Young readers are starting to consume sci fi literature with voracious speeds, but for those just getting into the genre, where do you start?

Everyone raves about Divergent, Hunger Games, and Shadow and Bone, but what other science fiction books for teens are out there?

Here’s a selection of the best sci fi books for young adults, old and new alike.

Have Space Suit – Will Travel by Robert Heinlein

Length: 258 pages

ISBN: 9780345324412

Published In: 1958

Heinlein enthralls readers with the tale of Kip Russell and his dream of traveling to the moon. Russell gets up to all kinds of shenanigans, but it all starts when he participates in an advertising jingle-writing contest in order to win a fully-paid ticket to the moon. Instead, he wins a used spacesuit, which he fixes and names Oscar.

To help pay for college, Kip considers selling the suit but decides to go out with it for one last walk, and suddenly he starts receiving signals from an 11-year-old girl called Peewee and an alien friend called Mother Thing.

Moments later, a spaceship lands almost on top of him, and it is his alien friends, but the three of them are quickly kidnapped by the alien Wormface. The story follows their escape and adventures in space.

The Giver by Lois Lowry

Length: 240 pages

ISBN: 9780544336261

Published In: 1993

The Giver is one of those books that people either love or they hate. Some middle/high schools make this book required reading, which might be why it’s loathed by so many. But, it’s a classic in the YA sci fi genre, and a large influence to more recent dystopian sci fi.

The Giver tells the story of 12-year-old Jonas, living in a small community where everyone gets a life-assigned role.

When the day to receive his life assignment comes, Jonas gets an unusual and high-status role called the Receiver. This role requires certain training from the present Receiver of town, which costs him his relationship with his friends and family and a lifetime of abnormal missions and events.

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle

Length: 416

ISBN: 9781250056948

Published: 1962

Another sci-fi classic, Wrinkle follows 13-year-old Meg Murry, the child genius brother Charles Wallace, and Calvin O’Keefe traveling through the universe to find Meg’s father disappeared while studying and working on the scientific phenomenon called the “Tesseract”.

A Wrinkle in Time was recently adapted into a film starring Reese Witherspoon, Chris Pine, Mindy Kaling, and Oprah Winfrey.

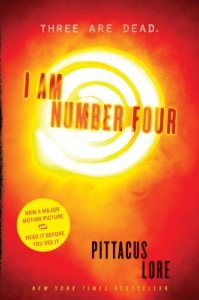

I Am Number Four by Pittacus Lore

Length:440

ISBN: 9780061969577

Published In: 2010

I Am Number Four is the first book in a seven book series, and it follows the lives of multiple refugee aliens on Earth.

John Smith, who is the titular number Four, is thrust into a galactic battle to avenge his home planet, Lorien, and to protect Earth from the Mogadorians. But, the high school kid can’t do it by himself, so he enlists the help of his fellow students and his few remaining alien compatriots.

If you are looking to start on a saga, maybe you just found it!

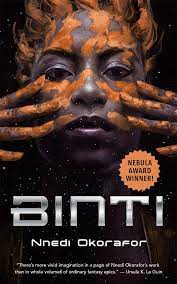

Binti by Nnedi Okorafor

Length: 96 pages

ISBN: 9780756416935

Published In: 2015

Binti has won multiple awards, and is revered as one of the staples of modern Afrofuturism.

The main character, Binti, is the first of the Himba people to attend Oomza University, a high-status learning institution in the galaxy. But to attend, Binti must abdicate her place with her family to travel the galaxy with strangers who don’t respect her customs and beliefs.

Binti, and it’s subsequent novels, are an in-depth coming of age tale, perfect for anyone just entering middle or high school.

Rabbit & Robot by Andrew Smith

Length: 448

ISBN: 9781405293983

Published In: 2018

This book offers even more space-traveling fun! The main character, Cager Messer, who is transported to the Tennessee, his father’s lunar-cruise ship orbiting the moon, next to his friends Billy and Rowan.

While Earth destroys itself by going through several simultaneous wars, the robots onboard the cruise start becoming more and more insane and cannibalistic, making the boys wonder if they will be stranded alone in space for the rest of their lives.

This Mortal Coil by Emily Suvada

Length: 464

ISBN: 9781481496346

Published In: 2017

Truly a book for our times, This Mortal Coil tells the story of Catarina, a girl trying to decrypt the clues for a vaccine against a devastating virus developed by her dad, the world’s most renowned geneticist.

This dystopian thriller is one of the best science fiction books for teens because it directly relates to the dangers of the world we’re all living in right now.

Illuminae by Amie Kaufman and Jay Kristoff

Length: 608

ISBN: 9780553499117

Published In: 2015

Teen romance gets sticky when the end of the world is near! Kady’s planet gets invaded by enemies during a war between two rival megacorporations, and both Kady and Ezra are forced to evacuate together.

While new threats come to the surface, Kady realizes that the only one able to help her is her ex-boyfriend, who she swore never to speak to again.

A sci-fi novel with a touch of teen drama? Sign me up. Plus, there’s plenty to soak in, with a whopping 600 pages!

Did you enjoy our selection of the best science fiction books for teens? Let us know in the comments if you have read any of them or which you’ll be reading next!

And if you want some more great science fiction stories, interviews, and book recommendations, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge Magazine.