We made it! Christmas Day has come and gone here in the States, and as the Holiday season wraps up, we wondered: how did people around the world spend their holidays?

And because we’re a speculative blog, that question in turn led us to wondering: how did people not on this world spend their holidays?!

So, a-searchin’ for answers we went, and we found some fun facts about how Christmas is celebrated in Outer Space …

Category: Sci-Fi Classics

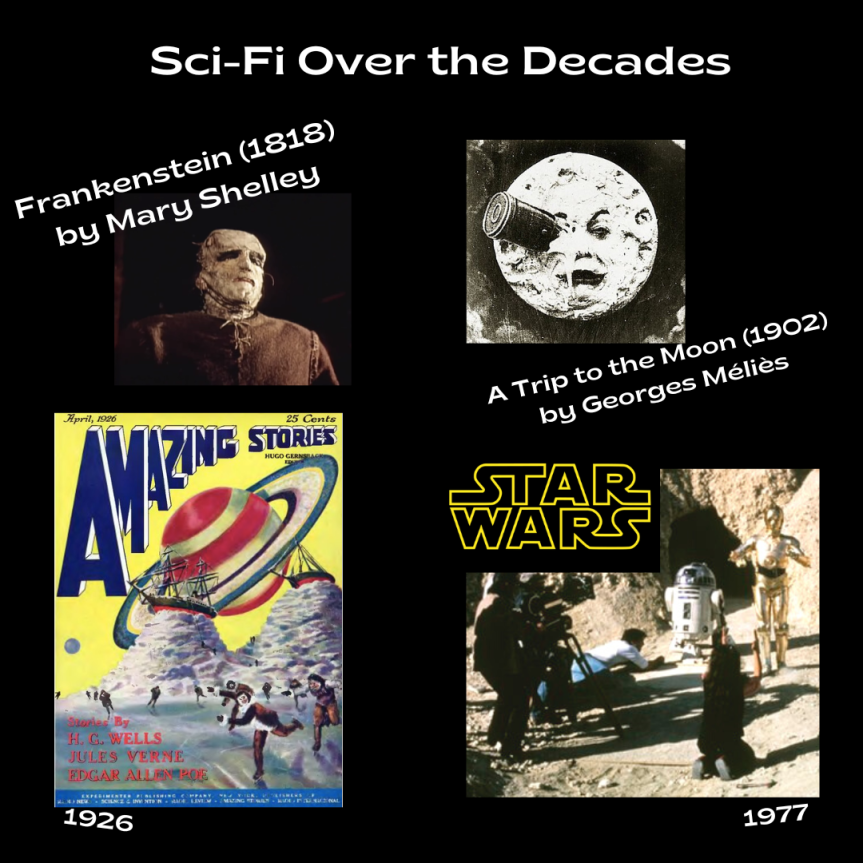

Science Fiction: The Evolution of a Genre

Science fiction as a genre has evolved and expanded over the decades, inviting innovative ideas from forward-thinking minds. Avid fans of the genre and its subgenres (some say there are over 30 subgenres!) probably can’t recall a time before there was an entire section in bookstores or online shopping platforms dedicated to science fiction. The genre is not the oldest (poetry claims that distinction) and its evolution is a stunning example of what human ingenuity can accomplish through a combination of imagination and a foundation of science.

Earliest Records of Science Fiction

Unsurprisingly, fiction aficionados do not quite agree on when Sci-Fi as a genre began. Many posit that it was during the 2nd century when Lucian of Samosata penned A True Story, the book that astounded readers with its descriptions of aliens, travel beyond earth, and war among the planets. Several genres in addition to science fiction have attempted to lay claim to this work and its accolades as belonging within their genre. This book, and many others up through the 13th century, do seem to contain themes and elements of Sci-Fi but do they have enough to qualify them fully? The debate continues…

Let’s look at the opinion of astronomer and scientist Carl Sagan. His belief was Somnium by Johannes Kepler is the first true Sci-Fi book. He may be right. After all, within those ancient pages the author describes what it could be like to view Earth from a vantage point on the Moon long before Neil Armstrong set foot upon its regolith-covered surface. Other early contenders include a personal favorite, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as well as Jules Verne’s epic Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. With a genre whose stories are so rich with possibility and so embracing of the unknown it stands to reason that each of these and many more have directly impacted, shaped, and built the incredible genre that we know and love today.

How Sci-Fi Has Changed

The 1900s saw a huge push toward defining the genre and introducing stellar, new concepts to readers of literature. When Hugo Gernsback published the first American Sci-Fi magazine in 1926 called Amazing Stories, he unwittingly started a further boom for the genre as he put incredible works of fiction and art in the hands of thousands of people each month. One author in particular, E. E. Doc Smith with Lee Hawkins, is credited for writing the first notable space opera, The Skylark of Space, which was put in the magazine. A comic strip celebrating Sci-Fi was also born from the magazine as Philip Francis Nowlan introduced the nation to Buck Rogers with Armageddon 2419. Just over a decade later in 1937 a new editor took over a competing science fiction magazine called Astounding Science Fiction and ushered in what fans call the “Golden Age of Science Fiction.” Editor John Campbell focused on content that centered on real, scientific progress and advancements in technology. As a result, the genre blossomed as readers were both in awe of the advancements of the day as well as excited by the fictional elements of each story.

In the 1940s a Hugo Award was given to author Isaac Asimov for his book series entitled Foundation. The story presented the idea of galactic empires, a novel concept in the day. Throughout the 1950s Americans stayed riveted to new ideas including interstellar communities, human evolution of the future, military science fiction, and much more. The 1960s and 1970s saw further advancements in technology, prompting authors to write about themes that stretched the limits of our understanding at that time. Things like human psychology, physical and mental abilities of the human body and mind, and questions about concepts such as gender, feminism, and social constructs played into stories heavily during this time.

Films’ Influence

The onset of film opened an entirely new way for humans to see and interpret the world around them. One of the earliest known recordings that could be labeled as science fiction is the iconic silent film A Trip to the Moon directed by Georges Méliès in 1902. It was shot with a meager budget of 10,000 francs and was only 9 minutes long. A recent film entitled Hugo tells the true-to-life tale of the director and offers a glimpse into his creative mind. By 1927 a full-length science fiction film called Metropolis failed at the box office but has succeeded in the eyes of modern filmmakers for its innovative science fiction concepts. Fast forward to 1968 when 2001: A Space Odyssey and the original Planet of the Apes both came out and it’s easy to see how Sci-Fi enjoyed a burst of popularity as it garnered new fans while enchanting fans of old. The door was wide open for another quality, successful film when in 1977 George Lucas released what we know today as Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope. This, of course, sparked a global obsession with the series and expanded the reach of science fiction.

Science Fiction Today

From its humble beginnings, the genre has risen to include some of the bigger blockbuster hits in Hollywood and some of the more heavily read books in the nation. As writers and authors continue to push the limits and expand human awareness of what could exist beyond what we can see and experience today, readers are spoiled with a plethora of media options that range from classic to modern and encompass a variety of subgenres. Let us not forget, however, that once upon a time, not too long ago, a few brave writers put pen to paper and dreamed up worlds that no one had dared to capture in ink.

Will Near Future Sci Fi Lose Its Luster?

Recently, I’ve been reading Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, and I was struck by how old it seems. For me, at least, the true measure of an older science fiction novel is if it manages to maintain a certain level of credibility within the logical timeline I have running in my head.

Like, I read Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany, and yeah, it was published 60 years ago, but it never succeeds in placing itself anywhere in a coherent time or space I’m familiar with. There’s no bending of history to accommodate this novella, everything Delany writes could have happened, or still could happen in the future.

But with books like Childhood’s End, I can’t help but think about how it’s lost that security of time and special awareness. The book, published in 1953, starts out with US and Russian engineers in a race to put a military spacecraft into orbit. The way Clarke spins this, he makes it seem like it’s a big deal. The first craft in space! And he probably succeeded in hyping up his audience in 1953, because at that time the US and the USSR were in the middle of their Cold War rivalries.

As readers in 2022, however, we know that in 1957, Sputnik becomes the first space satellite to orbit the Earth. When Clarke’s timeline in Childhood’s End jumps forward, we present-day readers have to suspend our beliefs in order to keep going.

Dispelling any knowledge of the future as we know it after 1953 is sort of the antithesis of Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. We have to erase our minds and our beliefs to read Childhood’s End as a science fiction novel, not as an outdated alternate history.

And it got me thinking about near future sci fi books in general. In how many years will we look back at science fiction books and movies that speculated on our near future and say “nah, that’s just not it”?

Or, will we engage in the active purging of our memories when reading these books to accommodate the timeline and scenarios that may have already come to pass, whether true or not?

How Near Is the Near Future?

Obviously, science fiction spans across multiple different subgenres and niches, some of which specialize in far future scenarios, thousands of years after humanity will be dead and gone. Others hit closer to home, waxing clairvoyant about ten, twenty, or fifty years into the future.

Some sci fi concept novels or movies make a point of clearly specifying a time and place of the story, so much so that the time has become part of the story’s identity.

Blade Runner: 2049, for example, or even Cyberpunk 2077. These works make the time in which they’re situated part of the premise. Just thinking about the future will get people to consider these works as the blueprints for the years 2049 or 2077.

Other works get even closer to our current time in space. The Martian predicts colonization efforts on Mars by 2035, while Constance brings human cloning to the forefront in 2030.

As these authors get closer and closer to our present day, the likelihood of their speculations coming to fruition gets smaller and smaller.

Near future sci fi books act as a kind of playful challenge to the science community. “Do you think you can perfect human cloning and commercialize it by 2030? I bet you can’t.”

But here we have to dive a bit deeper, look directly into the face of the question: what’s the purpose of near future sci fi, anyways?

The Art of False Predictions

Cory Doctorow talks about how sci fi authors predict the future in an essay that was published as part the Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds. An excerpt was published on Slate.com, where he notes that:

“When it comes to predicting the future, science-fiction writers are Texas marksmen: They fire a shotgun into the side of a barn, draw a target around the place where the pellets hit, and proclaim their deadly accuracy to anyone who’ll listen.”

And he’s right. Sometimes a sci fi author will get wildly lucky and hit the nail on the head, winning the million-dollar prize and fame forever.

But most times, predicted, imagined futures will pass us by every day without any grand hoorah, ending up in a catalogue of unfulfilled timelines.

And then there’s the in between-realm. The few science fiction legends who had enough common sense and foresight to predict what our future would be like in the next 50 to 100 years. Arthur C. Clarke predicted 3D printing, Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick predicted something like the internet that would connect the whole world.

But, here’s the fun part. These guys, they’re still shooting that double-barrel shotgun from the hip with a Sharpie in their teeth.

It’s easy to make a broad speculation about the future based on events in the past and the current state of science.

For the Golden Age sci fi writers, looking back at the technology of their childhood, and then looking at the world they were living in, it must have been fairly easy to assume what was coming next. Radio, telephones, television—those things were shaping the world in sci fi’s heyday. To look forward and think about a more advanced transfer of information from person to person, a method that’s faster, is only natural.

Does that mean Clarke, Asimov, and Dick predicted Facebook? Absolutely not.

And I think that’s where we find the answer to our titular question: Will near future sci fi books lose their luster?

The Devil’s In The Details

The reason I started thinking about this question of longevity of sci fi books is because Childhood’s End made me recondition my knowledge of history to read it without skepticism. The future for Clarke is distant history for me.

And I assume people in the year 2060 will look back at Blade Runner: 2049 and laugh, knowing that their lives are either much better or much worse than they were imagined to be back in 2017.

Films and books like that, in this regard, made the mistake of being too specific. The first rule of sci fi predictions is to never timestamp anything. Had the film been named Blade Runner 2, perhaps people might have been able to extend the possibility of a near future where Replicants and Blade Runners walk the streets.

The Golden Age crew thought up something like the Internet, but they didn’t specify when it would be created, who was going to do it, what it would be called, etc. So, in many ways, they were right.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that near future science fiction books will always make predictions about a time and place and a technology. When we come across a book like Childhood’s End where we as the reader are required to willfully ignore recent history for the sake of the story, just know that that author fell prey to the camp of specificity.

And we can’t wholly discount these once-could-have-been-futures, either. In 2060, we’ll probably look back at The Martian, Constance, Blade Runner, all of them and take something from them. It won’t be a slice of science history, rather a note about the human experience, something we can relate to even though we might be living in a world none of our sci fi authors could have imagined.

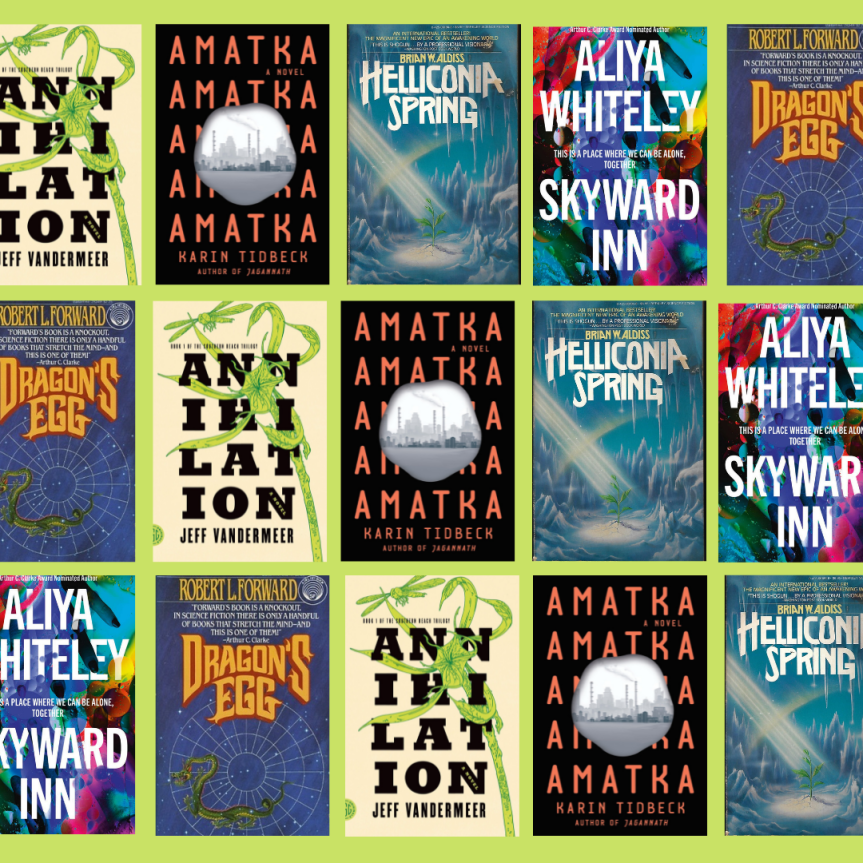

Top 5 Sci Fi Books with Weird Landscapes

It’s been a while since we discussed any Top 5 Sci Fi Books on Signals from the Edge, so I figured it’s high-time we do.

I wanted to take a look at some of the weirdest landscapes throughout science fiction. These include neutron stars, landscape structures dictated by vocal ques, and sentient slime beings in deep towers.

Here are the top five sci fi books with weird landscapes!

Know of a weirder book? Leave a comment below to tell us about it!

Skyward Inn by Aliya Whiteley

Aliya Whitelely has a track record of making weird, uncomfortable fiction. Her novella The Beauty was my first introduction to her work, but Skyward Inn was certainly more unsettling.

In this novel, we have two different weird landscapes that are connected to one another. We have the Earth as we know it (well, kind of), and we have the planet Qita, which has been conquered by Earth.

Both of these landscapes are connected, to the point where what happens on Qita, happens on Earth. At one point in the novel, Earth’s land starts to turn to mud, and then slime, and then a flood sweeps all of the inhabitants up into a central location—the Skyward Inn. But not only is the land itself turning to sludge, so are the people.

Like we said, everything is connected, the planets, the people, the land. Skyward Inn is certainly a slow-burner, but it’s one of the most disturbing sci fi books I’ve read.

The Helliconia Trilogy by Brian Aldiss

As far as weird landscapes go, Brian Aldiss certainly hit the nail on the head with his Helliconia Trilogy. Published in between 1982 and 1985, Helliconia Spring, Summer, and Winter all take place on the planet of Helliconia, an Earth-like planet in the Batalix-Freyr system.

The series doesn’t really follow a certain main character because the timeline spans across thousands of years. Instead, the books focus on the evolution of civilization on Helliconia, a planet that’s similar to Earth enough to support life, but different enough to make it incredibly difficult.

For example, seasons on Helliconia last for hundreds of years, with winters being equivalent to Earth’s Ice Age, and summers being scorching hot. Accompanying the seasonal differences are some new diseases, such as bone fever and fat death, both of which are viral eating disorders.

All-in-all, the Helliconia Trilogy isn’t nearly as weird as Skyward Inn, but it certainly gives a lot more backstory and scientific information about life on this non-Earth planet to make it bizarre.

Dragon’s Egg by Robert L. Forward

Dragon’s Egg is one of those old sci fi novels that stands out because of its weird premise. Published in 1980 by Ballantine Books, Dragon’s Egg focuses on the development of the Cheela society, a group of incredibly tiny people that live on the surface of a neutron star.

If that’s not a weird landscape, I don’t know what is! The whole environment of the novel is other-worldly. The Cheela inhabit the neutron star, as mentioned, and when humans eventually show up to explore their home, the rapidly out-develop the humans in terms of technology.

Time on the Dragon’s Egg, as the neutron star is called, moves much more quickly for the Cheela, where 30 human seconds is one Cheela year.

This book is a pretty fun read if you can get over the dense, scientific worldbuilding.

Amatka by Karin Tidbeck

There are a few things that make the landscape of Amatka weird. First, it’s just eerie. Lakes freeze and thaw without the interaction of weather, and most of the population live on underground mushroom farms.

But what really makes the landscape of this novel weird are the rules around it. Everything in the colony of Amatka must be named vocally, from farm machinery to buildings in town, else they become “gloop”.

And stuff really starts to kick off when more and more things start turning to sludge, and the conspiracies that government has been indoctrinating their people with poke through the surface.

Amatka was originally published in Sweden in 2012, and was translated to English in 2017. It stands as one of the most politically-charged and weird sci fi pieces out there to date.

Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer

Let’s be honest, no list of weird science fiction worlds would be complete without something by Jeff VanderMeer. He’s often regarded as one of the most prolific writers in the New Weird movement, where his fiction continuously crosses back and forth over the horror, science fiction, and fantasy borders.

I recently read Annihilation for the first time, the first book in the South Reach Trilogy, and inspiration for the 2018 film with Natalie Portman.

The landscape of Area X in the novel is one of the weirdest places that I’ve encountered in my reading of science fiction. The contrast between the Lighthouse and the Tower, diametrically opposed pinnacles, set an unsettling vibe over the whole book. Not to mention that dolphins with human eyes, moss-covered human statues, sentient slimes, and creatures molting human skin.

Annihilation is as weird as it is profound, and it’s one of the most thoughtful books I’ve read in a while.

Does Paris Syndrome Have a Place In Speculative Fiction?

Paris Syndrome is one of those things that everyone’s heard about but most people haven’t experienced. It’s a result of high expectations of a place, primarily Paris, hence the name, and the resulting disappointment when the place doesn’t live up to the hype.

It seems like a very specific condition, and it is, and in this article, I want to dissect how Paris Syndrome plays a part in science fiction, or, how it might.

What is Paris Syndrome?

For centuries, Paris has been a travel destination for people from all over the world, from all walks of life. The city has a rich history of intrigue and romance, and often, the hype around the city is far more exaggerated than what the city has to offer.

Paris Syndrome was coined by Japanese psychiatrist Hiroaki Ota when he worked at the Sainte-Anne Hospital Center in France. The condition, as Ota states, is primarily seen in Japanese tourists who visit Paris. The high expectations set by magazines, media, and travel advertisements—like how people think Paris is filled with models, millionaires, and artists—are the primary cause of Paris Syndrome.

It’s worth noting that the condition comes in two forms—the people that had predetermined mental conditions that were triggered by the realization that Paris isn’t a city of glamour and romance, and those people that had no prior history of mental conditions.

Those who suffer from Paris Syndrome often display delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, and in severe cases, derealization and depersonalization. Not to mention the psychosomatic effects, like dizziness, sweating, trouble breathing, and vomiting.

The condition was deemed so serious that the Sainte-Anne Hospital and the Japanese Embassy set up a department to assist Japanese travelers suffering from Paris Syndrome.

How Does Paris Syndrome Apply To Sci Fi?

While the original use of the term Paris Syndrome was to describe Japanese travelers experiencing a place that hadn’t lived up to their expectations, it can also be used to describe the same situation in different cities, regions, countries, etc.

When I was reading about Paris Syndrome, even just the simple article I’d found, a thought crossed my mind. How severe would Paris Syndrome be in the future? For a time-traveler, maybe, or for someone so sheltered from society that they experience the extreme effects of Paris Syndrome.

Imagine a character who had been living in a rural area far removed from a cyberpunk city in the future, that all of their perceptions of the place were from advertisements, news, or second-hand accounts. Now imagine they visit the city and are so overwhelmed by its neon bulbs, drugs, crime, and all-around nastiness that they start to have hallucinations and delusions. To me, at least, it sounds reasonable.

Even traveling from a small, Pennsylvanian town to NYC for the first time, I was anxious, felt closed-in and constantly watched, and generally uncomfortable. What would that experience be like in a sci fi world?

I started looking for examples of Paris Syndrome in science fiction literature, and I uncovered some interesting things.

“Border Control”

The first story I came across was the flash piece, “Border Patrol” by Liam Hogan, published in The Arcanist.

I’m familiar with Hogan’s work from when I worked on the Triangulation anthology series, as he was a regular contributor. His work has always been interesting and thought-provoking, and this story was no different.

In this micro-fiction piece, Hogan thinks about what Paris Syndrome would be like for time travelers. And rightfully so. The future holds so many possibilities, it’s easy to create a grand illusion of what it would be like. But, it’s probably much darker and mundane that we imagine it to be.

I suppose the same would apply to the past. If you traveled back into the past, say, the 1920s, you might expect Gatsby-style parties, car-rides through growing cities, and unprecedented wealth. However, your hopes would be dashed when you landed in the trash-strewn streets of New York, where the average American is still grieving their losses of WWI and struggling to get by.

Speaking of war, let’s get to our next example:

The Forever War

After picking r/sciencefiction’s braintrust, I realized that The Forever War by Joe Haldeman has elements of Paris Syndrome, while not named as such.

For those of you who haven’t read The Forever War, the premise is that the world’s most elite military recruits are sent into space to wage an impossible war with the Taurans. Because of their tech and their missions in the farthest reaches of our galaxy, time passes much more quickly on Earth than it does for the recruits waging war.

When they finally return to Earth, so much time has passed on their home planet that they don’t recognize it at all. And that’s where Paris Syndrome comes in.

Instead of finding their place in the futuristic Earth, they mourn so much for the place that they knew and had dreamt about while at war that they reenlist. They’d much rather return to a galaxy at war than learn to live in a place that so drastically changed shattered their hopes and expectations.

Of course, there are elements of PTSD, but the Paris Syndrome is part of the underlying reason Mandella and Potter return to the Forever War.

Frequently There, Never Named

Even though we might not recognize it, the Paris Syndrome plays a part in many science fiction novels. It’s never noted as being the Paris Syndrome, but the same idea is there.

The Dark Eden series by Chris Beckett has elements of Paris Syndrome, and Aurora by Kim Stanley Robinson and The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin both have shadows of the idea.

Paris Syndrome is more prevalent that we might think, and it’s certainly a condition that plays—or has the potential to play—a larger part in science fiction literature. Like in The Forever War, the future has so much potential that everyone has their expectations of what it will be like. But, when faced with the harsh reality of things, it turns out to be less ideal than one could have hoped.

I think in many ways, we might all feel Paris Syndrome sometimes, though to a less severe degree than Japanese tourists in France’s pearl. If you’ve ever had high hopes for a new book or show or movie, and then felt wildly disappointed or distraught when it doesn’t live up to your expectations—that’s small scale Paris Syndrome. Especially if there was a lot of hype around it, like positive advertisements, reviews, etc.

What do you think? Is it a stretch to believe Paris Syndrome plays a role in science fiction? Or is it a reasonable hypothesis?

Let us know in the comments below!

A Cyberpunk Short Story About Tequila, Candy, & Bar-fights

We usually don’t discuss a singular sci fi short story on Signals from the Edge just because they’re short, and we like to have a lot to talk about.

But that changes today, with a discussion of the cyberpunk short story “The Life Cycle of a Cyber-Bar” by Arthur Liu, published in Issue 12 of Future Science Fiction Digest. From the first few sentences, this story really caught my attention, not just as a quirky, fun story, but as an example of the evolution of cyberpunk as a genre.

Is Cyberpunk Dead?

In the past few weeks, there have been a lot of articles published online about the cyberpunk genre as a whole. Everyone from WIRED to Tor.com has written some kind of piece with their own take, and they pretty much all come to the same conclusion: the traditional cyberpunk genre is either dead or dying, and what’s coming out of the ashes is the new era of cyberpunk.

And for the most part, they’re right. The cyberpunk of forty years ago embodies a time of massive technological growth and rampant capitalistic greed. Computer tech was improving with every passing day, and wealth was amassed by a few as the rest struggled to keep up.

Those things made their way into cyberpunk literature, and paired with a keen sense of existential dread, the genre pinpointed the problems—and future problems—our society was faced with.

To a certain point, those principles still apply today. William Gibson’s warnings about artificial intelligence in Neuromancer are seen coming to fruition with the likes of GPT-3, and tech moguls are using Neal Stephenson’s metaverse ideas as a guidebook to create their own virtual reality societies.

But it begs the question: Where do we go from here? While our modern tech hasn’t quite caught up with that of traditional cyberpunk, we’re seeing more and more aspects of cyberpunk culture in our everyday lives. Fashion, video games, music, and most importantly, ideologies.

The cyberpunk of the 1980s is still relevant, but it’s nearing the end of the line. Soon, our tech will catch up, and we’ll have lived out the predictions of Gibson, Stephenson, and Sterling, and what comes after?

That’s where modern cyberpunk comes in. Enter stage right: “The Life Cycle of a Cyber-Bar”.

Don’t Drink the Tequila

In Arthur Liu’s cyberpunk short story, we see a sentient cyber-bar work toward it’s three great feats. Primary among these feats is to reproduce, which seems weird coming from a seedy bar, but bear with me.

Essentially, everything within the cyber-bar is part of a larger organism. The cups, the tequila, the ice, the floorboards—all of it is connected to the cyber-bar, either as “fluid discharged from the excretory system,” or a “hyperplastic growth”.

By the end of the story, we see the bar reach its goal, manipulating itself into flames where the smoke carries its spores deep into space, where it will travel on spaceships or asteroids to populate a new planet.

How is this cyberpunk? It seems like one of those weird sci fi short stories online that doesn’t fit into a sci fi subgenre.

There you’d be wrong.

The story gradually expands in scope. In the beginning, we see the customary cyberpunk characters enter the bar, the guys “all cast from the same mold: flattop haircut, tough, silent, smelling of cigarettes, with suspicious eyes and heads full of obsolete microchips.” This is an homage to traditional cyberpunk, the likes of Case and Hiro Protagonist.

But then we see the same situation plaid out in the eyes of the bartender, who knows the nature of the cyber-bar. She endures constant nights of bar fights and blood, her body shattered by bullet holes only to be repaired by the nanocells the cyber-bar gifted her. She notes to us readers that she plans on spending her whole life at the bar.

That’s the ideology. The notion that a company or entity will garner your loyalty by providing more than just a paycheck, like a body modification or a cure to an ailment.

And as the story continues, we see the deviation from the traditional cyberpunk themes.

Instead of focusing on hard-pressed, edgy characters with dark pasts and flawed morals, we see a whole new side of the genre: the structures. The cyber-bar is a big part of the genre, whether it’s a popular hang out for the tech-gangsters, or where the protagonist goes to drown their sorrows.

What Makes the Cyber-Bar Special?

Aside from the sentient nature of Liu’s cyber-bar, there’s something underneath all the biological process talk that speaks to the genre as a whole.

The idea that the cyber-bar is a growing, thinking, planning, and evolving creature might be seen as a metaphor for the cyberpunk genre.

We start off with a single cyber-bar, which to an untrained eye resembles any other bar. But, when the bar turns into a candy house and mutates those who consume it, we get a second cyber-bar, directly across the street from the original.

It’s noted that the secondary cyber-bar is a facsimile of the original, which is a commentary on the state of cyberpunk. The themes of the genre are so potent and cliché at this point, that generally, any two works in the cyberpunk genre, when broken down, are the same.

Two bars equate then to two cyberpunk novels (or any medium, really, video games, films, etc.), the same in every way.

And when the cyber-bar finally reaches space, it has ascended (literally). It represents the rebirth of the genre. We move from the dirty streets flooded with neon lights to a new frontier, where sentient cyber-bars are the norm.

Liu’s poignant take on cyberpunk gives me hope for the future of the genre. He’s right that a lot of the current cyberpunk short stories, novels, movies, and games are deep down copies of traditional cyberpunk from years past.

But this new cyberpunk doesn’t do away with the economic struggles and “high-tech, low-life” mantra, instead it shifts the focus from the replayed characters and conflicts, showing us aspects of the world we have yet to explore.

Where 2021 was full of great sci fi short stories, “The Life Cycle of a Cyber-Bar” stands out as a cry for support, a new cyberpunk manifesto.

What do you think? Is cyberpunk bound for extinction, or are we witnessing the revival of the genre? Let us know in the comments below!

If you’re looking for more great sci fi short stories, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge Magazine, where we publish work from new and experienced authors alike, six times a year.

Classic Sci Fi Book Covers That Made The Genre

As someone who has a keen appreciation of old art, I find that many of today’s sci fi book covers lack a certain luster. In the course of forty or fifty years, we’ve moved away from book covers of full illustrations, painstakingly painted by hands by leading artists in the genre. Today, most sci fi book covers have an abstract quality that doesn’t say much about the book.

I know the adage, of course: “Don’t judge a book by its cover!” And yeah, for the most part that’s true. But as attention spans decrease and the flashy effects of TV and video games influence our tastes in science fiction art, book covers had to adapt to draw in new readers. Where there were once detailed oil paintings, there are now abstract, digital designs.

In this article, I want to showcase some of the classic sci fi book covers that helped defined the genre and influenced not just future art, but writing as well.

Darrell K. Sweet’s Red Planet by Robert A. Heinlein

Darrell K. Sweet is a big name when it comes to sci fi and fantasy illustration. He’s best known for his fantasy book covers for The Wheel of Time, The Lord of the Rings, and The Shannara Chronicles.

His grasp of fantasy concepts is really quite spectacular. As a kid, rummaging through library book sales and second-hand bookstore shelves, his art stuck out to me as an embodiment of the books themselves. His portrayals of Rand al’Thor, Gandalf, and the Eagles inspired me to not only read those books, but to explore his art as well.

Aside from fantasy masterpieces, Sweet was also known for his covers of Heinlein novels. While simple, the cover for the 1981 edition of Red Planet perfectly embodies the sci fi feel of Mars, while not being so weird it’s inaccessible.

The image of a massive Martian monster striding through a marsh of big frond leaves is serene, isn’t it?

Frank Frazetta’s The Moon Trilogy by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Frank Frazetta has a very specific style, and he’s gained renown for his work on Conan and Tarzan novels. He pits the classic, muscular heroes against hideous monsters with malicious eyes and sharp teeth.

He did a set of covers for Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Moon Trilogy, which was originally serialized in Argosy magazine from 1923 to 1925. Later, the series was reprinted in a few different editions, and Franzetta did the cover art for the 1978 reprint.

The art for The Moon Men, specifically, gives me a Hercules vibe, crossed with the scene from Star Wars where Luke is facing off against the Rankor. Frazetta does a great job of portraying conflict, and as I looked into more of his work, he has a keen sense of contrast. A lot of his paintings and classic sci fi book covers have a clear delineation from dark to light, making them super interesting.

Chris Foss’ Foundation Series by Isaac Asimov

The Foundation series is one of Asimov’s best works, and it was recently adapted for television. But, before it came to Apple TV, it had a lot of different imagery associated with it.

The series has been reprinted multiple times, but the edition that sticks out to me is the 1976 reprint with covers by Chris Foss.

Foss’ paintings usually focus on mechanical things, like spaceships, vehicles, or robots. He’s done designs from the Dune universe, as well as other military science fiction books.

Perhaps the most intriguing part about his illustrations for the 1976 Foundation books is the simplicity of them. The covers place an immense focus on the space ships, which perfectly reflect light and seem almost like a photograph. And the background is almost pure blue, presenting an interesting contrast between the hard light of the ships in the foreground.

Bruce Pennington’s Out of their Minds by Clifford D. Simak

Bruce Pennington is one of those sci fi illustrators that took their game to the next level. He’s worked on over 200 book covers for big-name writers, including Asimov, Heinlein, Aldiss, and Herbert.

However, the classic sci fi book cover that stuck out to me was for the 1973 edition of Clifford D. Simak’s Out of Their Minds.

Now, I’ve never read this book before, but I really want to. The cover Pennington did is fantastic. It’s weird, bright, and unforgettable. It features a huge tower/tree that resembles a brain, set against a barren landscape. It’s eerie. The truck is made of vertebra, and the rocks on the ground resemble molars.

I think this is a great example of how science fiction book covers can entice readers to pick up the book and give it a shot. All the other editions of Simak’s novel don’t stand out to me, but Pennington’s sparks a keen interest in what inspired the art.

At the end of the day, all I wanted to do with this article was talk about some vintage sci fi book covers that stand out more than some modern book covers ever could. I think the golden age of science fiction had a lot of problems – racism, sexism, imperialism, etc.—but it certainly had fantastic art.

What are some classic sci fi book covers that your really love? Let us know in the comments below!

Cowboy Bebop on Netflix is the Classic Anime Re-Imagined

Ever since the live action Cowboy Bebop on Netflix aired November 19th, 2021, the Internet has been alight with criticism. Wired wrote an article about how the show flops, and other popular news outlets claim the 46% Rotten Tomatoes score as an indicator of the show’s worth.

But, even though the new Cowboy Bebop show on Netflix might anger and frustrated hardcore fans of the classic 1998 anime of the same name, there’s a lot to love in this new show.

Some Background

The original Cowboy Bebop aired in 1998 as a singular season with 26 episodes. It quickly gained a cult following, and its jazz-fueled space noir style brought something new and fun to the cyberpunk genre.

In a world of 900-episode long anime series, Cowboy Bebop was blissfully short, but it packed far more of a punch than most of its counterparts. The anime won countless awards, including the 1st place at the 1999 Anime Grand Prix.

In 2017, there was talk of bringing the anime to life in a live-action series, and a year later, Netflix announced the show would come to their streaming platform. In 2021, we finally got to see years’ worth of work come to fruition, but fans were relatively unimpressed.

The live-action show hasn’t stayed entirely faithful to the source material, instead opting for a rendition instead of a truthful adaption.

And for many people, this ruffled feathers. Such an acclaimed and loved anime, seemingly defiled in another live-action remake.

However, there’s a lot to love about Cowboy Bebop on Netflix, and when we look at it as an alternative version of the anime instead of a poor adaption, it stands up on its own fairly well.

What’s to Love About Cowboy Bebop on Netflix?

As someone who watched the anime, the live action show took some getting used to. At first, I was a bit confused about the timeline and the story that the show was running with, but after a few episodes I was able to overlook the inconsistencies and view the show as a honoring of the source material.

The characters in the Netflix show are deep, motivated, and fun, more fun, I might say, then the original characters.

Faye Valentine, one of the female leads, has much more depth than in the anime. Her whole story revolves around not knowing her past, having been awoken from a cryogenic sleep with amnesia. Her motivations are realistic and her attitude mirrors the frustration she feels at living half a life.

In the anime, she’s very sexualized, which was a trope of anime of it’s time (frankly, it still is a trope), but the Netflix show re-imagines Faye as a badass bounty hunter with a me-against-the-world attitude.

And the banter that made me fall in love with the anime hits really hard in the Netflix show. I found myself laughing at the grumpy nature of Jet, Spike’s smart ass remarks, and Faye’s pithy one-liners.

For Spike, his transition to the big screen was the most intriguing. In the anime, there’s this duality about him. He’s funny and grim, full of heart and a scoundrel at the same time.

In the Netflix version, he oozes emotion, and is much less of an ass than in the anime. He builds relationships with Jet and Faye, and even though he keeps secrets, he’s much more loyal to his friends than in the anime. And this change made the Netflix show stand out.

They turned surly characters into deep, troubled heroes, but in a way that still follows the main themes of the source material.

What’s Stayed the Same?

One of the most endearing elements of the anime was the bounty-of-the-week style. Yes, there are plot-heavy episodes, but largely the story follows the Bebop’s crew as they hunt down wacky, villainous bounties.

And the Netflix show incorporates that while also running with a larger, underlying conflict.

We see those weird villains, like Mad Pierrot, and we see the more serious villains like Asimov and Vicious.

Vicious’ character in particular is deplorable. In the anime, he appears off and on as a returning antagonist, but in the Netflix show, he’s so full of emotion and violence, coming to life as more than a vague villain.

He has motivations and heartbreak, more than the anime allowed him to have. Despite being much more mad in the Netflix show, Vicious settles into his role of the big baddie very nicely.

Cowboy Bebop on Netflix is a Must-Watch

At the end of the day, if you are a big fan of the anime, watch Cowboy Bebop on Netflix as a loving rendition instead of an attempt to change the canon.

As a science fiction and fantasy enthusiast, it can suck to see a story you love adapted for screen. Take The Wheel of Time, for example. The first few episodes have changed a lot about the books, and while I’m irked by certain choices, I still enjoy seeing a series I love reach a wider audience.

Same goes with Cowboy Bebop. I guarantee that people who’ve never seen the anime will go back and watch it after binging the Netflix show, and will find something to love in both shows.

I hope we get to see more of Cowboy Bebop on Netflix. While the show hasn’t stayed true to its source material, it reinvents the anime, enriching the characters and making the cyberpunk noir setting really pop out.

Plus, I’m always down for some cowboy banter and Ein, the adorable Corgi sidekick.

5 Spooky Speculative Fiction Short Stories

We’re all familiar with speculative fiction short stories that instill a keen sense of dread in our hearts. When we think of classic horror stories, we might throw our minds to Frankenstein, Dracula, or other Gothic terrors.

But there are many more stories out there that leave readers huddled under their covers, sleeping with the lights on.

As far as spooky speculative fiction short stories go, you might be familiar with the big ones. Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”, Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”, and Poe’s “The Tell Tale Heart” all ring a bell.

But from deep in the annals of long-gone spec fic magazines, there come new contenders for the throne of horror.

Keep reading, if you dare…

Mop-Head by Leah Bodine Drake

“Mop-Head” was first published in the January 1954 issue of Weird Tales. It was later included in various anthologies, the most recent being the Weird Tales Super Pack #1, released in 2018.

This horror short story is set in the open fields of Kentucky, where the Loveless children Dorothy and Harry Todd mourn the loss of their mother, Reba.

But alas! All is not lost; they have a friend in Mop-Head. He’s their confidante and saving grace, their only hope of seeing their real mother again.

Things get creepy as the mysterious amalgamated Mop-Head climbs from his old well, his sole purpose to fulfill his promise to the young Loveless children.

Drake’s style dribbles unsettling imagery throughout the whole story. Take, for example, the line: “From darkness and silence and damp, out of earth-mold and wet leaves and blown dandelions, of scum and spiders’ legs and ants’ mandibles and the brittle bones of moles, it formed a shape and a sentience.”

The slow buildup of horrifying imagery is what makes this story interesting, and the quick resolution in the end reassures us that everything will be alright.

Do take this story with a grain of salt. Written nearly 70 years ago, the dialect of the African American characters reads like Mark Twain, and was a bit off-putting.

Here’s a reading of “Mop-Head” by my friend Douglas Gwilym.

“Miriam” by Truman Capote

“Miriam” first appeared in the June 1945 issue of Mademoiselle magazine, and was one of Truman Capote’s very first short stories.

Unlike “Mop-Head”, there are no abysmal horrors to be found here. Instead, a mysterious little girl, Miriam, seemingly haunts an old woman named Mrs. Miller.

Capote’s sense for setting is unmatched, and he instills a cold, creepy tone into a once harmless story with this line: “Within the last hour the weather had turned cold again; like blurred lenses, winter clouds cast a shade over the sun, and the skeleton of an early dusk colored the sky.”

“Miriam” reminds me of “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but with far less of a clear answer as to what’s happening. There are many interpretations of “Miriam” and all of them are equally as creepy. This story definitely fits the bill as a spooky speculative fiction short story.

“Spider Mansion” by Fritz Leiber

“Spider Mansion” was originally published in the September 1942 issue of Weird Tales. It comes from one of the founding fathers of sword and sorcery, Fritz Leiber.

The story starts of like all classic horror stories do, at an ancient mansion in the midst of a thunderstorm. Tom and Helen Egan call upon their old friend Malcolm Orne. They are much surprised when they’re greeted by a seven-foot giant instead of the three-foot tall Malcolm they used to know.

“Spider Mansion” operates on the fringes of science fiction, but right in the middle of horror. As the name suggest, there’s no lack of creepy crawlies in this speculative fiction short story.

And like “Mop-Head”, it should be read with a grain of salt. The slight racism of Malcolm’s character makes him that much more deplorable.

“The Portrait” by Nikolai Gogol

This is by far the oldest speculative fiction story on this list, and it falls in line with more Gothic, classic literature.

“The Portrait” by the Ukrainian author Nikolai Gogol was first seen in Arabesques, a short story collection published in 1835.

The story follows the rise and fall of a young artist, Andrey Petrovich Chartkov, known in the story as Tchartkoff. He purchases an eerie painting of an old man with his last few coins, but is pleasantly surprised when the portrait produces a vast sum of money, seemingly from thin air.

This story is a real slow-burner, and a bit long-winded at times, but the imagery, especially in the first few scenes, is incredibly profound.

Even in 1835, people where frightened of moving eyeballs in portraits!

You can read the full story here.

A Microfiction: “Active Imagination” by Michelle Wilson

While doing some casual reading on the web, I came across this microfiction piece by Michelle Wilson, published on 50-Word Stories.

It’s weird, and takes a turn at the end I never expected. But I like it, and maybe you will too.

Hopefully these spooky stories send a shiver down your spine, I know they certainly did for me. May you all have a hauntingly swell Halloween!

Understanding Sci Fi Subgenres: Gothic Science Fiction

Aaaand we’re back to break down more sci fi subgenres, this time we’re delving into the creepy, weird world of gothic science fiction!

For many people, hearing the words ‘gothic science fiction’ brings back memories of high school English class and Mary Shelley’s magnum opus, Frankenstein.

And certainly, Frankenstein is one of the pinnacle works in this sci fi subgenre, but it also largely inspired the genre as we know it today.

What is Gothic Science Fiction?

Gothic science fiction sits in that liminal space between two genres. On one hand, it takes a lot of aesthetics and themes from traditional gothic fiction, and on the other hand, it incorporates controversial or untested sciences to push the boundaries of creepy.

Gothic fiction dates back to the late 1700s and early 1800s, but has remained a steadfast genre to modern day. Where Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley, Eleanor Sleath, and Samuel T. Coleridge put the arcane into writing by candlelight, authors like Toni Morrison, Steven King, and Joyce Carol Oates brought the supernatural into the electric-light of modernity.

One of the staples of Gothic fiction has always been a fascination with the mysterious and the unexplainable. In Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), a massive helmet falls from the sky to kill one of the characters, and skeletal apparitions walk the castle halls at night. In many ways, the supernatural in Gothic fiction motivates characters to say and do things they might not normally do. Pure fear and confusion drive them to the ends of their wits, and this terror of human uncertainty is what makes Gothic fiction unique.

In modern horror, yes, motivations are driven by fear, but ultimately the unexplainable and the mysterious are more than just a catalyst. They’re a key component in the reaction of the reader or viewer.

Think of it like the difference between a jump scare and a lingering fear. When a demon or a ghoul lurches abruptly onto the screen, the audience lets loose a scream of horror. But when the fear builds up across the whole book or novel, it leaves the audience unable to sleep at night, unsettled even in the security of their own home.

The 2017 IT movie makes use of the jump scare, whereas something like The Telltale Heart employs an exponentially-growing fear that lingers even after the last page.

Other conventions of Gothic fiction include:

- Medieval or ancient settings (castles, old churches, ancient barrows, etc.)

- An emotional response (the lingering fear brought on by what Edmund Burke describes as the Sublime)

- Political or sociopolitical undertones (The Mask of Anarchy by Percy Shelley pairs Gothic themes with a plea for nonviolent resistance)

Putting the Science in Goth Science Fiction

While the occult and the supernatural play a large part in defining traditional Gothic fiction, the addition of science takes the genre to new heights.

Take Frankenstein, for example. Most of what makes the story compelling is the deep moral quandary and tragedy of Victor Frankenstein, brought on by his dabbling in arcane sciences, namely the reanimation of dead tissue. Shelley’s use of science in Frankenstein is a vehicle for plot progression, and largely a catalyst for her character’s ongoing psychosis.

Vampirism is another good example. There are two sides to the same coin.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, brought vampires into the limelight. In a traditional Gothic sense, vampires are creatures of folklore, hearkening back to medieval eras. The story of the 2014 film Dracula Untold follows in Stoker’s footsteps, with the source of horror coming from an ancient creature, presumably Nosferatu. Science has no part in the film.

But, in a Gothic science fiction sense, vampirism might be defined as a genetic or blood disease rather than a result of the supernatural. Renfield Syndrome is the clinical definition we use today to describe an all-encompassing obsession with blood. The condition was named after a character in Stoker’s book.

Using science as an explanation for the occult might seem like a visible deconstruction of the Gothic genre, but in many ways it elevates the elements of horror.

Today, reading Dracula or Frankenstein by itself with no adjacent literature to define them, they seem a bit less scary than they probably were a hundred years ago. They are rooted in a fear of the unexplainable, and use that fear as a vehicle for plot.

This is because modern science and all of its tools are able to help explain some of the phenomena found in traditional Gothic novels (aside from, perhaps, helmets falling from the sky).

The unexplainable is no longer so foreign anymore, is it? Vampirism isn’t the result of an arcane horror, but rather a disease we can define in clear terms. Apparitions can be explained as unique phenomena based on environment, atmospheric conditions, etc. etc.

Taking this Scully-ish approach breaks down the key mechanism of Gothic fiction which is the fear of the unknown. So how do we keep a genre alive when its kingpin tactic has been jeopardized?

What Makes Gothic Science Fiction?

You might be thinking, ‘Gothic fiction still stands today because people are still scared of the unknown’ and you’d be right. As viewers, we can appreciate the Gothic genre for what it is, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t creeped out by The Castle of Otranto or “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

What I’m proposing is that Gothic science fiction is the evolution of Gothic fiction, that this sci fi subgenre is an adaptation of traditional themes meant to appeal to a modern audience.

As a modern reader, the difference between the 1897 Dracula and the 1954 I Am Legend is that Matheson incorporates the idea of the occult—vampirism—and skews it in a science fiction way. In 2021, where electric light and technology reach even to the deepest corners of our lives, a vampiric pandemic inspires more fear than whatever arcane horror might be lurking in ruined castles.

The potential for a widespread blood-sucking, zombifying disease seems a lot more plausible than stuff of folklore because it preys on our fear of the scientific unknown. By that I mean that for those of us that lack the scientific literacy to explain a vampiric disease, it serves the same purpose as any other mysterious Gothic fears we don’t understand.

The core tenant of Gothic fiction is the unexplainable, but our definition of the unexplainable has changed from 200-hundred years ago. And that’s where science comes into play, because the vast majority of us can’t explain how vampiric diseases, the fabric of reality, or extraterrestrial phenomena work. For the viewer, the new unexplainable is on the fringes of science.

In Conclusion

I guess something that occurred to me while writing this is that Gothic science fiction doesn’t seem to have a linear timeline. There isn’t a “this was the first book ever written and here’s the most recent”. It’s a theme that can be transposed on many works, even if they were written a hundred years apart.

At the end of the day, what Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde started, modern science fiction authors modify to keep up with the pace of technological and scientific advancement.

Everyday the bounds of the unknown get pushed farther back, and the Sublime morphs to account for the forward march of science.

As one of the prominent sci fi subgenres, Gothic science fiction continues the tradition of putting into words what we think about at the darkest hour of night.