novella, everything Delany writes could have happened, or still could happen in the future.

But with books like Childhood’s End, I can’t help but think about how it’s lost that security of time and special awareness. The book, published in 1953, starts out with US and Russian engineers in a race to put a military spacecraft into orbit. The way Clarke spins this, he makes it seem like it’s a big deal. The first craft in space! And he probably succeeded in hyping up his audience in 1953, because at that time the US and the USSR were in the middle of their Cold War rivalries.

As readers in 2022, however, we know that in 1957, Sputnik becomes the first space satellite to orbit the Earth. When Clarke’s timeline in Childhood’s End jumps forward, we present-day readers have to suspend our beliefs in order to keep going.

Dispelling any knowledge of the future as we know it after 1953 is sort of the antithesis of Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. We have to erase our minds and our beliefs to read Childhood’s End as a science fiction novel, not as an outdated alternate history.

And it got me thinking about near future sci fi books in general. In how many years will we look back at science fiction books and movies that speculated on our near future and say “nah, that’s just not it”?

Or, will we engage in the active purging of our memories when reading these books to accommodate the timeline and scenarios that may have already come to pass, whether true or not?

How Near Is the Near Future?

Obviously, science fiction spans across multiple different subgenres and niches, some of which specialize in far future scenarios, thousands of years after humanity will be dead and gone. Others hit closer to home, waxing clairvoyant about ten, twenty, or fifty years into the future.

Some sci fi concept novels or movies make a point of clearly specifying a time and place of the story, so much so that the time has become part of the story’s identity.

Blade Runner: 2049, for example, or even Cyberpunk 2077. These works make the time in which they’re situated part of the premise. Just thinking about the future will get people to consider these works as the blueprints for the years 2049 or 2077.

Other works get even closer to our current time in space. The Martian predicts colonization efforts on Mars by 2035, while Constance brings human cloning to the forefront in 2030.

As these authors get closer and closer to our present day, the likelihood of their speculations coming to fruition gets smaller and smaller.

Near future sci fi books act as a kind of playful challenge to the science community. “Do you think you can perfect human cloning and commercialize it by 2030? I bet you can’t.”

But here we have to dive a bit deeper, look directly into the face of the question: what’s the purpose of near future sci fi, anyways?

The Art of False Predictions

Cory Doctorow talks about how sci fi authors predict the future in an essay that was published as part the Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds. An excerpt was published on Slate.com, where he notes that:

“When it comes to predicting the future, science-fiction writers are Texas marksmen: They fire a shotgun into the side of a barn, draw a target around the place where the pellets hit, and proclaim their deadly accuracy to anyone who’ll listen.”

And he’s right. Sometimes a sci fi author will get wildly lucky and hit the nail on the head, winning the million-dollar prize and fame forever.

But most times, predicted, imagined futures will pass us by every day without any grand hoorah, ending up in a catalogue of unfulfilled timelines.

And then there’s the in between-realm. The few science fiction legends who had enough common sense and foresight to predict what our future would be like in the next 50 to 100 years. Arthur C. Clarke predicted 3D printing, Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick predicted something like the internet that would connect the whole world.

But, here’s the fun part. These guys, they’re still shooting that double-barrel shotgun from the hip with a Sharpie in their teeth.

It’s easy to make a broad speculation about the future based on events in the past and the current state of science.

For the Golden Age sci fi writers, looking back at the technology of their childhood, and then looking at the world they were living in, it must have been fairly easy to assume what was coming next. Radio, telephones, television—those things were shaping the world in sci fi’s heyday. To look forward and think about a more advanced transfer of information from person to person, a method that’s faster, is only natural.

Does that mean Clarke, Asimov, and Dick predicted Facebook? Absolutely not.

And I think that’s where we find the answer to our titular question: Will near future sci fi books lose their luster?

The Devil’s In The Details

The reason I started thinking about this question of longevity of sci fi books is because Childhood’s End made me recondition my knowledge of history to read it without skepticism. The future for Clarke is distant history for me.

And I assume people in the year 2060 will look back at Blade Runner: 2049 and laugh, knowing that their lives are either much better or much worse than they were imagined to be back in 2017.

Films and books like that, in this regard, made the mistake of being too specific. The first rule of sci fi predictions is to never timestamp anything. Had the film been named Blade Runner 2, perhaps people might have been able to extend the possibility of a near future where Replicants and Blade Runners walk the streets.

The Golden Age crew thought up something like the Internet, but they didn’t specify when it would be created, who was going to do it, what it would be called, etc. So, in many ways, they were right.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that near future science fiction books will always make predictions about a time and place and a technology. When we come across a book like Childhood’s End where we as the reader are required to willfully ignore recent history for the sake of the story, just know that that author fell prey to the camp of specificity.

And we can’t wholly discount these once-could-have-been-futures, either. In 2060, we’ll probably look back at The Martian, Constance, Blade Runner, all of them and take something from them. It won’t be a slice of science history, rather a note about the human experience, something we can relate to even though we might be living in a world none of our sci fi authors could have imagined.

Understanding Sci Fi Subgenres: Gothic Science Fiction

Aaaand we’re back to break down more sci fi subgenres, this time we’re delving into the creepy, weird world of gothic science fiction!

For many people, hearing the words ‘gothic science fiction’ brings back memories of high school English class and Mary Shelley’s magnum opus, Frankenstein.

And certainly, Frankenstein is one of the pinnacle works in this sci fi subgenre, but it also largely inspired the genre as we know it today.

What is Gothic Science Fiction?

Gothic science fiction sits in that liminal space between two genres. On one hand, it takes a lot of aesthetics and themes from traditional gothic fiction, and on the other hand, it incorporates controversial or untested sciences to push the boundaries of creepy.

Gothic fiction dates back to the late 1700s and early 1800s, but has remained a steadfast genre to modern day. Where Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley, Eleanor Sleath, and Samuel T. Coleridge put the arcane into writing by candlelight, authors like Toni Morrison, Steven King, and Joyce Carol Oates brought the supernatural into the electric-light of modernity.

One of the staples of Gothic fiction has always been a fascination with the mysterious and the unexplainable. In Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), a massive helmet falls from the sky to kill one of the characters, and skeletal apparitions walk the castle halls at night. In many ways, the supernatural in Gothic fiction motivates characters to say and do things they might not normally do. Pure fear and confusion drive them to the ends of their wits, and this terror of human uncertainty is what makes Gothic fiction unique.

In modern horror, yes, motivations are driven by fear, but ultimately the unexplainable and the mysterious are more than just a catalyst. They’re a key component in the reaction of the reader or viewer.

Think of it like the difference between a jump scare and a lingering fear. When a demon or a ghoul lurches abruptly onto the screen, the audience lets loose a scream of horror. But when the fear builds up across the whole book or novel, it leaves the audience unable to sleep at night, unsettled even in the security of their own home.

The 2017 IT movie makes use of the jump scare, whereas something like The Telltale Heart employs an exponentially-growing fear that lingers even after the last page.

Other conventions of Gothic fiction include:

- Medieval or ancient settings (castles, old churches, ancient barrows, etc.)

- An emotional response (the lingering fear brought on by what Edmund Burke describes as the Sublime)

- Political or sociopolitical undertones (The Mask of Anarchy by Percy Shelley pairs Gothic themes with a plea for nonviolent resistance)

Putting the Science in Goth Science Fiction

While the occult and the supernatural play a large part in defining traditional Gothic fiction, the addition of science takes the genre to new heights.

Take Frankenstein, for example. Most of what makes the story compelling is the deep moral quandary and tragedy of Victor Frankenstein, brought on by his dabbling in arcane sciences, namely the reanimation of dead tissue. Shelley’s use of science in Frankenstein is a vehicle for plot progression, and largely a catalyst for her character’s ongoing psychosis.

Vampirism is another good example. There are two sides to the same coin.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, brought vampires into the limelight. In a traditional Gothic sense, vampires are creatures of folklore, hearkening back to medieval eras. The story of the 2014 film Dracula Untold follows in Stoker’s footsteps, with the source of horror coming from an ancient creature, presumably Nosferatu. Science has no part in the film.

But, in a Gothic science fiction sense, vampirism might be defined as a genetic or blood disease rather than a result of the supernatural. Renfield Syndrome is the clinical definition we use today to describe an all-encompassing obsession with blood. The condition was named after a character in Stoker’s book.

Using science as an explanation for the occult might seem like a visible deconstruction of the Gothic genre, but in many ways it elevates the elements of horror.

Today, reading Dracula or Frankenstein by itself with no adjacent literature to define them, they seem a bit less scary than they probably were a hundred years ago. They are rooted in a fear of the unexplainable, and use that fear as a vehicle for plot.

This is because modern science and all of its tools are able to help explain some of the phenomena found in traditional Gothic novels (aside from, perhaps, helmets falling from the sky).

The unexplainable is no longer so foreign anymore, is it? Vampirism isn’t the result of an arcane horror, but rather a disease we can define in clear terms. Apparitions can be explained as unique phenomena based on environment, atmospheric conditions, etc. etc.

Taking this Scully-ish approach breaks down the key mechanism of Gothic fiction which is the fear of the unknown. So how do we keep a genre alive when its kingpin tactic has been jeopardized?

What Makes Gothic Science Fiction?

You might be thinking, ‘Gothic fiction still stands today because people are still scared of the unknown’ and you’d be right. As viewers, we can appreciate the Gothic genre for what it is, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t creeped out by The Castle of Otranto or “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

What I’m proposing is that Gothic science fiction is the evolution of Gothic fiction, that this sci fi subgenre is an adaptation of traditional themes meant to appeal to a modern audience.

As a modern reader, the difference between the 1897 Dracula and the 1954 I Am Legend is that Matheson incorporates the idea of the occult—vampirism—and skews it in a science fiction way. In 2021, where electric light and technology reach even to the deepest corners of our lives, a vampiric pandemic inspires more fear than whatever arcane horror might be lurking in ruined castles.

The potential for a widespread blood-sucking, zombifying disease seems a lot more plausible than stuff of folklore because it preys on our fear of the scientific unknown. By that I mean that for those of us that lack the scientific literacy to explain a vampiric disease, it serves the same purpose as any other mysterious Gothic fears we don’t understand.

The core tenant of Gothic fiction is the unexplainable, but our definition of the unexplainable has changed from 200-hundred years ago. And that’s where science comes into play, because the vast majority of us can’t explain how vampiric diseases, the fabric of reality, or extraterrestrial phenomena work. For the viewer, the new unexplainable is on the fringes of science.

In Conclusion

I guess something that occurred to me while writing this is that Gothic science fiction doesn’t seem to have a linear timeline. There isn’t a “this was the first book ever written and here’s the most recent”. It’s a theme that can be transposed on many works, even if they were written a hundred years apart.

At the end of the day, what Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde started, modern science fiction authors modify to keep up with the pace of technological and scientific advancement.

Everyday the bounds of the unknown get pushed farther back, and the Sublime morphs to account for the forward march of science.

As one of the prominent sci fi subgenres, Gothic science fiction continues the tradition of putting into words what we think about at the darkest hour of night.

NFT Digital Art Is a Currency Right Out of Science Fiction

Right now, there’s a lot of talk about NFTs, non-fungible tokens, and NFT digital art; they’ve kind of taken the world by storm.

As someone who is mildly up-to-date in the cryptocurrency scene, the popularity of NFTs came as a bit of a surprise. And it sparked my imagination, too. Watching pieces of digital art being sold at exorbitant prices for clout made me think about the future of our currencies, physical and digital.

Before money, barter and trade was the primary means for getting the goods you needed to survive. A bushel of apples for a flank of meat. It was simple, and a system soon appeared, where certain items would be valued higher than others, based on abundance, time and labor investment, etc.

I originally thought that NFTs might be a futuristic barter and trade system years from now, if we ever came to a global currency fallout. But I soon realized that possibility wasn’t feasible for NFTs in their current state, and I’ll explain why.

But first, let’s break down how NFTs and NFT digital art works.

How Do NFTs Work?

An NFT is a digital asset that operates on blockchain technology, the same infrastructure used for cryptocurrencies.

Many creators create digital art and sell them as NFTs. There are all kinds of NFTs on marketplaces like OpenSea: graphic design art, music, trading cards, video game skins, etc.

As I mentioned, NFTs are non-fungible tokens, which essentially means that one NFT is not equal to another.

A fungible currency is where a single amount is exactly the same as another amount. Like a $1 bill. It’s $1, and no matter how many times you trade that $1 bill for other $1 bills, you’ll always have $1.

Cryptocurrencies are fungible tokens. A single Bitcoin is the same price as any other single Bitcoin.

NFTs are different because they cannot be exchanged for other NFTs. Each NFT has a unique digital signature, making it a one-of-a-kind asset.

Is There Money in NFT Digital Art?

The idea of the NFT baffled me when I first learned about it, and to be honest, it still does. Why would people pay exorbitant amounts of cryptocurrency to buy a piece of art, like a song or a collage, when they could view that art online for free?

Well, the blockchain NFTs are built on provides a traceable ID and transaction history, which essentially means when you buy an NFT, you obtain ownership of it. As opposed to paying a streaming service like Spotify, which you a license to listen to music, buying music as an NFT solidifies you as the owner of it.

Like if you were to buy a famous painting at an auction, but gone digital.

Initially, this practice seemed like nothing more than a flex, a show of wealth. After all, NFTs aren’t tradeable, meaning you either own it for life, or have to find someone willing to pay you for it, sometimes less than what you got it for.

So how is it the NFT market is so big, and yet, seemingly have no clear purpose? Apparently, NFT trading is quickly becoming a popular means of making money, and creators are benefiting.

NFTs, the New, Dystopian Currency?

The concept of NFTs has been around since about 2014, but it experienced a large uptick in popularity in 2021. People are trading NFTs—buying highly sought-after pieces and reselling them at a premium.

The problem with NFT digital art trading, though, is that it’s not driven by any economic principles. It’s purely market-dependent. So, if you spent $2.9 million on an NFT of Jack Dorsey’s first tweet, you better hope someone out there wants it more than you do, or you’re down $3 mil.

But creators are reaping the benefits of NFT trading.

Every time an NFT they created is sold, they receive a kickback from that sale. So if a gif they made as an NFT gets traded around multiple times, they’ll make a percentage of that on top of however much they sold it for in the first place.

No one knows how long NFT trading will be around – the demand for them might die out in a few months, or they could become the future of traceable, authenticated currency.

When I think of a dystopian, cyberpunk worlds, I usually think of cityscapes ruled by tech moguls. The industrialists that sell the tech the world is built on, getting filthy rich at everyone’s expense.

But with a few modifications to the NFT idea, it could become the barter and trade currency of the future. And the richest people of all would be the artists.

How to Make NFTs a Viable Currency

For NFTs to be a viable currency of the future, they’d have to be able to be traded for other NFTs. Smaller NFT tokens could be used for goods or services, and then could be traded on a digital marketplace for more expensive NFTs.

A good example of this concept in action is the Counterstrike: Global Offensive marketplace on Steam. CS:GO is a first person shooter, originating back in the 1990s and early 2000s. In-game weapon skins have a real-life value, a dollar amount.

You can buy skins online directly from the Steam marketplace, and they often retain their value or increase in price as they become more desirable. You can trade skins with other players, increase the value of your skins by adding expensive in-game stickers, trade lesser-grade skins for more high-quality ones, etc. etc.

If NFTs operated like the existing CS:GO marketplace, then they would become much more viable as a currency. Just like the bushel of apples for a flank of steak example, a handful of smaller NFT tokens for a more valuable, larger token. You could trade a small gif NFT for apples, and a Snoop Dogg album NFT for a flank of meat.

It’s a really weird concept, that art could essentially become the lifeblood of a society. Because people always say, ‘oh, the art and culture are what makes a society great’ but in this case, art is literally the means of survival.

Problems with NFTs

One of the primary problems with using NFT digital art as currency in the cyperpunk future is the environmental impact.

Most NFTs run on the Ethereum or Bitcoin blockchain, and those cryptocurrencies use a lot of power. So much so that cryptocurrencies are causing a serious problem for the environment.

A recent report from CNBC found that Bitcoin mining creates 35.95 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year. More than half of the world’s cryptocurrency mining takes place in China, a country that still largely uses coal as a source of electricity.

Bitcoin uses about 707 kWh of electricity, whereas Ethereum uses about 62 kWh. And the output of emissions from Ethereum mining should decrease with the implementation of Ethereum 2.0, which will decrease power consumption to about 1/10,000th of the current rate.

The widespread use of NFTs or crypto on a societal level would be catastrophic for the environment. Without significant improvements to the blockchain and hardware technology, digital currencies could bring about a dystopian future. And not the cool kind, either (pun intended).

For now, NFTs stand as a neat method for digital art, and if you’re lucky, some profit too. But there needs to be significant change for it to become a popular, futuristic barter and trade.

Latest Science News: Larger Brains, More Intelligent? Not the Case

One of the most prevalent conventions of human thought is “Bigger is Better”, whether that’s referring to buildings, cars, bank accounts, etc.

And the same concept applied to brains, too. For a long time it was thought, the bigger the brain, the more intelligent the creature.

But, new studies show that the correlation between brain size and intelligence isn’t really much of a correlation at all, and the age-old idea that increased size = increased [insert variable here] has been blown out of the water.

A team of 22 international experts in human and animal biology have studied approximately 1,400 brains of extinct mammals. The idea was to compare information about their brain masses with the rest of the body in each sample.

Latest Science News Says: Big Brains Aren’t Big Enough

All this biology news looks like science fiction, but it is not. The study, published in April 2021 in Science Advances, is the result of years of research on brain size and intelligence.

The species known to be the smartest on our planet have very different proportions:

- Elephants amaze us with their size, but their brain development is much greater

- Dolphins tend to shrink their body size over the years and mutations across the species, but the brain grows larger with each generation

- Monkeys have a wide range of sizes and seem to follow a pattern when it comes to body and brain

- Humanity follows a trend similar to dolphins, where we become smaller and with greater intellect.

Kamran Safi, a lead researcher from Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, said that “Using relative brain size as a proxy for cognitive capacity must be set against an animal’s evolutionary history and the nuances in the way the brain and body have changed over the tree of life.”

Studying the Past

The researchers discovered that the biggest evolutionary changes to brain size occurred after cataclysmic events in the earth’s history. Think events like meteor strikes and massive climate shifts.

The first point analyzed was the mass extinction 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretatian era. During this period, dramatic changes were found in rodents, bats, carnivores, and some animals recognized as direct survivors of dinosaurs.

Likewise, between 23 to 33 million years ago, at the end of the Paleonege era, profound changes in the structure of seals, bears, whales, and other primates were also found due to a brutal change in the planet’s climate.

Based on this information, who’s to say that other events in the future won’t spark evolutionary changes too? Like the eruption of a supervolcano or widespread nuclear fallout.

Humans Cognition and Their Developed Brains

Talking about evolution concerning our own species in this aspect needs the support that the research from the University of Vienna carried out in 2015.

After more than 8,000 individuals were studied nearly 90 times, the result says that it is not the size but the structure of our brain that gives us greater intelligence.

Although the result is not 100% compatible because they have tested IQs, it is accepted that what makes someone more or less intelligent than others is their ability to rationally understand the world around them, their memory, resolutions, and logical capacity.

Another project, published in the Royal Society Open Science in 2016, supports the thesis that brain stucture, not size, is indicative of intelligence.

An experiment used to test brain function has subjects collect food in a container that has two entrances. Once the specimen learns both entrances, a transparent block is added, and if it remembers the alternate path to the food and does so, it is considered to be more intelligent than another species that insists on the shortest path.

Many of the test subjects (which varied in size and species) demonstrated the same performance, which again shows subjects with different brain sizes are capable of reaching the same end goal. It’s all about structure.

All of this research leads to the question: have humans evolved to unlock the full potential of our brains? Or will cataclysmic events in the future lead to evolutionary changes in the human brain?

It also raises the question: what does this new science mean for non-earth species?

Alien Science Meets Earth Science

A common stereotype about aliens is that their hyper-intelligence comes from their massive brains, which is reflected in the oblong-shaped heads.

But, if alien biology follows the new developments in Earth biology, it’d be more likely that aliens have slighter frames and smaller heads. It’s all about brain structure, not size, so the massive heads common in depictions of the green men don’t seem as realistic.

What do you think? Have cataclysmic events altered evolutionary patterns for non-Earth lifeforms, just like they have influenced human and animal brain size/structure? And what’s next for the human evolutionary pattern? Let us know in the comments!

Lightning is the Coolest Way to Decrease Greenhouse Gas

We have seen many different ways to prevent and reduce greenhouse gas, such as recycling, using sustainable energy, switching to electric cars and even changing our diets.

And although we have our sustainable ways, somehow, nature always has its own ways of beating us to the point, in almost every aspect.

Maybe you’ve already heard about its capacity to regenerate the ozone layer, which is a cool enough fact, but in this article, we’re going to talk about how lightning bolts can decrease greenhouse gas.

The Nature of Lightning

Lightning bolts have sparked (pun intended) a lot of myths and legends over the years. Thor, Zeus, the thunderbird, etc. Overall, lightning bolts are usually associated with ethereal beings, and were a thing of mystery.

But, as science progressed, we made progress decoding what lightning actually is. For starters, Ben Franklin flew his kite with a pointed wire attached to the apex near a thunderstorm. Although it was a very dangerous experiment, it helped us discover electricity and how it can be conducted.

Fast forward to present day, William H. Brune, a meteorology professor at Penn State University, attached an instrument to a plane flying from Colorado to Oklahoma during a thunderstorm to study lightning. What did it prove? Well, it showed that lightning is beneficial to the health of the atmosphere.

Initially, Brune thought something was wrong with the instrument, since it was receiving a massive amount of signals found in the clouds. So he removed the signals from the dataset and shelved them for over 5 years, planning to study them later.

A few years ago, he took out the data and with the help of an undergraduate intern and a research associate, they realized that the signals received were actually chemical radicals such as hydroxyl (OH) and hydroperoxyl (OH2), and then linked these signals to lightning measurements made from the ground.

And that’s where it gets weird.

Cleaning with Lightning

Lightning occurs when the heavy mix of warm clouds and cold clouds meet. Water droplets in warm clouds collide and “rub” against frozen particles present in cold clouds, forming an electric discharge. This linear discharge can descend to the earth, as lightning, or remain in the clouds, often called heat lightning.

That was basically the information we had until now. Today, we know that this electric discharge is responsible for producing nitric oxide (NO) due to its rapid ‘hot n’ cold’ activity.

When combined with the oxygen of the atmosphere, it creates nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which later on decomposes into hydroxyl radicals (HO2) and ozone (O3) in sunlight. A strange, yet unique form of cleaning out air pollution.

So to sum up this chemical dilemma, each lightning bolt concentrates a heavy amount of air pollutants in their electric discharges, so that they can be released and later on transformed into air oxidizers.

Lightning, Greenhouse Gas, and Climate Change

Okay, maybe lightning itself isn’t the pancrea for global warming, but it’s definitely working against it.

Most greenhouses gasses are created naturally and have been around since the beginning of time. However, fluorinated gasses are what we should worry about, which are all gasses that are synthetic, byproducts of humanity. These gasses create a layer of heat in the atmosphere called the greenhouse effect. This greenhouse effect is what leads to global warming. Here are some of the greenhouse gas components:

- Carbon dioxide

- Methane

- Water vapor

- Nitrous oxide

Some studies point out that climate change directly affects the frequency and rate of lightning bolts. Global warming has shown to increase the activity of thunderstorms, producing more potent and more frequent lightning.

Is nature somehow trying to “alleviate” itself or even defend itself from a massive atmospheric breakdown?

Hydroxyl radicals and ozone are primary oxidation components that help clean the atmosphere and eliminate greenhouse gases. And as we now know, lightning creates these radicals.

While lightning won’t solve all of our global warming problems, perhaps this discovery will lend itself to other ways to decrease greenhouse gasses.

Lightning factories like in Legend of Korra? Creating raw electricity with renewable energy? Imagine finding a way to shoot bolts of lightning into the atmosphere, powered by wind and solar power.

How else could the lightning discovery help us combat global warming? Let us know in the comments!

Interested in other interesting science news? Check out our blogs about intestinal breathing apparatuses and atomic bomb testing sites!

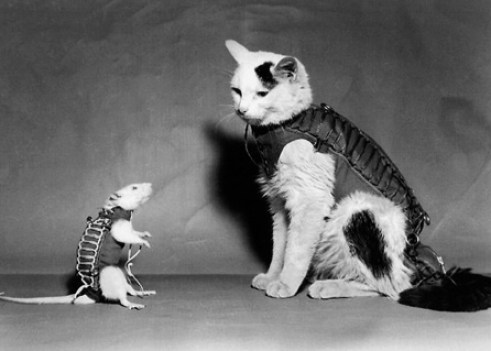

The History, and Future, of Animal Testing in Space

The pages of space travel history are filled with records of countless animals and insects who were sent into space.

Perhaps the most famous was Laika, the cosmonaut dog sent into orbit on Sputnik 2 in 1957. She became the first animal to ever enter space, and her journey sparked a flurry of other tests that eventually led to the first human space trip in 1961.

But, why do scientists send animals into space, anyways? And what do recent medical discoveries like intestinal liquid ventilation mean for the future of space travel?

Why Perform Animal Testing in Space?

Animal testing has polarized the science community. On one side, the human safety activists argue that animal testing helps protect us from harmful side effects of pharmaceuticals, cleaning supplies, and pretty much every other product under the sun.

On the other side of the spectrum, the animal rights activists argue that there are other ways to safely perform tests that doesn’t cost lab animals their lives.

There are valid points on both sides of the argument, but sending animals to space has sort of become the posterchild for both animal testing and abolishing animal testing.

So why do we send dogs, chimps, and spiders to space to begin with?

In the early days of the space race, scientists were uncertain about the conditions in space. There were a lot of unanswered questions:

- Could humans survive the g-force of entry and reentry?

- Would the human body withstand the stress of a prolonged space trip?

- How would the body readjust to Earth’s gravity?

Bioastronautics specialists figured that the road to these answers was simply to send various creatures into orbit and observe the results. Unfortunately, almost all animals sent into space died from the stress. But their sacrifice led to the first human spacewalk, the first feet on the moon, and the development of the ISS.

What Kind of Creatures Got Tickets to Space?

While Laika was the first dog in space, she was followed by:

- 32 monkeys and apes (Ham was the first chimp in space)

- Small mammals like dogs, cats, guinea pigs, and rabbits (Félicette was the first cat in space)

- Mice and rats

- Frogs, turtles, newts, and geckos

- Insects and arachnids (ants, fruit flies, orb spiders, etc.)

Photo from thenewstack.io

While no adult birds were brought to space, the American flight Discovery STS-29 took 32 chicken embryos into space.

Once scientists had a substantial amount of data about the effects of space on the body, they became interested in unborn creatures.

In addition to the countless live animals sent into orbit, scientists have sent quail and frog eggs into space, as well as the seeds for potatoes, cottonseed, and rapeseed.

But new studies have shown that certain animals have the capacity to breathe with much lower levels of oxygen than previously observed, which is obviously a plus when it comes to space travel.

Discovery of Intestine Breathing in Pigs and Rodents

A new study published in the medical journal Med presents the findings of how oxygenated liquid given to the intestines supported two mammals in respiratory failure.

Both pigs and mice were able to survive environments with critically-low oxygen levels because of oxygen tubes inserted through their rectums to reach the intestines.

Kind of absurd, right?

Well, scientists have known about non-lung respiratory functions for a while. Sea cucumbers and some freshwater catfish, for example, use their intestines to process oxygen. But until now, no mammals have been known to possess such abilities.

What does intestinal breathing in these mammals mean for humans? And what does it mean for the future of animal testing in space?

Medical Benefits of Non-Lung Breathing

The researchers who found the intestinal breathing capabilities of pigs, rats, and mice stated that the discovery might be used in the future to help human patients in respiratory failure.

75% of mice that were given the intestinal liquid ventilation system survived for almost an hour in oxygen-deficient environments, and in non-lethal oxygen-deficient environments, mice with the intestinal liquid ventilation were more active than mice without.

It’s still unclear whether or not humans have the same intestinal breathing abilities, but Takanori Takebe, head researcher of the project, said that “The level of arterial oxygenation provided by our ventilation system, if scaled for human application, is likely sufficient to treat patients with severe respiratory failure, potentially providing life-saving oxygenation.”

In the current medical climate, such a device might remedy the lack of ventilators for COVID-19 patients.

Thinking Outside the Box

As science fiction enthusiasts, we like to take real-world discoveries and bend them a little. In this case, the finding of intestinal breathing sparks questions about a functional use for it in the vacuum of space (or at least, in a space station).

Picture this: you’re on a spaceship in deep space, life support systems are failing and your friend is badly wounded. Oxygen is a precious commodity and you’re already running low. You have to keep your friend alive until backup arrives.

The intestinal liquid ventilation system can support your friend’s respiratory function while not consuming valuable oxygen gas. You’re able to keep him stable until rescue arrives.

While not the most realistic scenario, it’s perfectly feasible that in the future, intestinal liquid ventilation will be used to life-saving effect, not just on Earth, but in space too.

And who knows, maybe pigs and mice will be sent into orbit to test the ILV system before it’s approved for human use. While many of the animals sent to space lost their lives, their sacrifice made modern space exploration possible, and will continue to advance our trek beyond Earth.