Qntm (pronounced “quantum”) is a software developer and a writer known for pushing the limits through his mind-bending stories that incorporate science, horror, science fiction, and alternatives to the reality we live in as humans on Earth. We sat down to chat with qntm about his most recent publication.

Continue reading “INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR QNTM ON HIS LATEST BOOK”Category: Writing

Interview with Author Mica Scotti Kole

An award-winning author, and a regular to the pages of Galaxy’s Edge Magazine, writer and editor Mica Scotti Kole gave us the chance to peal back the pages and get a glimpse inside the life of a dreamer, artist, and someone who has followed her dreams straight into a reality …

Continue reading “Interview with Author Mica Scotti Kole”Rick Riordan Presents Widens The Scope Of MG Mythology

Back in the mid-2000s, I was a big fan of Rick Riordan’s Percy Jackson and the Olympians series, like most middle-schoolers were.

I had always been interested in mythology, but a lot of the books I was reading weren’t gauged toward a young audience. Riordan’s famous series gave traditional Greek myths a fun twist, and I naturally gobbled up everything he wrote for many years.

By about high school, I had kind of fallen out with Riordan’s work. His Percy Jackson series had been replaced by its Roman counterpart, which I just didn’t find as interesting. His Egyptian mythology series, The Kane Chronicles, was one of the last things I read of his work, and I appreciated it, but wasn’t as impressed as I might have been if I were a few years younger.

As I started to read more about mythology on my own, I started to realize that in some ways, Riordan was starting to tread into dangerous territory. Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Norse mythologies are all pretty mainstream at this point, with ideas or deities appearing in film and novels, everything from American Gods to Marvel and DC comics.

But at one point, I remember thinking, “Riordan’s exhausted most of his avenues at this point, he’ll have to start diving into other cultural heritages for inspiration.” And that troubled me a bit, simply because Riordan is a middle-aged white dude, how will he tackle African mythology? Japanese, Korean, Chinese mythology? Really, any mythos outside of the classic four he’d already written about.

That’s when I learned about Rick Riordan Presents, his publishing imprint through Disney-Hyperion, so to speak.

What Is Rick Riordan Presents?

On their website, Riordan states that the Rick Riordan Presents imprint is meant to “help other writers get a wider audience. I also want to help kids have a wider variety of great books to choose from, especially those that deal with world mythology, and for all kinds of young readers to see themselves reflected in the books that they read.”

In this light, it’s important to note that the Rick Riordan Presents books aren’t a part of the Percy Jackson universe, but are instead independent books that Riordan only helped to edit and publish.

The whole point of the imprint is to bring more voices into the middle-grade mythology scene, and I certainly think that Riordan and his team have succeeded in that goal.

Breaking Out Of The Mold

Anyone who has read science fiction and fantasy for any amount of time knows that there’s an incredible amount content out there that’s inspired by mythology, even if only in passing.

Paranormal investigation series written by people like Seanan McGuire or Jim Butcher riff off certain myths and legends, while other stories, recreate classical story structure down to a tee.

After talking with PJ Manney about the New Mythos and how we need to change the way we tell stories, I realized that a lot mythology-inspired fiction draws on the big four (Greek, Roman, Egyptian, and Norse). And those stories reflect a mindset that’s already been repeated throughout mainstream media and storytelling practices for hundreds of years.

Greek plays, Roman epics, Norse origin stories—they all work under the shadow of outdated story structures that are clearly linked to the power and politics of the times.

So naturally, there needs to be a revolution, so to speak, where our classical mythologies get sent to the bench for a while and new stories take to the field.

And that’s where Rick Riordan Presents starts to do its work.

Books from Rick Riordan Presents

As it stands, the Rick Riordan Presents imprint has brought many mythologies to middle school libraries outside of the big four. Here’s a list of some of the books the imprint has published, or plans to publish.

The Pandava Quintet – a five book series by Roshani Chokshi. The series kicks off with Aru Shah and the End of Time, and focuses heavily on Hindu mythology.

The Storm Runner Series – this trilogy was written by J. C. Cervantes and brings Aztec and Mayan mythology to the board. A follow-up series, Shadow Bruja, dives into a character from the first trilogy in the same realm of mythology.

The Thousand Worlds Series – So far, there are two books in this series written by Yoon Ha Lee. Where other books in the imprint are grounded on our Earth, Thousand Worlds takes us into space and explores Korean mythology. The first two books are Dragon Pearl and Tiger Honor, with a potential third book in the works.

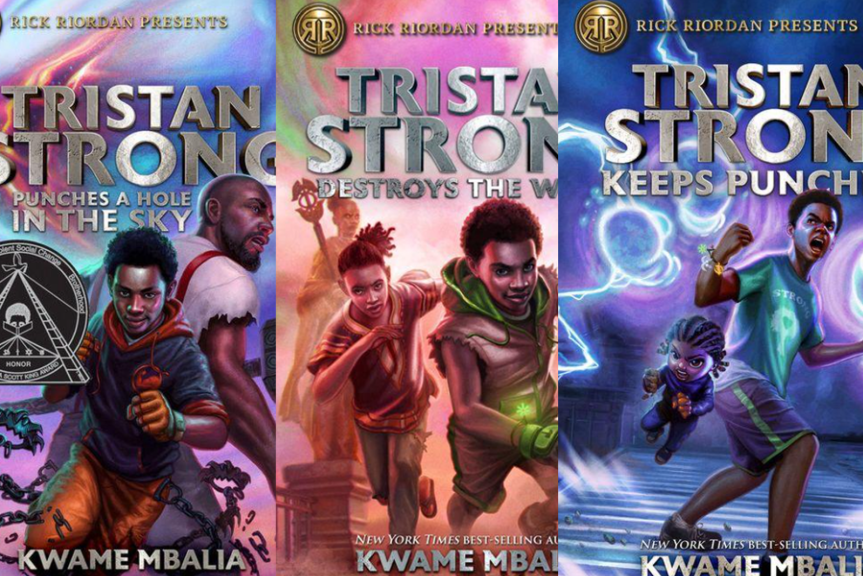

The Tristan Strong Series – this trilogy was written by Kwame Mbalia and explores African-American and West African mythology. The first book, Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky, tackles dealing with grief, while the other books dive more into cultural heritage. There is a graphic novel adaption in the works, too.

Sal & Gabi – This series was written by Carlos Hernandez and dives into Cuban mythology. This sci-fi/fantasy crossover series has two books, Sal and Gabi Break the Universe and Sal and Gabi Fix the Universe.

The Paola Santiago Series– This trilogy was written by Tehlor Kay Mejia and takes a new approach to middle-grade mythology, with a supernatural focus on Hispanic myths and legends. The first book, Paola Santiago and River of Tears was rated as one of Amazon’s Best Books in 2020.

The Gifted Clans – Graci Kim’s Korean-mythos series started off with The Last Fallen Star and has two more books slated for release.

In addition to the series, Rick Riordan Presents has also published two standalone novels, by Rebecca Roanhorse and Sarwat Chadda. Plus, The Cursed Carnival was an anthology edited by Riordan that featured short stories set in the universes of each series.

Upcoming projects feature authors like Daniel José Older, Tracey Baptiste, Stacey Lee, and Roseanne A. Brown.

Conclusion

While this blog post might have rambled on for a bit, I just want to say that I’m glad Rick Riordan put his focus onto bringing more diverse voices into the middle-grade mythology scene. His books are great, but they’re written from a certain point of view that’s been redone multiple times across the board.

Giving all of these authors a cohesive platform to work with is a great opportunity to teach kids about different cultural heritages and turn them onto exploring the legends and beliefs of cultures they might not have been able to explore otherwise.

I wish that these books—or books like these—had been around when I was reading Percy Jackson. Perhaps my sense of storytelling and mythology might be a lot stronger had they been.

Breaking Up The Story: What is Serialized Fiction?

In many ways, the Internet completely changed how we look at fiction. What was once a very tangible thing—think magazines, books, newspapers, etc.—has become somewhat immaterial. You can’t hold a magazine issue digitally; you’re holding your phone or tablet, and it’s just not the same.

If you didn’t have a subscription to your favorite science fiction magazines back then, you could head to the library, borrow a friend’s or check out the corner store.

Now, it seems that physical magazine subscriptions are few and far between. Why pay for a tangible thing when you can save money by reading the stuff online for a fraction of the cost, sometimes for free?

That paradigm shift comes with its own quirks. If you happen to forget to bookmark a short story you read in some magazine, it might be completely lost to you if you end up forgetting author, title, and place of publication.

If you had the magazine on your shelf, all you had to do was flick through until you found it. Now you have to scroll through the archives, opening a thousand tabs to find the story. Or worse, attempt to prod the collective mind on Reddit or Twitter.

However, one of the interesting things about the relationship between the Internet and fiction is serialized fiction, which is a format that predates the Internet, but has gotten so much more traction because of it.

What is Serialized Fiction?

Serial fiction, or serialized fiction, is when a longer work is broken up into smaller installments that are released on a set schedule. Think TV episodes, but for fiction.

Where do serials appear? They can pop up in monthly, bi-monthly, weekly, or daily publications, like magazines or newspapers. Not only is serialized fiction a great way for authors to keep interest in their work going for a long time, it’s also used as a tool to sell more magazines or newspapers. If people get invested in the serial, they’re going to have to keep buying to read!

Serialized fiction is by no means a new concept. It’s been around for hundreds of years, and picked up popularity when the printing press made reading material more readily available for people outside of the aristocracy.

Charles Dickens had Great Expectations serialized in 1860, and Arthur Conan Doyle wrote many of the Sherlock Holmes stories to appear sequentially in various magazines.

Fast forward a hundred years, radio and television drastically changed the world of serialized fiction, bringing a more lifelike element to it. Even comic books work on the same principle as early serialized specials.

But what about today? And what about SFF publications? Where do they stand?

Serialized Fiction in 2022

The Internet has made writing fiction like Charles Dickens did nearly impossible. Sometimes, scenes in Dickens’ novels stretch for pages at a time, barely broken by dialogue or action of any kind. Unless you’re hyper-focused on the text, it’s difficult to read it without drifting off into daydreams or switching to a more engaging activity.

And we have the Internet and social media to blame for a lot of that. Recent studies have shown that the human attention span is about 8 seconds, which is why so many videos on Instagram and TikTok are limited to under 60 seconds. Anything longer, people just won’t watch it.

Even the way we have to format writing has changed. Gone are the long paragraphs, which were replaced with white space every two or three sentences.

So, it was only natural that serialized fiction would make an appearance in the new digital world. The bite-sized installments are easy to handle, and fit into even the busiest schedules.

Ways to Read (and Listen)

Now, more than ever, serialized science fiction and fantasy works are on the rise. Serial Box, which has since become Realm, features episodic fiction from authors like Max Gladston, K. Arsenault Rivera, E.C. Meyers, Yoon Ha Lee, Mary Robinette Kowal, and so many more.

Realm offers readers multiple installments of the same story in podcast format. Generally, each episode is about an hour and a half long, which makes it easy to find a stopping point.

However, the contrast between the 8 second attention span and the 1.5 hr episode length is pretty distinct.

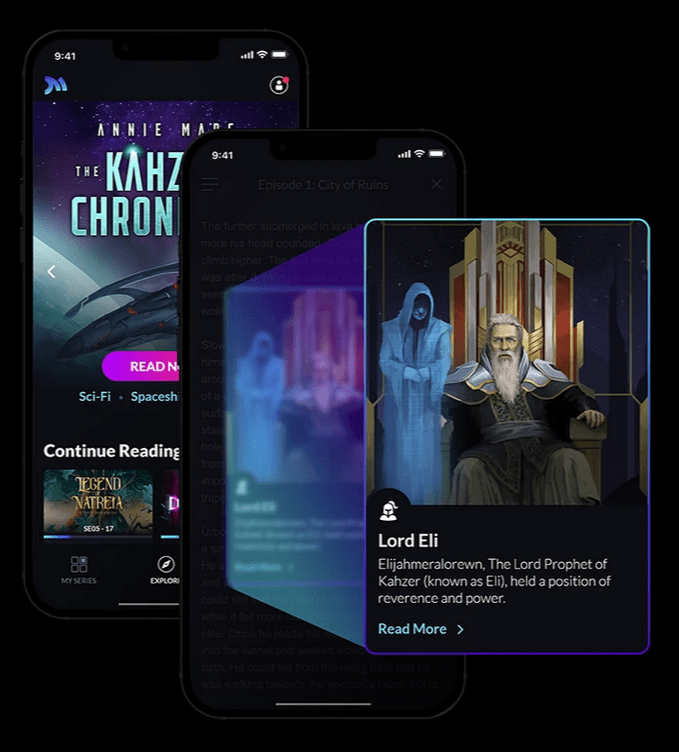

Other serialized fiction platforms, like Mythrill Fiction, break stories down into much more manageable chunks.

On their app, Mythrill has a handful of different stories, ranging in themes from pirates and sea monsters to cyberpunk cities.

Each story is broken up into 20 episodes, with each episode taking about 5 minutes to read.

But, the really interesting thing about Mythrill is their lore cards. These story add-ons help readers quickly get a grasp of the characters and the world, and each come with an illustration.

There are also many serialized fiction podcasts out there, similar to Realm, that have continuous stories that are released in episode installments. Check out our article on SFF podcasts to learn more.

Conclusion

Why do I think serialized fiction is the way we’re going to be reading and listening to SFF in the future? It’s tailored to the current human experience. It might sound dumb, but having fiction that fits into your lifestyle—almost like how Duolingo makes language-learning manageable—is the key to garnering a following.

Don’t get me wrong, I love big books. The Stormlight Archive, Dandelion Dynasty, The Wheel of Time, etc., but more and more I find myself daunted by the sheer size of them.

Who knows, I might be wrong, but now, I see serialized fiction becoming much more popular in the coming years simply because it formats its content in ways we’re accustomed to consuming Internet media.

What are your thoughts? Let us know in the comments below.

Nebula Award 2021 Nominations

It’s that time of year again! SFWA just announced all the nominations for the Nebula Award 2021.

All finalists had their science fiction, horror, or fantasy work published in 2021, and the winners for each category will be announced on Saturday, May 21, 2022 during a virtual ceremony. Eligible SFWA members will be able to start voting on March 14th, 2022.

We are super excited to share that Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s story, “O2 Arena”, that was published in Galaxy’s Edge issue 53 last year is a finalist for the Nebula Award for Novelette!

If you would like to read his novelette, you can do so here.

We also provided links to read all of the work that has been published online. Without further ado, here are all the Nebula Award Finalists for 2021:

Best Novel

- The Unbroken, C.L. Clark (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- A Master of Djinn, P. Djèlí Clark (Tordotcom; Orbit UK)

- Machinehood, S.B. Divya (Saga)

- A Desolation Called Peace, Arkady Martine (Tor; Tor UK)

- Plague Birds, Jason Sanford (Apex)

Best Novella

- A Psalm for the Wild-Built, Becky Chambers (Tordotcom)

- Fireheart Tiger, Aliette de Bodard (Tordotcom)

- And What Can We Offer You Tonight, Premee Mohamed (Neon Hemlock)

- Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters, Aimee Ogden (Tordotcom)

- Flowers for the Sea, Zin E. Rocklyn (Tordotcom)

- The Necessity of Stars, E. Catherine Tobler (Neon Hemlock)

- “The Giants of the Violet Sea“, Eugenia Triantafyllou (Uncanny 9–10/21)

Best Novelette

- “O2 Arena“, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (Galaxy’s Edge 11/21)

- “Just Enough Rain“, PH Lee (Giganotosaurus 5/21)

- “(emet)“, Lauren Ring (F&SF 7–8/21)

- “That Story Isn’t the Story“, John Wiswell (Uncanny 11–12/21)

- “Colors of the Immortal Palette“, Caroline M. Yoachim (Uncanny 3–4/21)

Best Short Story

- “Mr. Death“, Alix E. Harrow (Apex 2/21)

- “Proof by Induction“, José Pablo Iriarte (Uncanny 5–6/21)

- “Let All the Children Boogie“, Sam J. Miller (Tor.com 1/6/21)

- “Laughter Among the Trees“, Suzan Palumbo (The Dark 2/21)

- “Where Oaken Hearts Do Gather“, Sarah Pinsker (Uncanny 3–4/21)

- “For Lack of a Bed“, John Wiswell (Diabolical Plots 4/21)

Andre Norton Nebula Award for Middle Grade & Young Adult Fiction

- Victories Greater Than Death, Charlie Jane Anders (Tor Teen; Titan)

- Thornwood, Leah Cypess (Delacorte)

- Redemptor, Jordan Ifueko (Amulet; Hot Key)

- A Snake Falls to Earth, Darcie Little Badger (Levine Querido)

- Root Magic, Eden Royce (Walden Pond)

- Iron Widow, Xiran Jay Zhao (Penguin Teen; Rock the Boat)

Ray Bradbury Nebula Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation

- Encanto, Charise Castro Smith, Jared Bush, Byron Howard, Jason Hand, Nancy Kruse, Lin-Manuel Miranda (Walt Disney Animation Studios, Walt Disney Pictures)

- The Green Knight, David Lowery (Sailor Bear, BRON Studios, A24)

- Loki: Season 1, Bisha K. Ali, Elissa Karasik, Eric Martin, Michael Waldron, Tom Kauffman, Jess Dweck (Marvel Studios)

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, Dave Callaham, Destin Daniel Cretton, Andrew Lanham (Walt Disney Pictures, Marvel Studios)

- Space Sweepers, Jo Sung-hee 조성희 (Bidangil Pictures)

- WandaVision: Season 1, Peter Cameron, Mackenzie Dohr, Laura Donney, Bobak Esfarjani, Megan McDonnell, Jac Schaeffer, Cameron Squires, Gretchen Enders, Chuck Hayward (Marvel Studios)

- What We Do in the Shadows: Season 3, Jake Bender, Zach Dunn, Shana Gohd, Sam Johnson, Chris Marcil, William Meny, Sarah Naftalis, Stefani Robinson, Marika Sawyer, Paul Simms, Lauren Wells (FX Productions, Two Canoes Pictures, 343 Incorporated, FX Network)

Nebula Award for Game Writing

- Coyote & Crow, Connor Alexander, William McKay, Weyodi Oldbear, Derek Pounds, Nico Albert, Riana Elliott, Diogo Nogueira, William Thompson (Coyote & Crow, LLC.)

- Gramma’s Hand, Balogun Ojetade (Balogun Ojetade, Roaring Lion Productions)

- Thirsty Sword Lesbians, April Kit Walsh, Whitney Delagio, Dominique Dickey, Jonaya Kemper, Alexis Sara, Rae Nedjadi (Evil Hat Games)

- Wanderhome, Jay Dragon (Possum Creek Games)

- Wildermyth, Nate Austin, Anne Austin (Worldwalker Games, LLC, Whisper Games)

Congratulations to all of the finalists! 2021 was truly a great year for science fiction, fantasy, and horror. We’re looking forward to seeing the results in May!

If you read “O2 Arena” by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and you want to read more from Galaxy’s Edge, consider becoming a subscriber:

Science Fiction Anthologies To Watch For in 2022

With the new year fast approaching, there’s a whole new lineup of science fiction anthologies to get excited about.

Personally, I find that science fiction anthologies are the best of both the novel and short story worlds. You get the thick book like a novel, but you get dozens of individual stories, some connected by theme or place and time.

In this blog, we’ll run down some of the newest science fiction anthologies coming our way in 2022.

The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories

This anthology is a collection of translated short stories from Chinese SFF writers. They focus heavily on fiction from female and nonbinary writers, and the team behind the anthology has a long history in the genre.

Regina Kanyu Wang, one of the editors, has frequently appeared in Clarkesworld Magazine, was featured in Ken Liu’s Broken Stars anthology, and had a story published in the March 2018 issue of Galaxy’s Edge Magazine.

Yu Chen, the other editor of this science fiction anthology, has also been involved in the SFF community for a long time. She’s presented at workshops, conventions, and published multiple books from Asian sci-fi writers like Han Song and Song Mingwei.

I’m looking forward to this anthology, and will definitely grab it on release day, March 8th, 2022.

The Best Science Fiction of the Year

I always look forward to Neil Clarke’s anthologies. His collection of the best science fiction short stories always boasts some of the year’s most intriguing, thoughtful pieces from new and established writers alike.

This will be the sixth anthology in the best of the year series, featuring stories from Yoon Ha Lee, Annalee Newitz, Rich Larson, and Ann Leckie, to name a few.

This science fiction anthology will hit shelves on January 25th, 2020.

Triangulation: Energy

Triangulation is one of the oldest science fiction anthologies that I know of. They started publishing spec fic short stories in the early 2000s, and have kept up the yearly tradition ever since. Each issue has a specific theme, and for the past few years they’ve covered sustainability topics like light pollution, eco-friendly housing, and biodiversity.

This year’s anthology will feature stories about sustainable energy, and all that that encompasses.

While there isn’t an exact date for the anthology yet, they are usually released at the end of the summer.

Check out the interview we did with Diane Turnshek and John Thompson, the editors of the 2021 anthology, Triangulation: Habitats.

The Reinvented Heart

This anthology is edited by Cat Rambo and Jennifer Brozek, and seeks to explore emotional relationships in science fiction.

So much of sci fi is caught up in the physical tech, and often overlooks emotional responses to those same technologies. This science fiction anthology is filled with stories and poems about “how shifting technology may affect social attitudes and practices.”

The anthology features work from Jane Yolen, Seanan McGuire, Ana Maria Curtis, Aimee Ogden and more!

Watch out for this anthology on March 10th, 2022.

Orpheus + Eurydice Unbound

This speculative fiction anthology is expected to release in the summer of 2022 from Air and Nothingness Press.

The anthology will feature stories that re-imagine the Orpheus and Eurydice story from Greek mythology. The book will consist of four sections, with stories that fit each step of the mythological tale, including The Wedding, The Snake, The Quest, and The Look Back.

The theme seems to be fairly narrow, but I have confidence that it will be an exception anthology. Air and Nothingness Press has a reputation for putting out great books, and this one should be no different.

Professor Feif’s Compleat Pocket Guide to Xenobiology for the Galactic Traveler on the Move

This one seems super fun! Dedicated to all flora and fauna of the alien worlds, as far flung as they may be, this anthology is bound to be filled with interesting stories of carnivorous plants, oozing goop, and other weird things.

This science fiction anthology from Jay Henge Publishing has yet to get a solid release date, but I assume it will appear sometime in 2022. Jay Henge has published numerous science fiction anthologies, including Sunshine Superhighway, Sensory Perceptions, and The Chorochronos Archives.

What sci fi anthologies are you excited for? Let us know in the comments below!

And if you’re looking for a New Year’s gift, nothing is better than a subscription to Galaxy’s Edge!

Keep Driving: The Importance of Sci Fi Cars

In 2012, George F. Will wrote an opinion piece for The Washington Post about the American dream and the automobile.

While his pithy piece hits on many points, his primary thesis is that cars have a way of identifying a person, as well as establishing a ‘self-image’. He cites Paul Ingrassia’s book, Engines of Change: A History of the American Dream in Fifteen Cars, which speaks at length about establishing identity through vehicular choice.

It’s certainly an interesting theory. You see a person driving a Prius and you already have this notion of who they are in your head. They’re conscious of their impact on the environment, they value efficiency over style, they’re probably a Democrat, etc. etc.

But the theory works both ways. We can assume things about people based on their choice of car, but we as individuals can also craft our identity through our cars.

For example, my first vehicle was a 2001 Mazda B4000, a small pick-up truck. I was in college, I need a way to move my stuff, and I liked the rugged look of an older truck.

But now, I drive a 2005 Subaru Outback. I still appreciate rugged, older vehicles, but I’ve replaced aesthetic with efficiency.

What I’m getting at here is that we begin to craft stories around our vehicles and identify ourselves through our relationship with vehicles.

The same goes for sci fi cars in movies, TV shows, comic books, novels, etc. Writers often use vehicles as a way to express something about a character, and they often gain a life of their own.

Writing Character With Sci Fi Cars

One of the primary examples I want to touch on here is the 1967 Chevy Impala that Dean Winchester drives in the TV show Supernatural.

It’s an iconic car, and even if you’re not a fan of Supernatural, it’s hard to ignore the fact that one of the strongest visuals of the show is the dark Impala barreling down a foggy, forested road at night. It’s an aesthetic that fits Dean’s character, but it’s so much more than that.

The History of a Character

The Impala was first introduced in 1958 as a top-of-the-line luxury car for the middle-class, and continued to be a high-end vehicle for most of its history.

Today, the Impala is far from a luxury car. Its reputation has shifted from being a sports car to a utilitarian vehicle, a daily driver for the lower to middle class.

But, the 1967 Impala was something special, and it was certainly unique for Dean. We see the history of the Impala in the last episode of season 5, but the car has more history than the show tells us.

The year 1967 was a tumultuous year for Americans. We were fighting on every front, at home and abroad. Racial segregation, the Vietnam War, and political unrest.

But it was also a year of unprecedented scientific growth. Dr. James Bedford became the first person to be cryonically preserved, NASA was making vast strides with the Lunar Orbiter and Apollo programs, and black holes earned their name.

And the car, the 1967 black Chevy Impala, was born amid this era of intense change. And it would live to see a new era of change, carrying Dean and Sam.

However, it’s not all about violence and science. In 1967, McDonald’s introduced the Big Mac and The Doors released their first album. These events are reflected in Dean’s character, as someone who loves cheeseburgers and rock-n-roll.

In many ways, the idea of the Impala is reflected in Dean’s character, and vice versa. Dean’s penchant for classic American muscle and his practical sensibility convenes in the Impala. The muscle car became Dean’s work car, packed with the tools of his trade, like the modern Impala. But it was a vehicle of change (pun intended), and the prime reason Sam was able to resist Lucifer’s power.

Why Sci Fi Cars Are So Important

Dean Winchester’s Impala is only a single example among hundreds. Sci fi cars and trucks and spaceships and boats, etc. etc. are more than just modes of transport. They’re homes and characters in their own right.

Ingrassia and Will claim that Americans purchase cars to fit their self-image. I’ll go a step further to say that cars help define our self-image. It’s an expression of ourselves, kind of like clothing. We buy things to fit a certain aesthetic, but we also start to bend our aesthetic to the things we already own.

As a science fiction writer, the car must be one of the most powerful tools for building character.

Think about it. The Mystery Machine, Scooby and the gang’s iconic 1978 Volkswagen LT 40, is an important part of each of the characters. It’s Fred’s baby, where Velma works on her science projects, where Daphne keeps her extra clothes and accessories, and it’s where Scooby and Shaggy run to hide, nap, or eat snacks. The van is an important part of each of the characters’ personalities, and is a foil for the writers to express those things.

Imagine the Scooby gang riding in anything other than the van. An F-150 perhaps, or a Volkswagen Bug. It’s not the same. Those cars say something different about the characters.

In Conclusion

This article is far from complete. There are so many more examples we could delve into. The DeLorean, K.I.T.T. and the Batmobile, to name a few.

But in just these few examples we’ve discussed, it’s clear that sci fi cars do far more than get the characters from point A to point B. They’re extensions of themselves just as much as the characters are extensions of their cars.

What sci fi cars do you think hold the same weight as the 1967 Impala? Let us know in the comments down below.

And if you liked this article, you might also enjoy our discussion of Kurt Vonnegut and science fiction.

Galaxy’s Edge Interviews Jonathan Maberry

In the September 2021 issue of Galaxy’s Edge, Jean Marie Ward interviews Jonathan Maberry, prolific writer and editor of Weird Tales magazine.

Check out the full interview below, and if you like this content, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge, where we bring you the best speculative fiction from writers new and old, as well as thoughtful interviews and book reviews.

About Jean Marie Ward

Jean Marie Ward writes fiction, nonfiction and everything in between. Her credits include a multi-award nominated novel, numerous short stories and two popular art books. The former editor of CrescentBlues.com, she is a frequent contributor to Galaxy’s Edge and ConTinual, the convention that never ends. Learn more at JeanMarieWard.com.

Confessions of a High-Output Writer

New York Timesbestselling author Jonathan Maberry credits his grandmother, his middle school librarian, and the college professor he once hated most with turning him into writer. But it’s doubtful they or his former mentors, Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson, could have foreseen how far their lessons would take him. The short list of his honors includes five Bram Stoker Awards, the Inkpot Award, three Scribe Awards, multiple teen book awards, and designation as a Today Top Ten Horror Writer. His many novels and anthologies have been sold to more than thirty countries. As a comics writer, he has written dozens of titles for Marvel Comics, Dark Horse, and IDW Publishing. V-Wars, the shared world anthology series he created for IDW Publishing, has been made into a Netflix series starring Ian Somerhalder, who previously appeared in Lost and The Vampire Diaries. Maberry’s young adult Rot & Ruin series was adapted as a webtoon for cell phones and is in development for film. As if that wasn’t enough, he currently serves as the president of the International Association of Media Tie-In Writers AND as editor of the iconic Weird Tales magazine.

Huffing and puffing to keep up, Galaxy’s Edge talked to Maberry about his origins as a writer, the experiences that shaped him into a multi-genre powerhouse, and the seminal role Black Panther played in his life.

Galaxy’s Edge: You’ve said many times that you always wanted to be a writer. As a young child you made stories up about your toys. What pointed you in the direction of horror?

Jonathan Maberry: My grandmother, who was my favorite blood relative, was basically a grownup version of Luna Lovegood from Harry Potter. She was that person who believed in everything. She believed in what you call “the larger world”—ghosts, goblins, and by extension, things like UFOs and alternate dimensions in the realms of fairy. She believed in everything. She was born on Halloween, and she embraced that. She only had pets that were born on Halloween. In fact, she gave me the very first pet I ever had, my dog Spooker. There’s a picture of him behind me on the wall. [My grandmother] gave him to me because he was born on Halloween.

She got me involved in the spooky stuff. But what’s interesting is, not only did she tell me all the folklore tales and some of the fictional tales of monsters, she encouraged me to read the anthropology, the science, and the commentary on why people believe these things. Even though she was very broad in her belief systems, she felt that there was a connection to our real world. She felt that what we consider to be the supernatural—or the preternatural, or the paranormal (there are different variations)—are all parts of a world we will eventually learn how to measure, and that we only know about one hundredth or 1 percent of what we will eventually know. So, she considered these things to be future science.

From there, I started learning about vampires, werewolves, and all sorts of things. Of course, I started watching the TV shows and the movies, and became hooked on those. I loved the folktales, the fiction, and the nonfiction. In fact, the first couple of books I did on the supernatural were nonfiction, exploring beliefs about the paranormal and supernatural around the world throughout history. I wrote those books because of her and because of the things she’d exposed me to as a kid.

Galaxy’s Edge: This is probably unfair to your hometown, but my mom was from Philadelphia, and I lived in the suburbs from 1969 to 1977. So, I’ve got to ask, how much did living in Philadelphia during Frank Rizzo’s tenure as police commissioner and mayor shape your vision of monsters?

Jonathan Maberry: Well, it didn’t so much shape my vision as monsters as it did shape my vision of a corrupt police state, which may have informed my love of writing thrillers with corrupt officials. [Rizzo] was not only corrupt, he was notoriously and openly corrupt. It was a reinforcement of the same skewed view of how power was used by those in power over those who didn’t have power that I had learned from home. Because I grew up in a very abusive home with a very dictatorial and violent father in a blue-collar neighborhood that was very violent. A lot of abuse.

There were also a lot of people in the neighborhood who were involved in the police department in one way or another. Rizzo was a policeman’s mayor, you know. Not a good policeman’s mayor, but a policeman’s mayor. He would have been a really good mob boss had he been in Chicago in the ’Thirties. It gave me a very jaundiced view of political power. And the fact that for him, it wasn’t even about party. It was just power. He was a manipulative sociopath in power. That’s a pattern we’ve seen elsewhere.

Galaxy’s Edge: Yes, it is. I also wondered what role did observing this abuse of power play in your writerly activism. You’re involved with multiple writers’ organizations. You founded the Philadelphia Liars Club and Writers Coffeehouses across the country specifically to help writers. Was there a connection between the two?

Jonathan Maberry: It was more of an economic thing, because in the neighborhood where I grew up—actually, in my own household—reading was not encouraged. In fact, if we were seen reading a book, the most commonly asked question was, “Are you trying to get above yourself?” My father used to ask that all the time. And of course, the thought I had was, “No, I’m trying to get above you.”

The desire to educate myself out of that environment was really strong. Not only was reading not encouraged, creative expression of that sort was viewed as impractical and something of an insult to people who are hard-working blue-collar stiffs, which is not the case. You rise to the call of your genius. Whatever you feel you do best is what you should try to do. Writing is what I always wanted to do, and I found so many other writers who had been browbeaten by everyone they knew, even well-intentioned family members, because it’s too hard, you’re not gonna make any money, you’re not gonna do this. It’s all this negative propaganda that is parroted at all levels. It comes down from somewhere, but it filters through family, from neighborhood, through high school counselors.

My high school counselor tried to talk me out of being a writer. That neighborhood, that environment, was all about getting out of school, getting into a factory, and paying the bills. That was it, and that’s doom to a writer. I mean, it’s worse than a prison sentence.

I got some unexpected help along the way from incredible writers who I met in most unlikely circumstances, Ray Bradbury and Richard Matheson, in particular. They didn’t need to help me. It was of no actual benefit to them. But they saw someone who was trying to write their way out of where they were and into the future they wanted. And they helped.

As an inspiration, that can’t be beat. So, whenever I had the opportunity to use my position, my connections, my experience, whatever, to help other writers move up and break through the propaganda, break through the self-doubt, into the opportunity to do something worthwhile with their skills, I took it. It’s tied also to a viewpoint that I saw a lot as a kid, but also saw reinforced during the economic downturn of 2008-2009.

There are two camps of writers. One camp seems to feel that if somebody asks you for advice, or a lead, or something, and you give it to them, that means you’re denying it to yourself. That camp feels opportunities are finite, that open doors are finite, that if you help someone else, you’re screwing yourself. It’s a very fear-based viewpoint. It’s also a very popular viewpoint. The other camp believes that if writers help other writers to become better writers, more good books will get written. Those good books will attract more book sales and more readers, and everyone will prosper.

One approach is fear-based, and the other is optimism-based. I’ve always felt that the optimism-based approach is what’s going to get us out of the mud that we’re stuck in when we grow up in an environment like that and have been propagandized like that.

Galaxy’s Edge: Your first fiction series, the Deep Pine Trilogy, drew a lot on the knowledge and love of folklore your grandmother inspired. But your later works, notably, V-Wars and the Joe Ledger series display a profoundly scientific bent. What drew you to blending science and horror?

Jonathan Maberry: Again, that started with my grandmother encouraging me to read the science, the folklore, even the medicine, to explain things. For example, a lot of the beliefs about evil spirits coming to draw the life out of a sleeping child were really ways for less educated people in earlier centuries to explain things like sudden infant death syndrome. If you look at the science of it, you can understand the belief. With that comes also understanding of the needs for [the belief]. I’ll explain with SIDS.

A healthy child goes to bed and dies. There are no marks. There’s nothing to suggest that it was harmed. But maybe the window was open, and people say, “Oh, something got in.”

But say this is the 17th century, and a child died under those circumstances. It feels so arbitrary that it puts people out of sync with their religious beliefs. Why would a loving God allow an innocent child to die like that? So, the parents go to their priest, which was the common thing to do, because the local church was the center of knowledge and where information was shared. The priest says, “Well, you must have sinned in some way, say these prayers, put up these relics, and it won’t happen again.” Sudden infant death syndrome rarely happens again within the same family. So, the next child doesn’t die after the rituals, and the people have a reinforcement of their faith.

Thus the presence of the belief in a monster that has come and taken the life of the child becomes necessary to reinforce their belief in a protective God. Reading the science of that not only gives me a historical and clinical perspective, it gives me real insight into character motivations as needs, and the way in which a story then evolves into a satisfying conclusion.

Galaxy’s Edge: Did meeting Richard Matheson have anything to do with it?

Jonathan Maberry: Richard Matheson is the biggest influence on my style. Even though I write in about a dozen different genres, almost everything I write is built on the structure of a thriller, the race against time to prevent something from happening—as opposed to a suspense, where we’re all in the moment or in a mystery we’re solving. The thriller is that race against time. {Matheson’s] novel, I Am Legend (which he gave me a copy of for Christmas 1973) is a prototypical thriller. I mean, it’s a prototype for the thrillers that came afterwards.

[In I Am Legend] something comes up. A big calamity ends the world. You have the apocalyptic element of the story. You also have a science element to the story because it was the first time that a horror story or the genre of science fiction horror used actual science to try to explain itself.

Prior to that science fiction horror like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde or Frankenstein made references to chemicals or galvanism without going into any detail. In I Am Legend, [Matheson] actually went into the experiments to find bacillus vampiris, which created the vampire plague. He gave us the scientific explanation, the step-by-step. That made it so much more real. The story became more riveting and more threatening to the reader, because now that line between reality and fiction is blurred. That makes it a really compelling thriller.

I’ve taken that model and applied it to almost everything I’ve written. I also use this old con man saying: “Use nine truths to sell one lie.” I build my fiction on a scaffolding of pretty solid science. I do a lot of research, so it’s harder for the reader to know when I have stepped off into fantasy. That started with Matheson and a lot of what Matheson told me when I was a kid.

Galaxy’s Edge: Fifteen-years-old is a very impressionable age, isn’t it?

Jonathan Maberry: Yes.

Galaxy’s Edge: You imprinted on him.

Jonathan Maberry: Well, I met him when I was 12. It was the middle school librarian at my school in Philly who introduced me to him, Bradbury, and others. There was a group of writers who would meet occasionally in New York, and she worked as a kind of informal secretary for them. She dragged me along, partly as baggage and partly because she knew I wanted to write. They took me on as a pet project. All of these great writers, Arthur C. Clarke and Harlan Ellison—whoever was in town—took time to give me advice, like they were competing with one another to give me the best advice that night. I’m really cool with that kind of attention. In fact, the tenth-anniversary edition of Ghost Road Blues, my first novel, has the last ever cover quotes from Bradbury and Matheson.

Galaxy’s Edge: Oh, how wonderful! Now you’re paying forward the help you received.

Jonathan Maberry: Which I should. We should all do that, because there’s not one person who has ever gotten anywhere significant without help. And often, too often, people don’t pause to explain that help was there, who helped them, or to even focus on their own gratitude for what happened. You know, it’s not all about us. It’s literally about us—the community, not the individual. I get so jazzed seeing people take that step, get that deal, or hit a list. It’s like an ongoing party.

Galaxy’s Edge: Returning to the subject of science and pseudoscience, we both grew up in a time when educators and behaviorists believed that growing minds should be shielded from the horrors of things like Weird Tales, EC comics, and Hammer Films. As evidenced by your YA titles, such as the Rot & Ruin series, you see things differently. Why is horror important for young adult readers?

Jonathan Maberry: Because horror is almost always a metaphor for things that are happening in real life. I grew up, as I said, in an abusive household, a very violent household, and a violent neighborhood. There was nobody shielding me as a kid. As a result, I think I got a more clear and well-balanced perspective on life than I would have had if I had been sheltered. Sheltering someone from immediate harm—like pulling your kid away from a hot oven—okay, that’s smart. But not allowing the kid to understand the nature of danger, the nature of heroism, the nature of survival, or all the different qualities that they will need as adults? Sheltering them from that is silly, because it’s not like once they graduate from high school, they suddenly get a download of all these survival skills. They don’t. They have to acquire them along the way.

I remember just talking to my friends as a kid. We were a lot deeper than the adults thought we were. All kids are deeper than adults think they are. To shelter them is a great way to prevent that intellectual growth, empathic growth, and societal awareness. Anytime you shelter, you blind. Anytime you allow the kid to see and then make decisions, and form their own opinions, you’re encouraging growth. It’s useful if parents are there to have conversations about it, but not to stand in the way.

Galaxy’s Edge: You’ve worked extensively in comics, television, and animation. How difficult was it to switch from writing novels and short stories to scripting comics and other broadcast media?

Jonathan Maberry: Well, I haven’t actually written TV scripts yet. I’ve had stuff adapted. I was executive producer, but I was not actually writing the scripts. I haven’t done that yet. I’m studying the form because I will be doing that.

As far as comics go, comics were a bit of a culture shock for me. I mean, I grew up with comics. I was a Marvel kid. I’ve read all the Marvel Comics. But to write them? I write very long novels. My first novel is 148,000 words. It’s a long novel where you can have long conversations with characters, long descriptions, long interior monologues, and so on. But you can’t in comics. Brevity is very important. But also with comics, you have to realize that it is no longer a solo act. With a novel, it’s you and your laptop. With comics, you write the script. You describe what’s in each panel, so you give the art direction. Sure.

But then the artist comes in, and the artist’s A game is to do visual storytelling. You have to learn how to not yield control but share the process, so that they are able to do their best work while you’re doing yours. Then the colorist, and the letterer all have artistic contributions to make. It’s a much more collaborative process. I’ve been told by friends of mine who have gone from comics to writing TV, that it’s excellent training for writing for television, because TV and film are also collaborative. I’m now in the process of pitching a TV series with a couple producer friends, and everything is collaborative. We all have strong ideas, but it’s not one person’s gig. So I learned a lot of that from comics.

One funny thing happened when I just started writing comics. I love dialogue. So I had a lot of dialogue in one of my first comics, and the artist very politely said, “At any point, would you like the readers to be able to see the art?” And I’m like, “Oops.”

It’s funny, I had already been warned about that by Joe Hill, who is the son of Stephen King, and a great writer himself. [Hill] had had almost exactly the same conversation with Gabriel Rodriguez, who was his artist for Locke & Key. Joe said, “Do your draft, and then cut it back by 80 percent.” And I’m thinking, “I don’t need to do that.” Then I got that email, and it was: “Oh, yeah, I need to do that.” The comic was better for it, by the way…

Friends of mine, like Gregg Hurwitz, who wrote Batman and a lot of TV, said, “Writing an issue of comics is very similar to writing an hour of TV drama.” Even the beats are the same, because you have to have dramatic beats for ads and page breaks, which are not that dissimilar from the beats for commercial breaks. He said, “It’s about 75 percent. If you can write a comic book, you’re 75 percent there for how to write a TV script.”

Galaxy’s Edge: Speaking of comics, I didn’t realize when I was drafting my questions that the way you got involved with the Black Panther comic was among the most important events of your life, both in terms of your introduction to the comic, and later in terms of writing it. Would you mind talking a little bit about that?

Jonathan Maberry: When I was a kid, I got involved in Marvel Comics in a big way. I was really a huge fan of Marvel, my favorite comic being The Fantastic Four. The character of the child of the Black Panther was introduced in one of the early issues. I think it was issue 54 of Fantastic Four.

My father, who was deeply racist and involved in the Ku Klux Klan, was very upset that I was reading a comic in which a black man was a king, a superhero, and a scientist. He tore the comic up. He knocked me around for even having it. But a couple of years later, I took another issue of that comic in which the Black Panther appeared to my middle school librarian, the same one introduced me to Matheson and Bradbury. I said, “I’d get in trouble if I show this to my father. Can [you] tell me about this?” And she said, “Well, that particular issue is about apartheid.” I had no idea what that was.

[I showed her] another issue that I brought with me, and she said, “That one’s about the Jim Crow laws.” She kept asking me if I knew about these things, and I didn’t, because all that had been suppressed in my neighborhood. I met no one of color until I was in seventh grade, not one person. I wound up diving deep into an understanding of racism and intolerance. As much as Philadelphia is the City of Brotherly Love, there was a lot of racism there. In certain parts of the city, it was pretty intense, especially in the ’Sixties. That understanding opened my eyes. You know, you have a choice. You can close your eyes and pretend the world is what you were trained to believe, or you can keep your eyes open to see the world for what it actually is.

I don’t believe in closing one’s eyes. The old nature versus nurture thing is actually an imperfect equation. It’s nature versus nurture, versus choice. Choice is a big thing. I chose to keep my eyes open.

I went diving deep into understanding racism. It changed the course of my life and split me from my father forever. Every part of my personality, every part of my understanding of the world and fairness and everything of history pivoted on that moment. It is the most important single moment of my life.

Roll forward to 2008-2009. I had just started writing for Marvel Comics, and Reginald Hudlin who is the founder of BET, an Academy Award-winning producer, and was then the writer of Black Panther, heard this anecdote. He suggested to the editor-in-chief of Marvel that when he stepped down, they have me write the comic.

Now, this was a challenge. At this point, Black writers were writing the Black Panther comic, and I agree with having Black writers write that comic. It’s the iconic, first Black superhero ever. But that child had saved my life too. It had changed me. Just as it changed the lives of a lot of Black kids who found that character, it changed my life as a White kid who found the character. And they asked me if I would write a comic which, of course, I wanted to write. I actually cried when I was told that they were offering this to me.

But also, because I had been teaching women’s self-defense for so many years, including 14 years at Temple University, they made a change in the character. T’Challa got injured in the comic, and his sister Shuri had to step up to become the Panther. So what they handed me was the feminist Black Panther comic to write, which I did for two years. It was one of the greatest honors of my career, and so much fun. And I’m pretty sure that my father was spinning in his grave at warp speed because this was everything he would have hated, and it’s everything that I became because that character help split me off from him.

It’s one of my favorite memories, and one of my favorite things to say is: “Yeah, I was part of that actual world. I was part of the Black Panther. I have my own guest membership in Wakanda.”

Galaxy’s Edge: Amazing. Simply amazing. You never know where the words you put on the page will take someone you never met.

That’s an impossible act to follow, but I do have a couple of questions left. With all the articles, books, comics, greeting cards, and everything else you’ve written, what prompted you to add editing to your resume?

Jonathan Maberry: When I got into novels, which was only 2006, I thought that was all I was gonna do. I had no interest in writing short stories. Then I was invited to write a couple of short stories for different anthologies. I liked the process, but I generally do not do a project unless I become familiar with the other players. So, I started having conversations with the editors, getting insights into what they do and seeing how much they loved it. You know, they’re the first people to read stories [they’ve commissioned] by their favorite writers. I said, that sounds like Christmas morning.

So, I started putting out feelers. But the way I started editing my World War Z anthologies was kind of funny. Max Brooks had been editing an anthology of G.I. Joe stories—the little Hasbro toys. He invited me to write a novella for it, which I did. He had originally planned to do a couple of different anthologies for that same publisher, IDW Publishing. But after [the G.I. Joe] project, he had to go and do something else.

So IDW asked me if I would like to edit the next anthology. I had just finished reading a whole bunch of shared world anthologies, and I thought, “Wow, that’s kind of fun. If I’m gonna do one, I might as well do one where I can play too.” Generally, the editor of an anthology does not contribute a story. But in a shared world, they usually create the world, write a framing story, and other people write individual stories.

So, I pitched one about a plague that turns people into vampires. It became V-Wars, my first anthology, and I loved it. I curated it. I invited those friends of mine who were really good writers, but who were also of the same emotional bent as me in that I felt they were good-hearted people, people who were generous with their colleagues, especially with newer colleagues, and played well with others. I do not work with people who are prima donnas. It’s just not worth the effort. I want people who are having fun but also professional. I fell in love with them.

I’ve edited 18 anthologies. Then later on, a producer friend, who was involved in the return of Weird Tales magazine, asked if would I be interested in coming aboard to help curate and edit some issues. I started out as consulting editor or editorial director—I think that was the first title. But by the second issue, I was actually the editor. And well, I’m working with my next two issues simultaneously.

Galaxy’s Edge: That is a heavy workload. Anything related to a periodical is a full-time job.

Jonathan Maberry: Yeah, but I had really interesting training. I went to Temple University School of Journalism, and I had a couple of teachers, notably John Hayes, who was a teacher I hated while at school, and now I wanna put him up for sainthood. He taught me how to be a high-output writer, which is a skill set. I didn’t know I would like to do that. Turns out it’s where I’m having the most fun. I wouldn’t have taken on the editorial gigs had I not felt that I could work them into my schedule while still writing three to four novels a year and short stories. I’m having a blast doing it. Yeah, it makes for some long days sometimes, but it’s a long day doing what you love. It’s not like it’s a hardship.

Galaxy’s Edge: We’re coming up on the end of the interview. Is there anything you’d like to add?

Jonathan Maberry: For any writer out there who’s reading this, the Writers Coffeehouse has, because of COVID, moved online. You can find us on Facebook at Facebook.com/groups/TheWritersCoffeehouse. It is free. It is a community of writers helping each other with no agenda other than to help each other. So go check it out on Facebook. Also, if you go to my website, JonathanMaberry.com (only one “Y”), there’s a whole page of free stuff for writers—comic book scripts, novels, samples, and so on. It’s all downloadable PDFs. Go grab what you need.

Copyright © 2021 by Jean Marie Ward.

Like our interviews? Read our conversation with qntm, author of There Is No Antimemetics Division and author Seanan McGuire!

Science Fiction Awards Not Everyone Knows

We’ve all heard of the Hugos and the Nebulas. They’re the big names when it comes to science fiction awards.

And while having a Hugo or a Nebula is a great achievement, there are plenty of other reputable awards for science fiction books (and short stories and poetry) out there too.

Here are a few science fiction awards not everyone knows about!

- Gaylactic Spectrum Award

- Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award

- Dwarf Stars Award

- Eugie Award

Gaylactic Spectrum Award

The Gaylactic Spectrum Awards were initially presented by the Gaylactic Network, first established in 1998 and first awarded in 1999. However, they created their own organization in 2002 called the Gaylactic Spectrum Awards Foundation.

The award focuses on works of sci-fi, horror, and fantasy that positively represent the LGBTQ+ community.

Categories

They have award categories for Best Novel, Best Short Fiction, and many others.

Previous Winners

Nicola Griffith won three awards, making her the most awarded novelist in of the GSA. She has also been given five nominations, alongside Melissa Scott, making them both the most nominated writers in this spectrum.

If you’d like to nominate a piece for this science fiction award, please visit their website.

Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award

The Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award was created in 2001 by the Cordwainer Smith Foundation in memory of science fiction author, Cordwainer Smith.

Cordwainer Smith was a pen-name for Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, a former US Army officer and expert in psychological warfare. He wrote a number of science fiction novels, but his career was cut short in 1966, when he suffered a heart attack.

His memorial award focuses on under read science fiction or fantasy to purposely draw more attention to the authors.

Categories

The awards go to Best Underrated Science Fiction and Best Underread Fantasy.

Previous Winners

British writer and philosopher Olaf Stapledon was the first winner of the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Awards, and since 2001, the awards haven’t stopped. Most recently, British writer David Guy Compton (or D. G. Compton) won the last award in 2021.

Other previous winners were:

- R. A Lafferty (2002);

- Edgar Pangborn (2003);

- Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore (2004);

- Leigh Brackett (2005);

- William Hope Hodgson (2006);

- Daniel F. Galouye (2007)

- Stanley G. Weinbaum (2008)

- A. Merritt (2009), Mark Clifton (2010);

- Katherine MacLean (2011);

- Fredric Brown (2012);

- Wyman Guin (2013);

- Mildred Clingerman (2014);

- Clark Ashton Smith (2015);

- Judith Merril (2016);

- Seabury Quinn (2017);

- Frank M. Robinson (2018)

- Carol Emshwiller (2019); and,

- Rick Raphael (2020).

Dwarf Stars Award

The Dwarf Stars Award was established as a counterpoint to the Rhysling Award in 2006, both awards given by the Science Fiction Poetry Association. Dwarf Star was created to honor short form poetry, as many of the winners of the Rhysling award wrote in long forms.

This award focuses on sci-fi, horror, and fantasy poems of ten lines or fewer, published in English in the prior year.

Categories

Categories include Best Science Fiction Author, Best Horror Author, and Best Fantasy Author.

Previous Winners

The awards have first, second and third places. American writer Ruth Berman won first place in 2006, and John C. Mannone won first place in 2020 (the last award given so far).

Other previous first-winners include: Jane Yolen (2007), Greg Beatty (2008), Geoffrey A. Landis (2009), Howard V. Hendrix (2010), Julie Bloss Kelsey (2011), Marge Simon (2012), Deborah P. Kolodji (2013), Mat Joiner (2014), Greg Schwartz (2015), Stacy Balkun (2016), LeRoy Gorman (2017), Kath Abela Wilson (2018), and Sofia Rhei (2019).

Eugie Award

The Eugie Foster Memorial Award (or simply Eugie Award) was first presented in 2016 at Dragon Con’s awards banquet and has been ongoing ever since. It was named in honor of prolific speculative writer and editor Eugie Foster.

This award focuses on short speculative fiction published in the previous year.

Categories

The Eugie Award categories include Best Innovative and Essential Short Speculative Fiction.

Previous Winners

The American writer Catherynne M. Valente won the first award back in 2016, and the Canadian writer Siobhan Carroll won the last award in 2020.

Other previous first-winners include N. K. Jemisin (2017), Fran Wilde (2018), and Simone Heller (2019).

There are plenty more science fiction awards out there, some well-known, some a bit more niche. Is there an award that you follow closely? Comment down below!

And if you’re interested in the Mike Resnick Memorial Award for Short Fiction, you can check out the guidelines here:

The Importance of Music in Afrofuturist Literature

Continuing our series on science fiction genres, this week we’re talking about Afrofuturism.

What is afrofuturism? Afrofuturist literature spans across numerous genres, including science fiction, fantasy, horror, and alternate history, to name a few. It often pairs technology with cultural elements from the African diaspora. Popular authors within the movement include Colson Whitehead, Nnedi Okorafor, and Samuel R. Delany.

Afrofuturism is one of the few genres that full transcends boundaries of form, working its way into film, music, and other visual arts.

Speaking of music, one of the most prominent themes of Afrofuturist literature is the incorporation of music as a central, binding element. It appears in literature as a callback to a cultural past, and as a glimpse into the future.

Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany

One of Samuel R. Delany’s earlier works of science fiction, Empire Star presents the journey of a young agricultural worker, Jo, as he crosses the galaxy to deliver a message. Along the way, Jo begins to refine his “simplex” mind into what Delany calls a “multiplex being,” which is essentially being able to operate on an intellectual level where one answers the question before it is asked, essentially a heightened form of analytical and literary thought.

Delany experiments with point of view and chronology, ultimately revealing that the whole story was a progression of an ever-expanding timeline. He grapples with the remnants of slavery, both physically and intellectually, and brushes on the harsh powers of colonialism that keep people of color down using economics and education as leverage.

And yet, atop all of this heavy, thematic commentary, Delany still manages to show that music is a critical element in this world.

image from Wikipedia

Early on, one of the characters that Jo encounters takes him to see the Lll, which are the slaves of the empire, builders of beautiful buildings. As a shuttle-bum, Jo’s job is to play music and soothe these creatures, who emanate powerful sadness that makes Jo cry.

Jo is told that playing the music will make the Lll happy, but he will not feel any better. And, to elaborate upon his point if he was not clear, Delany shows us later in the story, when another character tells Jo that “singing is the most important thing there is”.

For Delany, it is clear that music plays an important role in the preservation of culture and its ability to uplift spirits holds a special place in his writing. The Lll, the oppressed builders, are analogous to plantation slaves in the American south who sang spirituals and cultural songs to keep their hopes up and help cope with their situation. Even in a multiplex future, music is still used as a powerful cultural tool, and Delany incorporates it to indicate its transcendence through our past, our present, and our future.

The Afrofuturist Music of Jimi Hendrix & Kid Cudi

In 1967, Jimi Hendrix released “Purple Haze,” the song that took him to fame. He was inspired by years of reading science fiction and an UFO that he saw as a kid. The song was originally about the “history of the wars on Neptune” and was well over a thousand words long. For Hendrix, writing songs was his way of contributing to the science-fiction community and recognizing his Afrofuturism, and inspiring future artists.

Since the times of Jimi Hendrix, Mothership Connection, and Planet Rock, Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic Force, Afrofuturism has persisted in music. In 2014, Kid Cudi released his Satellite Flight album, which is based heavily upon ideas of living on the moon and space travel while also retaining the social activism that Kid Cudi puts in all his music.

Cudi presents the idea that space is a place away from earthly restrictions, saying that he wants to take his “vibe” to a place where “there aren’t any roads” and where the haters “can’t follow.” In this way, space is an escape and a new horizon, a sentiment expressed across numerous Afrofuturist texts.

Rhythm Travel by Amiri Baraka

This story is a good one to conclude with, as it seems to pull together many of the threads that have been developing in this discussion of Afrofuturist literature and music. Written by Amiri Baraka in 1996, “Rhythm Travel” is a conversation between two characters, one of which is describing a method of time traveling based on music.

At one point in the story, the rhythm scientist, we shall call him, materializes in front of the other character, using certain rhythms to become “dis visible”.

Now, the idea of dis visibility is different than invisibility, and the scientist even makes a point of referencing Invisible Man and its author, Ralph Ellison. In this context, dis visibility is the ability to remove oneself from unwanted attention, to disappear and reappear at will, whereas invisibility, as Ellison might describe it, is to be unseen at all points, whether wanted or unwanted.

But what is it that allows the rhythm scientist to be dis visible? Music, of course.

This piece illustrates that intense power that music has for the black community, where it helps them avoid the oppression of the system and skirt the imbalance of power. Music here demonstrates a deep historical connection to survival, and has embodied that in the work of the rhythm scientist.

In Conclusion

From novels to rap, we’ve seen Afrofuturist literature at play with music in various ways. As an expression of desire to be understood and removed from an overly-critical environment, and as a deep-seeded cultural heritage used as a means of protection.

Music’s power as an element of change and vocal expression is a large part of the Afrofuturism movement, and there are hundreds of examples beyond these, so I encourage you to go out and find them, make the connection between literature and music, and find the many-faceted meanings of that connection.