An award-winning author, and a regular to the pages of Galaxy’s Edge Magazine, writer and editor Mica Scotti Kole gave us the chance to peal back the pages and get a glimpse inside the life of a dreamer, artist, and someone who has followed her dreams straight into a reality …

Continue reading “Interview with Author Mica Scotti Kole”Category: Publishing

10 New Sci Fi Books To Read This Summer

With the height of summer right around the corner, it’s time to pad out your reading list for the weekend beach trips and lazy backyard afternoons.

Thankfully, there’s no lack of new sci fi books coming out this summer, so you’ll have plenty to keep you busy.

The City Inside by Samit Basu – June 7th

In near future Delhi, Joey works as a Reality Controller for one of the city’s biggest reality stars. Rudra lives on the other end of the spectrum, in an impoverished neighborhood, estranged from his family.

When Joey offers Rudra a job, they’re both thrust into a world of complex loyalties, capitalism, and toxic relationships.

Lavie Tidhar, a World Fantasy Award winner, says, “The City Inside is a triumphant exploration of near-future India that is as compelling as it is urgent. Don’t miss this one.”

The Splendid City by Karen Heuler – June 14th

Eleanor lives in the state of Liberty, which is not as free as it might sound. When a witch disappears from a local coven, Eleanor believes it could be linked to the water shortage in Liberty.

Along with her ex-co-worker-turned-cat Stan, Eleanor embarks on a quest to get to the bottom of Liberty’s dark secrets.

“The dialogue is clever and the satire spot-on. The social commentary hits the nail on the head.”

– Booklist

Drunk on All Your Strange New Words by Eddie Robson – June 28th

Lydia works as a translator for an alien ambassador to Earth, putting into words his thoughts and feelings. But, as tragedy strikes, Lydia is thrown into an intergalactic incident with no end in sight. She has to muster her strength and use her skills to prove her innocence.

“Drunk on all Your Strange New Words is a twisted murder investigation through a post-contact future full of world-building in fascinating detail.” ―Django Wexler

The Moonday Letters by Emmi Itäranta – July 5th

Sol has gone missing, and their wife Lumi must start the search. As she works her way closer to Sol, she uncovers the secrets of eco-activists and Sol’s past. Lumi travels from the colonies of Mars to the devastated Earth in search of Sol.

This book is part epistolary mystery, part eco-thriller.

“Where Itäranta shines is in her understated but compelling characters.” – Red Star Review, Publishers Weekly

Upgrade by Blake Crouch – July 12th

Crouch is well on his way to becoming the next William Gibson, and Upgrade is right in line with that trajectory.

This new novel is about Logan Ramsay, a wayward science experiment who may be the only person who can set the world straight.

Andy Weir said about the book “Walks the fine line between page-turning thriller and smart sci-fi. Another killer read from Blake.”

The Daughter of Doctor Moreau by Silvia Moreno-Garcia – July 19th

Carlota is the only daughter of Doctor Moreau, and she lives side-by-side with his hybrid experiments. Her whole world is shaken up when the son of her father’s benefactor comes to their estate.

This book is a historical novel, a romance, and a science fiction novel.

Booklist says this book, “As alluring as it is unsettling, filled with action romance, and monsters . . . Readers will fall into this tale immediately, enchanted.”

Just Like Home by Sarah Gailey – July 19th

Gailey’s back at it with another gothic horror novel, this time focusing on Vera, a young girl returning to a home that houses a serial killer.

A “parasitic artist” resides at Vera’s house now, and Vera’s not sure whether or not he’s the one leaving messages in her father’s hand writing.

“Gailey’s newest gothic novel is painfully suspenseful and richly dark, their rushing, intoxicating writing in peak form. Delightfully creepy and heartbreakingly tragic, Just Like Home is equal parts raw terror of a dark childhood bedroom, creeping revelations of a true-crime podcast, and searing hurt of resentment within a family. It’s a must-read for all gothic horror fans.” ―Booklist, starred review

Eversion by Alastair Reynolds – August 2nd

Dr. Silas Coade, a physician for an exploratory space voyage, realizes that he alone can save the crew from a dangerous fate. A fate that had been foretolds since the 1800s, in an exploration that Coade was also a part of.

This book bends the fabric of time and space with a dark twist.

“Pirates in space, full of peril and high-jinks… This is a novel that’s elegantly plotted, full of surprises and, as first time round, rip-roaring fun.” – SFX Magazine

The Sleepless by Victor Manibo – August 23rd

Jamie Vega works as a journalist until his boss mysteriously dies during a corporate merger. Vega’s the last person to have seen his boss, but can’t quite remember it.

He becomes subject of a murder investigation and Vega dives deeper into what it means to be Sleepless, coming toe-to-toe with brutal crime organizations and corporate lawyers.

“The Sleepless is just the beginning; Victor Manibo is an author to keep your eye on.” —Lara Elena Donnelly, author of The Amberlough Dossier and Base Notes

Babel by R.F. Kuang – August 23rd

Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence: An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution is about the balance of power and the promise of revolution.

A young Chinese boy, Robert Swift, is raised in England and prepared to attend the Royal Institute of Translation. This school is dedicated to imperial expansion, and uses magic to help reach the English agenda.

Rebecca Roanhorse, author of Black Sun, says “R. F. Kuang has written a masterpiece.”

Breaking Up The Story: What is Serialized Fiction?

In many ways, the Internet completely changed how we look at fiction. What was once a very tangible thing—think magazines, books, newspapers, etc.—has become somewhat immaterial. You can’t hold a magazine issue digitally; you’re holding your phone or tablet, and it’s just not the same.

If you didn’t have a subscription to your favorite science fiction magazines back then, you could head to the library, borrow a friend’s or check out the corner store.

Now, it seems that physical magazine subscriptions are few and far between. Why pay for a tangible thing when you can save money by reading the stuff online for a fraction of the cost, sometimes for free?

That paradigm shift comes with its own quirks. If you happen to forget to bookmark a short story you read in some magazine, it might be completely lost to you if you end up forgetting author, title, and place of publication.

If you had the magazine on your shelf, all you had to do was flick through until you found it. Now you have to scroll through the archives, opening a thousand tabs to find the story. Or worse, attempt to prod the collective mind on Reddit or Twitter.

However, one of the interesting things about the relationship between the Internet and fiction is serialized fiction, which is a format that predates the Internet, but has gotten so much more traction because of it.

What is Serialized Fiction?

Serial fiction, or serialized fiction, is when a longer work is broken up into smaller installments that are released on a set schedule. Think TV episodes, but for fiction.

Where do serials appear? They can pop up in monthly, bi-monthly, weekly, or daily publications, like magazines or newspapers. Not only is serialized fiction a great way for authors to keep interest in their work going for a long time, it’s also used as a tool to sell more magazines or newspapers. If people get invested in the serial, they’re going to have to keep buying to read!

Serialized fiction is by no means a new concept. It’s been around for hundreds of years, and picked up popularity when the printing press made reading material more readily available for people outside of the aristocracy.

Charles Dickens had Great Expectations serialized in 1860, and Arthur Conan Doyle wrote many of the Sherlock Holmes stories to appear sequentially in various magazines.

Fast forward a hundred years, radio and television drastically changed the world of serialized fiction, bringing a more lifelike element to it. Even comic books work on the same principle as early serialized specials.

But what about today? And what about SFF publications? Where do they stand?

Serialized Fiction in 2022

The Internet has made writing fiction like Charles Dickens did nearly impossible. Sometimes, scenes in Dickens’ novels stretch for pages at a time, barely broken by dialogue or action of any kind. Unless you’re hyper-focused on the text, it’s difficult to read it without drifting off into daydreams or switching to a more engaging activity.

And we have the Internet and social media to blame for a lot of that. Recent studies have shown that the human attention span is about 8 seconds, which is why so many videos on Instagram and TikTok are limited to under 60 seconds. Anything longer, people just won’t watch it.

Even the way we have to format writing has changed. Gone are the long paragraphs, which were replaced with white space every two or three sentences.

So, it was only natural that serialized fiction would make an appearance in the new digital world. The bite-sized installments are easy to handle, and fit into even the busiest schedules.

Ways to Read (and Listen)

Now, more than ever, serialized science fiction and fantasy works are on the rise. Serial Box, which has since become Realm, features episodic fiction from authors like Max Gladston, K. Arsenault Rivera, E.C. Meyers, Yoon Ha Lee, Mary Robinette Kowal, and so many more.

Realm offers readers multiple installments of the same story in podcast format. Generally, each episode is about an hour and a half long, which makes it easy to find a stopping point.

However, the contrast between the 8 second attention span and the 1.5 hr episode length is pretty distinct.

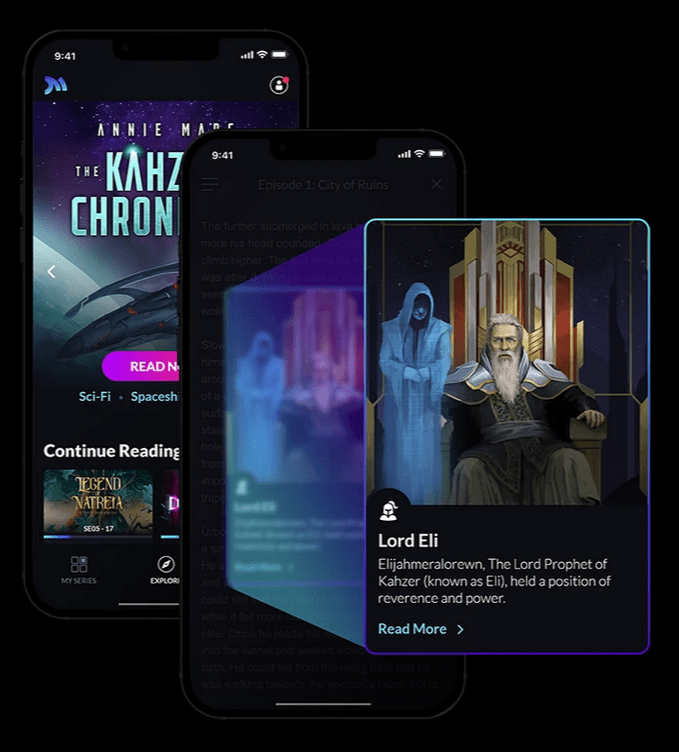

Other serialized fiction platforms, like Mythrill Fiction, break stories down into much more manageable chunks.

On their app, Mythrill has a handful of different stories, ranging in themes from pirates and sea monsters to cyberpunk cities.

Each story is broken up into 20 episodes, with each episode taking about 5 minutes to read.

But, the really interesting thing about Mythrill is their lore cards. These story add-ons help readers quickly get a grasp of the characters and the world, and each come with an illustration.

There are also many serialized fiction podcasts out there, similar to Realm, that have continuous stories that are released in episode installments. Check out our article on SFF podcasts to learn more.

Conclusion

Why do I think serialized fiction is the way we’re going to be reading and listening to SFF in the future? It’s tailored to the current human experience. It might sound dumb, but having fiction that fits into your lifestyle—almost like how Duolingo makes language-learning manageable—is the key to garnering a following.

Don’t get me wrong, I love big books. The Stormlight Archive, Dandelion Dynasty, The Wheel of Time, etc., but more and more I find myself daunted by the sheer size of them.

Who knows, I might be wrong, but now, I see serialized fiction becoming much more popular in the coming years simply because it formats its content in ways we’re accustomed to consuming Internet media.

What are your thoughts? Let us know in the comments below.

Nebula Award 2021 Nominations

It’s that time of year again! SFWA just announced all the nominations for the Nebula Award 2021.

All finalists had their science fiction, horror, or fantasy work published in 2021, and the winners for each category will be announced on Saturday, May 21, 2022 during a virtual ceremony. Eligible SFWA members will be able to start voting on March 14th, 2022.

We are super excited to share that Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki’s story, “O2 Arena”, that was published in Galaxy’s Edge issue 53 last year is a finalist for the Nebula Award for Novelette!

If you would like to read his novelette, you can do so here.

We also provided links to read all of the work that has been published online. Without further ado, here are all the Nebula Award Finalists for 2021:

Best Novel

- The Unbroken, C.L. Clark (Orbit US; Orbit UK)

- A Master of Djinn, P. Djèlí Clark (Tordotcom; Orbit UK)

- Machinehood, S.B. Divya (Saga)

- A Desolation Called Peace, Arkady Martine (Tor; Tor UK)

- Plague Birds, Jason Sanford (Apex)

Best Novella

- A Psalm for the Wild-Built, Becky Chambers (Tordotcom)

- Fireheart Tiger, Aliette de Bodard (Tordotcom)

- And What Can We Offer You Tonight, Premee Mohamed (Neon Hemlock)

- Sun-Daughters, Sea-Daughters, Aimee Ogden (Tordotcom)

- Flowers for the Sea, Zin E. Rocklyn (Tordotcom)

- The Necessity of Stars, E. Catherine Tobler (Neon Hemlock)

- “The Giants of the Violet Sea“, Eugenia Triantafyllou (Uncanny 9–10/21)

Best Novelette

- “O2 Arena“, Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki (Galaxy’s Edge 11/21)

- “Just Enough Rain“, PH Lee (Giganotosaurus 5/21)

- “(emet)“, Lauren Ring (F&SF 7–8/21)

- “That Story Isn’t the Story“, John Wiswell (Uncanny 11–12/21)

- “Colors of the Immortal Palette“, Caroline M. Yoachim (Uncanny 3–4/21)

Best Short Story

- “Mr. Death“, Alix E. Harrow (Apex 2/21)

- “Proof by Induction“, José Pablo Iriarte (Uncanny 5–6/21)

- “Let All the Children Boogie“, Sam J. Miller (Tor.com 1/6/21)

- “Laughter Among the Trees“, Suzan Palumbo (The Dark 2/21)

- “Where Oaken Hearts Do Gather“, Sarah Pinsker (Uncanny 3–4/21)

- “For Lack of a Bed“, John Wiswell (Diabolical Plots 4/21)

Andre Norton Nebula Award for Middle Grade & Young Adult Fiction

- Victories Greater Than Death, Charlie Jane Anders (Tor Teen; Titan)

- Thornwood, Leah Cypess (Delacorte)

- Redemptor, Jordan Ifueko (Amulet; Hot Key)

- A Snake Falls to Earth, Darcie Little Badger (Levine Querido)

- Root Magic, Eden Royce (Walden Pond)

- Iron Widow, Xiran Jay Zhao (Penguin Teen; Rock the Boat)

Ray Bradbury Nebula Award for Outstanding Dramatic Presentation

- Encanto, Charise Castro Smith, Jared Bush, Byron Howard, Jason Hand, Nancy Kruse, Lin-Manuel Miranda (Walt Disney Animation Studios, Walt Disney Pictures)

- The Green Knight, David Lowery (Sailor Bear, BRON Studios, A24)

- Loki: Season 1, Bisha K. Ali, Elissa Karasik, Eric Martin, Michael Waldron, Tom Kauffman, Jess Dweck (Marvel Studios)

- Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, Dave Callaham, Destin Daniel Cretton, Andrew Lanham (Walt Disney Pictures, Marvel Studios)

- Space Sweepers, Jo Sung-hee 조성희 (Bidangil Pictures)

- WandaVision: Season 1, Peter Cameron, Mackenzie Dohr, Laura Donney, Bobak Esfarjani, Megan McDonnell, Jac Schaeffer, Cameron Squires, Gretchen Enders, Chuck Hayward (Marvel Studios)

- What We Do in the Shadows: Season 3, Jake Bender, Zach Dunn, Shana Gohd, Sam Johnson, Chris Marcil, William Meny, Sarah Naftalis, Stefani Robinson, Marika Sawyer, Paul Simms, Lauren Wells (FX Productions, Two Canoes Pictures, 343 Incorporated, FX Network)

Nebula Award for Game Writing

- Coyote & Crow, Connor Alexander, William McKay, Weyodi Oldbear, Derek Pounds, Nico Albert, Riana Elliott, Diogo Nogueira, William Thompson (Coyote & Crow, LLC.)

- Gramma’s Hand, Balogun Ojetade (Balogun Ojetade, Roaring Lion Productions)

- Thirsty Sword Lesbians, April Kit Walsh, Whitney Delagio, Dominique Dickey, Jonaya Kemper, Alexis Sara, Rae Nedjadi (Evil Hat Games)

- Wanderhome, Jay Dragon (Possum Creek Games)

- Wildermyth, Nate Austin, Anne Austin (Worldwalker Games, LLC, Whisper Games)

Congratulations to all of the finalists! 2021 was truly a great year for science fiction, fantasy, and horror. We’re looking forward to seeing the results in May!

If you read “O2 Arena” by Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and you want to read more from Galaxy’s Edge, consider becoming a subscriber:

Science Fiction Anthologies To Watch For in 2022

With the new year fast approaching, there’s a whole new lineup of science fiction anthologies to get excited about.

Personally, I find that science fiction anthologies are the best of both the novel and short story worlds. You get the thick book like a novel, but you get dozens of individual stories, some connected by theme or place and time.

In this blog, we’ll run down some of the newest science fiction anthologies coming our way in 2022.

The Way Spring Arrives and Other Stories

This anthology is a collection of translated short stories from Chinese SFF writers. They focus heavily on fiction from female and nonbinary writers, and the team behind the anthology has a long history in the genre.

Regina Kanyu Wang, one of the editors, has frequently appeared in Clarkesworld Magazine, was featured in Ken Liu’s Broken Stars anthology, and had a story published in the March 2018 issue of Galaxy’s Edge Magazine.

Yu Chen, the other editor of this science fiction anthology, has also been involved in the SFF community for a long time. She’s presented at workshops, conventions, and published multiple books from Asian sci-fi writers like Han Song and Song Mingwei.

I’m looking forward to this anthology, and will definitely grab it on release day, March 8th, 2022.

The Best Science Fiction of the Year

I always look forward to Neil Clarke’s anthologies. His collection of the best science fiction short stories always boasts some of the year’s most intriguing, thoughtful pieces from new and established writers alike.

This will be the sixth anthology in the best of the year series, featuring stories from Yoon Ha Lee, Annalee Newitz, Rich Larson, and Ann Leckie, to name a few.

This science fiction anthology will hit shelves on January 25th, 2020.

Triangulation: Energy

Triangulation is one of the oldest science fiction anthologies that I know of. They started publishing spec fic short stories in the early 2000s, and have kept up the yearly tradition ever since. Each issue has a specific theme, and for the past few years they’ve covered sustainability topics like light pollution, eco-friendly housing, and biodiversity.

This year’s anthology will feature stories about sustainable energy, and all that that encompasses.

While there isn’t an exact date for the anthology yet, they are usually released at the end of the summer.

Check out the interview we did with Diane Turnshek and John Thompson, the editors of the 2021 anthology, Triangulation: Habitats.

The Reinvented Heart

This anthology is edited by Cat Rambo and Jennifer Brozek, and seeks to explore emotional relationships in science fiction.

So much of sci fi is caught up in the physical tech, and often overlooks emotional responses to those same technologies. This science fiction anthology is filled with stories and poems about “how shifting technology may affect social attitudes and practices.”

The anthology features work from Jane Yolen, Seanan McGuire, Ana Maria Curtis, Aimee Ogden and more!

Watch out for this anthology on March 10th, 2022.

Orpheus + Eurydice Unbound

This speculative fiction anthology is expected to release in the summer of 2022 from Air and Nothingness Press.

The anthology will feature stories that re-imagine the Orpheus and Eurydice story from Greek mythology. The book will consist of four sections, with stories that fit each step of the mythological tale, including The Wedding, The Snake, The Quest, and The Look Back.

The theme seems to be fairly narrow, but I have confidence that it will be an exception anthology. Air and Nothingness Press has a reputation for putting out great books, and this one should be no different.

Professor Feif’s Compleat Pocket Guide to Xenobiology for the Galactic Traveler on the Move

This one seems super fun! Dedicated to all flora and fauna of the alien worlds, as far flung as they may be, this anthology is bound to be filled with interesting stories of carnivorous plants, oozing goop, and other weird things.

This science fiction anthology from Jay Henge Publishing has yet to get a solid release date, but I assume it will appear sometime in 2022. Jay Henge has published numerous science fiction anthologies, including Sunshine Superhighway, Sensory Perceptions, and The Chorochronos Archives.

What sci fi anthologies are you excited for? Let us know in the comments below!

And if you’re looking for a New Year’s gift, nothing is better than a subscription to Galaxy’s Edge!

Author Interview with Tristan Beiter: Understanding Speculative Poetry

Recently, I’ve had the pleasure of talking to Tristan Beiter, a rising star in the world of speculative poetry.

I’ve been following Tristan’s journey as a poet for a few years, and had a chance to ask him about his thoughts on speculative poetry as a genre, his favorite poets, as well as his upcoming work.

Author Bio:

Tristan Beiter is a speculative poet originally from Central Pennsylvania now living in Rhode Island. He holds a BA in English Literature and Gender and Sexuality Studies from Swarthmore College and an MA in the Humanities (emphasis in Poetry and Poetics) from the University of Chicago.

His work can be found in such venues as Abyss & Apex, Fantasy Magazine, Liminality, Bird’s Thumb and others. When not reading or writing, he can be found doing needlecrafts, crafting absurdities with his boyfriend, or shouting about literary theory. Find him on Twitter at @TristanBeiter

Isaac Payne: A lot of people have different definitions of speculative poetry, and some consider it to not even be a genre, as the nature of poetry is so non-linear and experimental that all poetry could come off as speculative. What does speculative poetry mean to you?

Tristan Beiter: That’s a great question. I’m sure there are panels I haven’t read, but I’ve read all of the discussions I have been able to find about what is spec poetry. These include the panels in Strange Horizons and a bunch of blog posts on the topic. This was a main issue during my Master’s thesis, it’s “what do I mean when I say speculative poetry?”

And the answer I came to, based on all the discussions and my own feelings as a writer, is that in some ways its very simple but also very difficult.

On one hand, you can define it as narrowly as poetry published under the umbrella of spec fic. By this I mean that they’re published in spec fic magazines by authors who call their poems speculative poetry. In some ways, that’s really useful. It sets apart poetry published in literary venues from poetry published in speculative-specific magazines.

But I think that definition is too restrictive.

For me, it comes down to what role is the imaginary playing. It’s about whether the speculative element is more than a metaphor.

In the case of stuff published in genre magazines like Strange Horizons, Uncanny, and Abyss & Apex, it’s pretty straightforward. When we have a poem about a dragon, maybe it’s a metaphor, but also there’s a dragon here. If there wasn’t a dragon in it, we wouldn’t have wanted to publish it at this spec fic venue.

But it also comes down to something you can feel in the text. When they say alien, do they mean space aliens, or just a sense of otherness?

In my experience, I find that you can identify when a speculative poem by it’s feeling. It’s like the Supreme Court case with the famous porn test: ‘I know it when I see it but I can’t define it.’ You can really feel when a speculative element is there on its own terms as well as doing whatever figurative work it’s doing.

And that for me is what makes a poem a speculative poem.

IP: Who are some of your favorite poets?

TB: There are a lot of great poets out there. I’m a big fan of some of the main people we see in the speculative space. R.B. Lemberg, Amal El-Mohtar, Beth Cato, Sonya Taafee.

But I’m also reading lots of other kinds of poetry as well. I tend to gravitate toward poets like Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Lo Kwa Mei-en, and Franny Choi.

Recently I’ve been reading Anne Carson, her work is really special. And Danez Smith, Patricia Smith, and T.S. Elliot.

IP: You’ve had some of your work published in Fantasy Magazine, Liminality, and GlitterShip, and your new poem “Fountain Found in an Abandoned Garden” is out now from Abyss & Apex, right? Can you tell me more about your inspiration for that poem?

TB: That was a really fun and exciting one to work with. It started in several places at once, how many of the pieces we’re excited about as writers start.

One of the places of genesis for the very first draft was written in the advanced poetry workshop in my senior year of undergrad, fall of 2018. The assignment was to write several abecedarian poems, and those are poems where each line begins or ends with one letter of the alphabet. It’s a form I’m really excited about, it’s a major thread in Lo Kwa Mei-en’s The Bees Make Money in the Lion, which is actually the subject of my Master’s thesis.

I tried several poems, A-Z one word per line, Z-A one word per line, and A-Z where I could have as much space as I wanted.

It was the third poem that eventually became “Fountain Found in an Abandoned Garden.”

One of the other strands that goes into this poem is all of my feelings about secluded spaces, statuaries, and garden spaces. I’ve been writing about this idea a lot, and this was my most recent attempt at it.

You go to a place and it’s all alone, you’re all alone. It’s not about being lonely, I wasn’t a lonely child. I had a lot of friends and I loved them, but sometimes I wanted to go to a place and be alone, to feel like the whole world fell away.

In those spaces, I was free to be anyone and anything, not having to worry about the expectations of friendship or growing up in a small town.

There are places like that all over, but that place I’m talking about is at the base of the fire escape at the church by my house where I grew up. There are boring evergreen trees hiding this place, but it’s a tiny slate patio with a bench and flowers in pots, and the fire escape.

That space embodied an absolute freedom, and I’d describe it as a homosexual place, which makes to sense. It’s not a culturally gay space, more of a personally gay space for me. I never knew anyone who ever looked in on this place, as far as I could tell, no one had set foot onto that patio, and that is the space and energy I was tapping into with this poem.

That feeling of twin freedom and aloneness, which is everywhere, but at the same time very hard to access. It’s exciting and hopeful but also kind of sad because it requires acknowledging that the person you are in relation to other people is not, and will never be, all the person you are. The poem isn’t just about the closet, obviously, it’s about lots of other things, but it is also about what it was like when the closet was part of my life, even though it isn’t anymore.

IP: You mentioned that you studied speculative poetry for your Master’s thesis at the University of Chicago; what did you learn about spec poetry there that you hadn’t previously thought about or learned?

In some ways, everything. I really learned so much about how to approach big questions I have about genre in a more principled way. But I also learned to be a better reader, both of poems and criticism. And the really important thing was that I gained a new appreciation for the relationship between the poem as the object, the poem as the project, poetics as the question, and poetics as the theory.

It helped me clarify the ways in which writing a poem is both similar to and different from reading a poem. They were things I had been thinking about and it was largely a confirmation of instincts, but it gave more clarity to those similarities and differences.

And it helped me understand the relationship between questions of ‘how does this text work’—that’s poetics as the questions. And interpretations of how does the poem in general work, what is the poem in general?

How can I use individual poems to learn about poetry at large and vice versa.

It was a big complement to the critical side of my undergrad, which really taught me about how to read criticism and when to realize that criticism is about the author, and that’s most notable in cases like T.S. Elliot.

He’s sort of a pet case for me. I find his critical writings, things like Tradition of Individual Talent, and his Hamlet essay, to not necessarily be right. I don’t think he’s right about the poems or texts he’s writing about.

But it told me a lot about what he wanted to do in his own writing.

If you approach The Wasteland and think ‘what is this fragmented, sprawling monster,’ you can go, wait a second, T.S. Elliot thinks that literature is the invocations of the right words in the right order to produce the correct response.

What does it mean to read The Wasteland as an attempt to elicit a uniform, overwhelming response, almost as if by magic?

And so, at Chicago, I was able to go the other direction, thinking about how do I take poems and from them abstract a theory?

IP: What kind of projects are you currently working on? Can we expect to see a book of poetry from you in the future?

Although I have a chapbook manuscript, about ten poems, that I’ve been shopping around occasionally, I am nowhere near ready to assemble a full-length manuscript.

I’m excitedly awaiting the day I’m ready to embark on that project because I like thinking about poems together in context to each other. But I’m not there yet.

Right now, I’m writing a variety of things. Quite a few religious-of-sorts poems in the works, prayers and spells to a variety of invented gods. One I have no idea what to do with because it’s a doctrinal document. I like the entity I’ve invented, it’s appeared in two poems so far, but I don’t know what to do with the second one.

I’m also doing a series of poems based on “East of the Sun, West of the Moon” which is deeply unfinished, and I’m not totally sure if it will go anywhere.

I have some other unconnected projects too; I sort of fill notebooks at random. A lot has happened in the past twelve months!

Thanks to Tristan for having this delightful conversation! If you liked this interview, check out some of our other author interviews:

Science Fiction Awards Not Everyone Knows

We’ve all heard of the Hugos and the Nebulas. They’re the big names when it comes to science fiction awards.

And while having a Hugo or a Nebula is a great achievement, there are plenty of other reputable awards for science fiction books (and short stories and poetry) out there too.

Here are a few science fiction awards not everyone knows about!

- Gaylactic Spectrum Award

- Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award

- Dwarf Stars Award

- Eugie Award

Gaylactic Spectrum Award

The Gaylactic Spectrum Awards were initially presented by the Gaylactic Network, first established in 1998 and first awarded in 1999. However, they created their own organization in 2002 called the Gaylactic Spectrum Awards Foundation.

The award focuses on works of sci-fi, horror, and fantasy that positively represent the LGBTQ+ community.

Categories

They have award categories for Best Novel, Best Short Fiction, and many others.

Previous Winners

Nicola Griffith won three awards, making her the most awarded novelist in of the GSA. She has also been given five nominations, alongside Melissa Scott, making them both the most nominated writers in this spectrum.

If you’d like to nominate a piece for this science fiction award, please visit their website.

Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award

The Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award was created in 2001 by the Cordwainer Smith Foundation in memory of science fiction author, Cordwainer Smith.

Cordwainer Smith was a pen-name for Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, a former US Army officer and expert in psychological warfare. He wrote a number of science fiction novels, but his career was cut short in 1966, when he suffered a heart attack.

His memorial award focuses on under read science fiction or fantasy to purposely draw more attention to the authors.

Categories

The awards go to Best Underrated Science Fiction and Best Underread Fantasy.

Previous Winners

British writer and philosopher Olaf Stapledon was the first winner of the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Awards, and since 2001, the awards haven’t stopped. Most recently, British writer David Guy Compton (or D. G. Compton) won the last award in 2021.

Other previous winners were:

- R. A Lafferty (2002);

- Edgar Pangborn (2003);

- Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore (2004);

- Leigh Brackett (2005);

- William Hope Hodgson (2006);

- Daniel F. Galouye (2007)

- Stanley G. Weinbaum (2008)

- A. Merritt (2009), Mark Clifton (2010);

- Katherine MacLean (2011);

- Fredric Brown (2012);

- Wyman Guin (2013);

- Mildred Clingerman (2014);

- Clark Ashton Smith (2015);

- Judith Merril (2016);

- Seabury Quinn (2017);

- Frank M. Robinson (2018)

- Carol Emshwiller (2019); and,

- Rick Raphael (2020).

Dwarf Stars Award

The Dwarf Stars Award was established as a counterpoint to the Rhysling Award in 2006, both awards given by the Science Fiction Poetry Association. Dwarf Star was created to honor short form poetry, as many of the winners of the Rhysling award wrote in long forms.

This award focuses on sci-fi, horror, and fantasy poems of ten lines or fewer, published in English in the prior year.

Categories

Categories include Best Science Fiction Author, Best Horror Author, and Best Fantasy Author.

Previous Winners

The awards have first, second and third places. American writer Ruth Berman won first place in 2006, and John C. Mannone won first place in 2020 (the last award given so far).

Other previous first-winners include: Jane Yolen (2007), Greg Beatty (2008), Geoffrey A. Landis (2009), Howard V. Hendrix (2010), Julie Bloss Kelsey (2011), Marge Simon (2012), Deborah P. Kolodji (2013), Mat Joiner (2014), Greg Schwartz (2015), Stacy Balkun (2016), LeRoy Gorman (2017), Kath Abela Wilson (2018), and Sofia Rhei (2019).

Eugie Award

The Eugie Foster Memorial Award (or simply Eugie Award) was first presented in 2016 at Dragon Con’s awards banquet and has been ongoing ever since. It was named in honor of prolific speculative writer and editor Eugie Foster.

This award focuses on short speculative fiction published in the previous year.

Categories

The Eugie Award categories include Best Innovative and Essential Short Speculative Fiction.

Previous Winners

The American writer Catherynne M. Valente won the first award back in 2016, and the Canadian writer Siobhan Carroll won the last award in 2020.

Other previous first-winners include N. K. Jemisin (2017), Fran Wilde (2018), and Simone Heller (2019).

There are plenty more science fiction awards out there, some well-known, some a bit more niche. Is there an award that you follow closely? Comment down below!

And if you’re interested in the Mike Resnick Memorial Award for Short Fiction, you can check out the guidelines here:

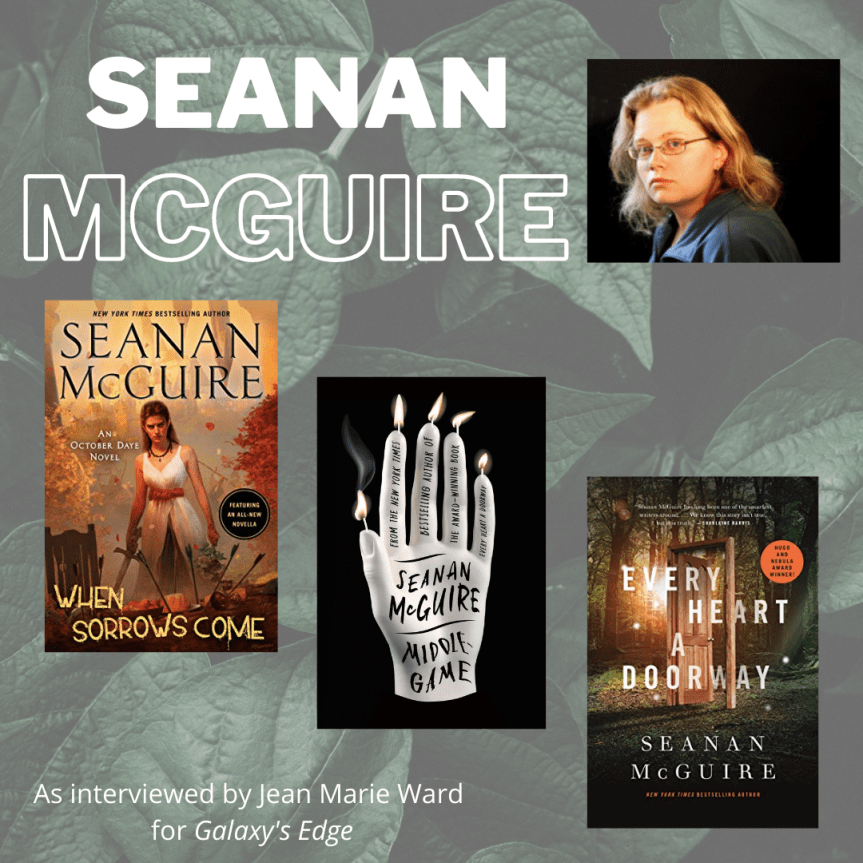

Galaxy’s Edge Interviews Seanan McGuire

In the July 2021 issue of Galaxy’s Edge, Jean Marie Ward interviews Seanan McGuire. They discuss all manner of things, including writing, publishing, feminism, and much more!

Check out the full interview below, and if you like this content, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge, where we bring you the best speculative fiction from writers new and old, as well as thoughtful interviews and book reviews.

About Jean Marie Ward

Jean Marie Ward writes fiction, nonfiction and everything in between. Her first novel, With Nine You get Vanyr (written with the late Teri Smith), finaled in both the science fiction/fantasy and humor categories of the 2008 Indie Awards. She has published stories in Asimov’s and many anthologies and provided an in-depth look into an award-wining artist, with her book Illumina: The Art of J.P. Targete. Her second nonfiction title, Fantasy Art Templates, marries the superb illustrations of artist Rafi Adrian Zulkarnain with pithy descriptions of over one hundred fifty creatures and characters from science fiction, fantasy, folklore and myth. A former assistant producer of the local access cable TV program Mystery Readers Corner, Ms. Ward edited the respected webzine Crescent Blues for eight years, and co-edited Unconventional Fantasy, a six-volume collection of fiction, non-fiction and art celebrating the fortieth anniversary of World Fantasy Con. She has also contributed interviews and articles for diverse publications before starting interviewing for Galaxy’s Edge magazine. Her website is JeanMarieWard.com.

FOLKLORE, PLAGUES, AND ANGLERFISH

What are award-winning, SFF writers made of? In the case of Seanan McGuire—author of the October Daye, InCryptid, Wayward Children series and more under her own name, as well as the science fiction horror novels of her alter ego Mira Grant and the children’s fantasy she writes as A. Deborah Baker—the answer encompasses music, art, anglerfish and 3 a.m. fanfiction attacks. Strange as the recipe may seem, you can’t argue with the results. To date, McGuire’s honors include the 2010 John W. Campbell Award (now the Astounding Award) for Best New Writer, the 2013 Nebula Award for Best Novella, five Hugo Awards, a record-breaking five Hugo nominations in a single year, and five consecutive Hugo nominations for Best Series—to say nothing of the seven Pegasus Awards she’s won for her filking. Eager to learn more, Galaxy’s Edge sat down with the California native a few days before the release of her latest novel, Angel of the Overpass, to talk about her earliest days as a writer, her fascination with microbial marvels, and expanding the notion of personhood on the page.

Galaxy’s Edge: When did you first realize you wanted to become a writer?

Seanan McGuire: When I found out it was an option. I was a very weird child. I was credulous in some ways that sound fake to me now, even though I remember the experience, and disbelieving in other odd ways. It made perfect sense to me that lunch boxes would grow on trees, which happens in The Wizard of Oz. And if there are lunchbox trees, why wouldn’t there be book trees? I had never met an author. I had never met anyone who said they were an author. I just figured that books happened. Being a storyteller felt like too much of a responsibility for any one person. It didn’t make sense, given the breadth of stories I could experience if I went looking, that anyone would do that.

At the time, one of my favorite shows was an anthology series on the USA Network called Ray Bradbury Presents. Every episode began with this white-haired dude sitting at a typewriter pounding away. Then there’d be a ding, and he would pull a sheet of paper out of the typewriter and throw it into the air. It fluttered down and formed part of the logo.

One day I asked my grandmother, “Who the heck is that? Why is this old dude taking up like a whole minute of what could be story?”

She said, “That’s Ray Bradbury. He wrote all these stories.”

That was my bolt of lightning moment. Wait, one person made all this up? This is all fake, and one person sat down and thought of it, and that was okay? That was allowed? I pretty much decided on the spot that that’s what I was going to do.

Galaxy’s Edge: How did you get from there to your first published stories?

Seanan McGuire: A lot of fan fiction. So much fan fiction. Shortly after the Ray Bradbury Presents incident, my mother brought me this gigantic manual typewriter from a yard sale. It cost five dollars, and it disrupted her sleep for years. It weighed more than I did. I would sit down, feed my paper in, and pound away for hours. I was seven. Seven-year-olds don’t sleep like humans They’re people, but they aren’t humans yet. The idea that 3 a.m. is not a good time to start working on a giant manual typewriter that sounds like gunfire does not occur to their tiny seven-year-old brains. And since the typewriter was so big compared to how big I was, I couldn’t just type, I had to assault the keyboard. I hunt and peck at approximately two hundred forty words per minute…

Because I was writing for hours at night, I would write stories about my cats or what I did that weekend or—and this is key—about having adventures with my friends, the My Little Ponies in Dream Valley. I had no idea that a self-insert was a bad thing. I was seven. I had no idea that saying I would be good at everything the ponies needed me to be good at was being a Mary Sue. Again, I was seven. I did this for years.

The thing about writing is the more you do it, the better you’ll get. You can get good at some really bad habits. But putting words in a line, forming sentences, building sentences into a paragraph, building enough paragraphs onto a page to have a page? That’s a muscle. That’s something that you learn by doing. I turned out reams and reams and reams of not goodness, but it taught me how to put together a page.

Then I got to high school and discovered real fanfic, where you write in a universe. [Fanfic] had these weird unspoken rules, like the Mary Sue Litmus Test, and what was and was not appropriate to do. One of the first pieces of advice I was given was never write a character who looks like you, even if they’re canonical, because everyone will assume that the blonde girl writing about Veronica Mars or Emma Frost is really writing about herself, and that’s not okay. At some point, every dude I know writes about himself having magical adventures in a magical D&D land and getting all the hot elf babes. But if a blonde woman writes a blonde character or a Black woman writes a Black character or anything superficially similar to their appearance, it doesn’t matter how integral that character is to the story, it’s proof they’re sticking themselves in the story, and that’s bad. I disagree with this, in case you can’t tell.

Galaxy’s Edge: What about the little blonde girl in the InCryptid series?

Seanan McGuire: I ultimately got around the problem by making everything fanfic. Verity is basically Chelsie Hightower from So You Think You Can Dance. The InCryptid series was a response to my PA saying, “Please, write something that gets us invited to go backstage on So You Think You Can Dance.”

But in the beginning I just wrote a lot of fanfic. The more fanfic I wrote, the better I got at things like plot and structure and actually writing a 20,000-word, a 50,000-word, a 100,000-word story that wouldn’t bore my readers. Eventually I started writing original fiction, which pretty much went nowhere. I would write it, I would be happy with it, and then I would revise it, because when no one’s publishing you, masturbatory revision takes 90 percent of your time.

One day, my friend Tara, who knew me from the fanfic community, said an agent friend of hers was branching out and starting her own boutique agency. And because [the agent] was from the fanfic community, she was looking for fanfic authors with an interest in their own original fiction. I sent her a copy of Rosemary and Rue. She sent me back a list of suggested revisions. I did one more revision, and she signed me. Then everything went nuts.

Galaxy’s Edge: Because you had something else in the pipe—something that became the Newsflesh series.

Seanan McGuire: The thing about writing very fast is I write very fast. When we took Rosemary and Rue to DAW, I had already finished [the] first three books in the October Daye series (Rosemary and Rue, A Local Habitation and An Artificial Night). I also had a rough and not-so-great draft of Book Four, Late Eclipses, but I had time to revise and beat it into a shape. I also had Feed, my biotechnical science-fiction thriller. We took Feed to Orbit.

With DAW, we were very fortunate in that a good friend of mine was also a DAW author and able to give me the nepotism referral to her editor. She wasn’t inappropriate about it. She just said, “This is my friend, Seanan. She wrote a really good book. I think you’ll like it. Let me introduce you.”

At Orbit, we went through a more normal submissions process. We wound up with DongWon Song, who’s now an agent but at the time was an Orbit editor. They were the perfect editor for that series. I miss working with them.

Galaxy’s Edge: You mentioned in another interview that you took the “dragon major” in college: a double major in folklore and herpetology. How did that play into your writing and your day job?

Seanan McGuire: I’ve never had a day job that used either parts of my degree. I think that anything we do or are interested in will play into our writing. We can’t help it. It’s part of why I get kind of angry on a personal level at authors who say that fanfic is bad and you can’t do fanfic ever. Well, okay, I’m gonna go over your work and find every element that you took from Shakespeare. How dare you write fanfic? I’m gonna find every element you took from Austen or from Poe. Or from fairy tales, from the Brothers Grimm, from Disney.

Humans are magpies. We do not thrive on original thought. That’s not how we’re constructed. If you have one truly original thought in your entire lifetime, you’re about average. You’re doing well. We want to think of ourselves as these incredible original innovators of everything, but that’s not how monomyths work. It’s not how human psychology works. Everything’s a remix.

Because I studied both the so-called soft science of folklore and the hard science of herpetology, I have, to a certain degree, the flexibility of thought arising from two very different disciplines. It doesn’t make me better or worse than anyone else. It just means that I have been trained to look at things from those multiple angles. There are still ways of thought that are completely alien to me. I have no experience or background in any kind of physical handiwork. I don’t know how to fix a car. If you hand me a hammer and a nail, the odds are good that what I’ll hand you back is a trip to the ER, because I have just broken my hand. There are patterns and ways of thought that I can’t wrap my head around. But having that initial flexibility made it easier for me to switch gears as I got older.

You can see the dichotomy in the two sides of my work. When I write as Seanan, I tend to write very monomythical, very inspired by folklore, very poetic. One of my favorite copy editors says, when you copy edit my work for flow and for tone, you need to remain aware of the fact that I have never written a book in my life. What I write is 300-page poems. That’s not inaccurate. The way I build sentences, the way I phrase things and manage the rising action very much reflects the fact I was a folklore major who studied oral histories for a long time. Within a single book, there will usually be one or two phrases that I hit very often. It’s not because don’t I think my readers are clever; it’s how I assemble a narrative.

When I write as Mira Grant, [the stories] are very biological. I started out wanting her to be a horror author. It turns out she’s not, because I am so much less interested in the screaming than I am in the scalpel. I want my science to make sense, and I want my biology to make sense. That’s what makes me happy.

Galaxy’s Edge: Even when dealing with mermaids?

Seanan McGuire: Even when dealing with mermaids. The mermaids [of Into the Drowning Deep] were actually a direct attack on DongWon. When they were my editor, I would threaten to write them a book about anglerfish mermaids.

The way anglerfish reproduce is the male anglerfish will be attracted by the smell of the female anglerfish’s pheromones. He thinks she’s so sexy that, when he finally finds her, all he wants to do is eat her. So, he chomps onto her skin. This causes a chemical reaction which melts his skin and fuses him with the female. Her body will gradually absorb his until all that’s left is his scrotum.

The female now has a pair of testicles sticking out of her, and she can control when sperm is released. One female anglerfish can have hundreds of sets of testes stuck to her from men that she has effectively eaten. In terms of size, the male anglerfish is about one and a half to two inches long. The female anglerfish is the size of an alligator snapping turtle. It’s one of the biggest cases of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate world…. The biology of my mermaids was preset by that horror.

Galaxy’s Edge: You didn’t work in herpetology, but I understand your former day job used a lot of your science background, which contributed to Feed and your all-too-plausible zombie apocalypse.

Seanan McGuire: Yep. I am a prophetic genius. The entirety of COVID-19 has been an exciting game of people telling me: “You were right about everything two years ago.” Yes, I was. Thank you. There you go.

Galaxy’s Edge: Are there more such prophecies in our future? Should we be shivering in our boots?

Seanan McGuire: Right now, I am not doing anything super pathological, in part because I lost a lot of optimism in the current pandemic.

People ask me all the time, “What do you feel like you got wrong? What would you do differently?” The answer is I had too much hope. Part of that is Feed was written and published before the real rise of Facebook, before the rise of microblogging, [at a time] when if you wanted a blog, you still had to set up a blog and usually wrote longer-form things. Readers could get an idea of who you were, your likes, your dislikes, your prejudices. You weren’t just delivering speedy sound bites of hatred and vitriol.

I like the flexibility and speed of Facebook and Twitter in terms of things like coordinating disaster response. But what we’ve seen is we’re not doing as much as we could, because we’ve all learned to hate each other in this time of super-fast microblogging, botnets and trolls.

There was a point, early in the current situation, where I posted a thread on Twitter (which is my primary habitat most of the time) about ways to protect yourself from con crud and the seasonal flu. There is a tweet in that thread which can be seen as equating coronavirus with airborne diseases.

At the time, the official position was that the disease we’re dealing with now was not in fact airborne, even though anyone who had ever worked with any coronavirus anywhere was saying, “No, it’s probably airborne. If you don’t think it’s airborne, you’re probably wrong.” The science said, “Probably airborne,” but the official public information said, “Not.”

So, I posted this tweet. It’s in the middle of a relatively innocuous thread. Hey, wash your hands, drink lots of water, sleep. I know that you don’t feel like those last two have anything to do with your health at a convention, but they genuinely do. The more well hydrated you are, the less likely you are to pick up most common crud. That sort of thing. For three days I got barraged by trolls screaming at me for being so irresponsible as to imply that this could be an airborne disease. They weren’t real people. None of them had existed on Twitter prior to a month previous. They weren’t there to engage in conversation. They were there to yell at me. That’s because it’s so easy to set up a word finder, something that triggers off a keyword and unleashes this tide of hating on people who say things you don’t like.

My pandemic response [in Feed] was founded on the idea that the news would lie to us (which we saw will happen), and that in the absence of the news, citizen scientists and citizen reporters would rise as a source of credible information. Instead, what we saw is people will rise to sell you miracle cures made from mercury and tell you that your children have COVID because they were given a vaccination twenty years ago, even though your children are eleven. It’s just bad.

I am not currently working on any diseases because part of what I enjoy about writing pandemic fiction, why it makes me happy to be Mira Grant, is that diseases fascinate me. I find them really interesting—the mechanisms by which they work, the things that we know they can do to us, the things that we’re still finding out they can do to us. They’re amazing. They’re so simple. They’re not living things. They’re basically malware. They’re just these little instruction bundles that plug into your body and go haywire.

It is easier for me not to be afraid of them if I understand them and am writing about them and having a good time. It feels a little mean to have a good time with diseases right now. The way I have always coped with the horrible diseases I created was by going, “No-no. Once enough people started dying, we would care. Once enough people were at risk, we would care.” But what I’ve seen is that far too many of the people in positions of power wouldn’t.

Galaxy’s Edge: There are those who say, if this world fails us, we should write the world we want to live in. What would that world look like for you?

Seanan McGuire: The way I would like the world to be is incredibly overly optimistic. I don’t think we’re going to get there in my lifetime. We have enough food that no one needs to be hungry. We have enough resources that no one needs to be homeless, no one needs to be sick. We have enough of everything that no one actually needs to feel like they don’t have enough. But there is a point at which anything stops being the thing itself and becomes counting coup. There are people with so much money, they could be spending money every minute of every single day of their lives and not come even remotely close to running out of money. And what do they do? Do they rent Disney World for a month? No. Do they set up a zoo full of tigers in their basement? No. They make more money because they have seen how much they are willing to exploit the world, and they want to make sure there’s no one in a position to exploit them.

I want a world where rich people pay their fair share, where everybody gets safe housing, food, clean water, medical care. Where the color of your skin is not treated as any kind of judgment on your personal character. Where the fact that people love who they’re gonna love is not treated as some kind of judgment on their character. It’s so idealistic. Every step forward is amazing, but we have the potential, as a species, to be so much better. Sometimes we aren’t because it would be inconvenient to be better right now. Sometimes it’s because we don’t want to, or it would be hard or “How can I feel like I am better than you if you have as much as me?”

Galaxy’s Edge: As opposed to seeing equality as a valid goal.

Seanan McGuire: We’ve been unequal for so incredibly long that equality really does feel like oppression to a lot of people who have been on the top of the inequality pyramid.

Galaxy’s Edge: Your fiction celebrates diversity and inclusivity. Is this your way of making the world you write shinier, or is it something that just happens?

Seanan McGuire: A little bit of both. But mostly it’s that anything that is 100 percent straight, white, and able-bodied is unrealistic unless you want to set up a bunch of oppressive structures I have no interest in writing.

The world is not a monoculture. Humanity has never been a monoculture. [A lot of stories] treat humanity like a monoculture where any setting you want to use is just pretty stage-dressing and any character you want to design needs a reason to be something other than what we jokingly refer to as the “Six-fecta”: straight, white, vaguely Christian (but not too Christian; you can’t be too religious) able-bodied, cisgender and male. So many books in our genre still hit all six of those attributes with every main character. The only exceptions are some secondary characters who are women because, otherwise, how do we reward the men for being awesome?

But that’s not the world I live in. I have been a queer, disabled, half-Roma woman for my entire life. I knew I liked girls from the time I was eight. Not in a sexual way but in a “If I’m gonna hold hands with somebody and kiss them” way, I would prefer it be a girl. So I can absolutely say that I was queer when I was eight. I’ve been half Roma since my daddy knocked up my mom in the back of a van, and I’ve been female since I popped out. I’ve done the gender interrogation you’re supposed to do as a cis ally and determined that “girl” is pretty much the label that works for me.

I never had a shot at that Six-fecta if I wanted it. Why would I, as someone who deviates from that “norm” on multiple levels, want to write that norm? I know people who fit it, I love people who fit it. I am not saying there’s anything wrong with them wanting to see characters who look like them. But sometimes I want to see a character who looks like me, and that means a character with multiple overlapping identities all of which inform her daily life.

Sometimes, people I know will tell me they want to see a character that looks like them, and they don’t get to do that very often. Then I will make a genuine effort to include a character that looks like them, because I want them to have that experience. We learn how to human from stories. Like I said before, humans are not built for constant original thought. We learn what a person looks like from the stories people tell us. Sometimes that is learning: “Wait, that’s me. I’m a person.” And sometimes it’s learning: “Wait, that’s Jean Marie. Maybe she’s a person too.”

Culturally, we have done ourselves a huge disservice by telling so many stories for such a long time where the only people who got to be at the center of the story were the ones who fit those six attributes, because only those people get fully acknowledged as people by the monomyth we’re living in. That’s not fair and not okay. The only time I tend to manipulate the diversity in a story is if I realize I need to kill somebody. If a group has little representation, you can kill a much larger percentage of that group by killing one character. If I kill a straight white man in science fiction, I have killed one of ninety million straight white men. If I kill a trans woman in science fiction, I’ve killed one of maybe twelve. That’s a very different statement, whether or not I intend to be making it.

So, if someone is in the line of fire and I cannot move them, I will stop, look at what I’m doing, and ask myself: How big a deal is this character to the group they represent? How big a deal would it be if I were reading this book and that character looked like me? Would I have seen me before? That’s not tokenism. I don’t give plot armor to these characters. They can still die. It’s a matter of am I taking away someone’s emotional support character?

Galaxy’s Edge: You have explored just about every subgenre in speculative fiction. Is there any particular kind of story or genre that you would really like to write but haven’t had the chance?

Seanan McGuire: I have an intense, bordering on the ridiculous, fondness for mid-Nineties chick lit, the sub-genre where The Princess Diaries, The Boy Next Door, and Bridget Jones’s Diary live. I’m waiting for the nostalgia wave to whip those back around. I’ve written several. I’m pretty good at it, but there’s no market for them right now. So they sit and occasionally get revised, when I have time, to make sure that they stay up to my current standards. And they go nowhere.

I would also very much like to write a series of cozy mysteries—The Dog Barks at Midnight sort of thing. I have a concept for a fun series of cozy mysteries. But unfortunately, I am told by both my agent and several authors I know who write cozy mysteries, there is no money there. There’s just none.

It’s not that I only write to chase the money, because no one becomes a writer to chase the money. That is the worst decision you could possibly make. Don’t do that, children. Or adults. Or unspeakable cosmic entities. Don’t become a writer because you want to get paid. You will not get paid. But there is a difference between writing something I am truly passionate about, cannot stop myself from writing, that I already know I’m good at, and not getting paid; and writing books in a genre I find charming but not completely compelling, kind-of-wanna-try-my-hand-at but will not get paid. One is a reasonable self-limiting decision. The other is just not bright.

I’d also like to write a truly horrific horror novel that has no science fiction elements. Just horror. I wanna do horror for the sake of horror. I wanna get my Clive Barker on. I wanna get my Kathe Koja on. I can’t. Every time I try, I get distracted by the possibility of science.

Galaxy’s Edge: That’s tragic. Science is death to horror.

Seanan McGuire: Yeah, I love horror so much, and I’m so bad at it.

Galaxy’s Edge: Any closing thoughts?

Seanan McGuire: We are recording this on April 29, 2021. I have a book coming out on May 4 called Angel of the Overpass. It’s the third book in my Ghost Roads series, which is InCryptid-adjacent, published by DAW Books. I won’t say it’s the last, but it is likely to be the final entry in Rose Marshall’s story for a while. So I’m very excited about that.

Over on my Twitter, I just finished a complete review of the October Daye books, because they are nominated for a Best Series Hugo this year. Having grown up in fandom, I tend to be very careful and a little aloof when talking about the Hugos. I remember being told by my foster mother when I was a teenager that it’s gauche to say you want to win. But I really want to win this year.

I feel that the Best Series category was created for urban fantasy. I know it wasn’t created just for urban fantasy, but urban fantasy plays best at series length. It is a story that needs that room to grow and breathe and really be considered as a whole, not just as the sum of its parts. I would desperately like for the first true urban fantasy—just urban fantasy, not urban science fiction, not urban horror, but urban fantasy—Hugo to go to a female or female-identifying author. It’s the only science fiction subgenre that is female-dominated and doesn’t have the word “romance” somewhere in the description. Romance is great. I love romance. I write romance. But female authors get shoved into romance so quickly, whether or not that’s what we want to be doing. Having a subgenre we currently control has always been very very important to me. It feels like a thing we have accomplished as ladies.

So, I would like the first Hugo Award given to a work of pure urban fantasy to be given to a female-identifying author. It doesn’t have to be me. You have many other choices. We are a big and diverse field. But if you’re looking at this year’s ballot, it does have to be me.

Galaxy’s Edge: We’ll keep our fingers crossed and hope the best.

Seanan McGuire: Thank you.

Like our interviews? Read our conversation with qntm, author of There Is No Antimemetics Division!

Sci-Fi Subgenres: Breaking Down the Punks

The practice of segmenting films, books, games, and stories into genres can get pretty tricky. Sometimes, a novel or film fits neatly into the conventions set down by a genre, other times the waters are a little muddier. But sci-fi subgenres have exploded in the past few years, and there a lot more categories with which to classify new (and old) work.

One of the large subsections of science fiction literature classification falls on the ‘punk’. The idea of ‘punk’ literature focuses on the outcasts from society, the rebels, the vigilantes, those who go against the grain. The punks.

Genres like cyberpunk and steampunk sparked a flurry of smaller subsections that have distinct conventions, and often subvert the aesthetics of their parent genre.

In this blog post, we’ll break down some of the well-established ‘punk’ sci-fi subgenres and take a look at the rising stars.

Cyberpunk: Where It All Began

The term cyberpunk is now kind of a commonplace, kitchen-table word. It refers to science fiction literature (and by literature, I lump the written, visual, and interactive together) that takes place in a futuristic world filled with advanced tech, but riddled with socio-economic issues.

Characters in cyberpunk literature are often downtrodden, working-class loners rebelling against some kind of convention, whether that’s their corporate overlords or street gangs that control their neighborhood.

The term cyberpunk came from a short story of the same name by author Bruce Bethke in 1983, even though sci-fi writers had been exploring the themes of the genre years before there was a name to associate with them.

Authors like Roger Zelazny, Philip K. Dick, Gardner Dozois, and William Gibson pioneered the movement with their fiction and non-fiction alike.

Neuromancer (1984) by William Gibson is one of the pinnacles of the cyperpunk genre, and helped bring more attention to the aesthetics of the genre as a whole. Films like Blade Runner, comics like Judge Dredd, and anthologies like Mirrorshades kept cyberpunk in the limelight.

Recently, the genre has gained some attention from the release of CD Projekt Red’s triple-A video game, Cyperpunk 2077. While the game and its release were largely a disaster, it succeeded in introducing newcomers to the genre of cyberpunk.

And with all the attention the cyperpunk genre has received, writers began to deviate from the aesthetics of cyberpunk, sparking new genres like solarpunk and biopunk.

Biopunk Aesthetics

Biopunk as a genre is closely related to cyberpunk. Both are set in dystopian futures with rampant technological advancement.

However, the distinction between the two genres comes down to body modification. In cyberpunk, people often alter their bodies with cyberware and technological implants. Eye implants, enhanced limbs, etc. etc.

But biopunk takes that convention a step further, altering bodies using biotechnology like genetic engineering.

Biopunk still keeps the dark, grungy aesthetics of cyperpunk, dystopian futures; it just focuses more on the implications of governments or corporations using bioengineering as a tool to control people.

Popular books in this genre include:

- The Leviathan Trilogy by Scott Westerfield

- The Xenogenesis Trilogy by Octavia Butler

- Change Agent by Daniel Suarez

Solarpunk Aesthetics

Solarpunk is one of the relatively new sci-fi subgenres, really only established with a set of conventions and aesthetics in the late 2000s. Internet communities and literary icons alike were instrumental in bringing solarpunk into the public eye.

Where cyberpunk is rooted in dystopia and worlds wrought with misfortune, apocalyptic landscapes, and ever-encroaching environmental failure, solarpunk focuses on futures where we’ve overcome issues like climate change with sustainable practices and renewable energy. Hence the solar in solarpunk, in reference to solar energy.

Solarpunk literature often takes an upbeat tone, optimistic about the future and proud of overcoming the issues of the past. Works often have a heavy focus on nature as well as sustainable technology, which is what really sets the genre apart from cyberpunk, a genre that for the most part ignores nature.

Some notable solarpunk works include:

- Walkaway by Cory Doctorow

- Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation edited by Phoebe Wagner and Brontë Christopher Wieland

- Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach

Modern Steampunk and Victorian Steampunk

When I hear the word steampunk, I think of elaborate Victorian-era costumes with neat techy-bits, airships, and tall, whimsical buildings.

The steampunk genre is often described as the point of deviation in our historical timeline where steam power overtakes other forms of power, like electricity. Writers in the steampunk genre explore historical events and settings with the “what if steam powered technology was the end-all-be-all” question in mind. Alternate history narratives, cosplay, and visual art mediums are also very popular in the steampunk genres.

The term steampunk was coined by K.W. Jeter in the 1980s, but the term applied to work published before then, as far back as Jules Verne and Mary Shelley. Steampunk literature generally takes on a more optimistic tone than cyberpunk and dieselpunk (a steampunk derivative).

Settings for steampunk stories are a bit more fluid than cyberpunk’s megapolis dystopias. Steampunk can be set in alternate histories of the Victorian era, in the American Wild West, or even in post-apocalyptic settings.

Popular early voices in the genre, while they might not have considered themselves voices for the genre, include:

- Michael Moorcock

- Harry Harrison

- Paul Di Filippo

Dieselpunk Aesthetics

Just like solarpunk contrasts with cyberpunk, dieselpunk contrasts with steampunk.

Where steampunk draws heavy inspiration from Victorian-era technology and fashion, dieselpunk is rooted in the period between WWI and WWII. Dieselpunk, as the term implies, idolizes diesel-powered machines, and takes on a grungy, darker outlook on the future.

But, just like steampunk, dieselpunk is filled with alternative histories, many of which build off the question “what if the Nazis won WWII?”.

Many of dieselpunk’s seminal works were published before the term was coined in 2001, including:

- The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick

- SS-GB by Len Deighton

- Fatherland by Robert Harris

There Are a Lot More Punks to Speak of…

Exploring these sci-fi subgenres has merely scratched the surface of all the spin-off genres present in sci-fi literature.

Coalpunk and atompunk are derivatives of dieselpunk, lunarpunk is the polar opposite of solarpunk, etc. etc.

If there’s a certain genre you’re interested in learning more about, drop a comment and we’ll explore it in a future post!

5 Popular Sci-Fi Books from the Asian Diaspora

Science fiction has long been criticized for its lack of non-white, non-male writers, and that might have been the case in the early days of sci-fi literature. But in the 21st century, a large number of the most popular sci-fi books were written by the same denomination that were excluded from the genre.

In recent years, many exceptional hard science fiction, cyperpunk, and dystopian novels have come from the Asian and Asian-American diaspora.

Authors like Cixin Liu, Xia Jia, and Ken Liu have made waves in the genre—and beyond—with their fiction, and they’re not alone.

So, without further ado, here are five popular sci-fi books from Asian and Asian-American authors.

The Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu

The Three-Body Problem is perhaps one of the most famous Chinese science fiction novels. The novel won a Galaxy and a Hugo award, and has been the subject of much praise. In fact, Barack Obama plugged it, saying the book was “just wildly imaginative, really interesting.”

The novel is the first book in the Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy, first published as a novel in 2008. Ken Liu, a notable science fiction writer and translator, brought The Three-Body Problem to English readers in 2014.

The Three-Body Problem jumps back and forth between three, interconnected plot lines. But what ties the plot lines together is Cixin Liu’s understanding, and explanation, of complex scientific concepts, everything from astronomy to physics. The language is vibrant and visceral, and Ken Liu’s translation comes with footnotes to help readers understand the Chinese colloquialisms and references, which makes the novel all the more intriguing.

If you love reading marriages of science and class politics, this book is right up your alley.

Ninefox Gambit by Yoon Ha Lee

Ninefox Gambit is intense, complex, and an absolute page-turner. As Yoon Ha Lee’s debut novel, it showcases his linguistic skill as well as his keen sense of plot.

Ninefox Gambit is the first of the Machineries of Empire series, and it won the Locus Award for Best First Novel in 2017.

The story focuses on a young military captain and the spirit of a 400-year-old general as they are thrust into the thick of an intergalactic war.

For readers inexperienced with Yoon Ha Lee’s distinct sense of style, this novel might come off as a bit jarring at first. The visceral descriptions, complex worldbuilding, and throw-you-right-in-the-middle-of-it beginning can make the novel feel inaccessible.

If this is the case, take a look at some of Yoon Ha Lee’s shorter works first. I suggest “Knight of Chains, Deuce of Stars,” and “The Starship and the Temple Cat.”

After you read some of his short stories, come back to Ninefox Gambit. It’s certainly a top-rated science fiction book, for new and old sci-fi enthusiasts alike.

Waste Tide by Chen Qiufan

Originally published in 2013, Waste Tide was Chen Quifan’s debut novel. The book was translated into English by Ken Liu in 2019 and received rave reviews from Western audiences.

Waste Tide tackles issues of human waste, particularly e-waste, as well as class-politics in a dystopian future. The setting of the novel, the Silicon Isle, was based on Chen Quifan’s childhood home in the Shantou prefecture, China.

The Shantou prefecture has achieved notoriety as one of the world’s largest e-waste dumping sites, where a few businessmen made fortunes on the labor and misfortune of local waste-sorters. This too makes it into Waste Tide; when a sentient WWII virus incites a class-war, pitting the locals and waste-workers against the wealthy families reaping the benefit of others’ misery.

If you’re a fan of novels with environmental themes, vast scrap-heap vistas, and fights against social injustice, Waste Tide hands you all three and then some.

Vagabonds by Hao Jingfang

Vagabonds was originally published in 2016, and was then translated by Ken Liu and released to Western audiences in 2020. It is Hao Jingfang’s first novel, and it was met with high praise.

Hao Jingfang also landed a Hugo Award for her novelette, Folding Beijing, becoming the first Chinese woman to ever win a Hugo!

Science fiction is ripe with interplanetary and interspecies diplomacy, but Hao Jingfang takes that idea to the next level. Set 200 years in the future, the citizens of Earth and Mars are at odds and a team of young ambassadors must bridge the gap between their birth planet and humanity’s ancestral home.

Hao Jingfang has a background in both physics and economics, which she employs to expert degree in Vagabonds. If you’re a fan of James S.A. Corey’s Expanse series, Vagabonds is a book you have to read.

Clone (Generation 14) by Priya Sarrukai Chabria

This book is a bit different from the others we’ve discussed. While this Clone hasn’t won awards and gained worldwide recognition, it’s still a striking piece, and a worthy addition to this list.

Priya Sarrukai Chabria, a well-known Indian poet, weaves together the science fiction genre and the aesthetics of classic Indian poetry. The result is a haunting dystopian world of governmental control and quiet resistance.

If you’re looking for a different take on the cyperpunk/dystopian genre, Clone fits the bill. Priya Sarrukai Chabria’s unique voice and keen understanding of psychology makes for an engaging read.

NOTE: In 2008, Zubaan Books published Priya Sarrukai Chabria’s novel Generation 14, which was then reprinted under the title Clone in 2019. If you’re looking to buy this book, get the Clone edition. The first edition is quite expensive and hard to find.