It’s back-to-school time again, colder weather is coming, and the kids will soon be spending more time inside.

So, we dug around (consulted my best friend and a professional YA librarian), and asked for some recommends for our young adult readers.

Check out the hot new SF titles below and see if one of these books will lure the kids from their gaming consoles and set them off on an adventure to outer space!

Category: Sci Fi Subgenres

Autumn Reads: 5 New Sci Fi Books in 2022

It’s that time of year, Labor Day is just around the corner signaling the end of summer, the kiddos are headed back to school, and we’re all going to have some extra afternoons free just for reading—right? *wink*

Continue reading “Autumn Reads: 5 New Sci Fi Books in 2022”What is Lunarpunk, And Can It Fix Solarpunk’s Problems?

So, I have to be honest, I’ve been doing a lot of research into what makes particular sci fi subgenres tick. After writing about the solarpunk genre a few weeks ago, something didn’t sit right with me.

After doing some more reading, I’ve pinpointed a few issues with the idea of solarpunk, at least, with how it’s been previously defined.

This goes back to the idea of the punk—the social deviant and system-breaker—and how that really applies to these genres. In the “good-place” utopia that solarpunk strives to be, where does the punk come into play?

And what is lunarpunk? The dichotomous relationship with solarpunk really sets up a whole new perspective that opens up how we can look at the genres.

Problems With Solarpunk

One of the primary things I find a bit troubling about solarpunk as an ideology is the insertion of the ‘punk’. Now, previously, I had defined the solarpunk as being someone who “cares a lot less about rebelling against a system that impacts them as an individual, but instead takes a more environmental approach. They are eco-activists who aim to right the wrongs of the past with technology that is sustainable and renewable.”

On the surface level, I think this is still true. It’s an easy way to define the general mindset of the solarpunk in fiction, and in reality.

However, I overlooked the fact that solarpunk is so dedicated to the creation of a unified collective, that the ‘punk’ might end up slipping out of this collective. You simply can’t have a collective of punks, because that’s counterintuitive on two fronts. So where does the punk fit in a utopia they helped to create? Does the cycle continue after the ideal world has been achieved? What point is there in a rebellion when all is seemingly good?

To rectify this little oversight, we don’t have to completely rework the philosophy of the genre, we simply have to break it up.

We can look at it in three stages:

Three Stages of Solarpunk

Pre-solarpunk is (hopefully) the current state of the world today, in 2022. The climate crisis is getting worse by the day, biodiversity is rapidly deteriorating. But, the fundamentals of change are happening. You’re reading this blog, people are writing eco-fiction and using their skills to work toward a sustainable future.

Solarpunk really picks up when change is acted upon in radical ways. When rebellions begin and oppressive systems are picked apart. This stage is revolution, where the punks take their stand and worldwide change comes to fruition.

Post-solarpunk is really where a lot of the literature defined as “solarpunk” fits in. This stage is when the revolution has been completed, and the systems in place are all working together toward the “good-place” utopia. There will still be problems, sure, but the radical nature of the punk as defined by the revolution stage is no longer condoned. The system in post-solarpunk gets as close to the perfect, sustainable world as possible.

In the post-solarpunk world, I might venture so far as to define the punks as philosophical solar-anarchists. These people aren’t radicalized to the point of revolution (because their revolution has already occurred) but they still operate on the fringes, working against systems they deem as oppressive, or ones that might become oppressive. Traditional philosophical anarchists defy social order and state control, with the ultimate goal of freeing the individual from oppressive systems.

We might think of the post-solarpunks as being the watchers on high of the new society. The systems that replaced the capitalist regime are still a step away from true self-governance, but the post-solarpunks tolerate the new system.

Where Does Lunarpunk Come In?

Lunarpunk is the other side of the solarpunk coin. It’s a very new genre, and it’s more rooted in aesthetics and spiritualism than solarpunk is. While you might be able to skew solarpunk as a political ideology, lunarpunk is much harder to pin down.

No one person has been accredited with the creation of lunarpunk, but there are quite a few people on the Internet that have contributed to the philosophy of the genre.

In an expansive Tumblr comment from thecarboncoast, lunarpunk is defined loosely as:

“Aspeculative fiction style/genre defined by an obscured, shrouded, and/or dark near-future where the business of its inhabitants is done in secretive, cryptic or mysterious ways, accentuated by a visual style hearkening to lunar, occult, Pagan, Wiccan, Satanic, Anarchaic, Chaotic, practices, and comprised of world-building details which are more ideal for introverted, quiet, isolated or self-reliant people. Doesn’t mean an extroverted Christian isn’t part of Lunarpunk, or that someone who practices anything mentioned above isn’t part of Solarpunk. But in terms of what defines Lunarpunk as a genre, you would be more likely to see small sects of persons worshiping (or devoting to) The Self rather than The Other.”

So, it’s clear the lunarpunk operates side-by-side with solarpunk, with a duality that’s often characterized by the yin and yang symbol. The presence of spirituality as a defining feature is really what seperates lunarpunk from solarpunk.

Where solarpunk is a calculating genre that places a focus on the breakdown of societal structures—politics, religion, media, etc.—lunarpunk embraces the loose structure of spirituality and champions individuality.

Instead of a focus on the technology and practices for advancing society, lunarpunk is more about creating a more sustainable sense of self.

One way I’ve seen this concept described is that the sun represents the consciousness, while the moon represents the subconsciousness. It makes sense, primarily because lunarpunk revels in the unexplainable, while solarpunk focuses on reality.

Can There Be a Solarpunk Without Lunarpunk?

Part of the reason I was troubled by solarpunk was because there seemed to be a loss of the individual. Sure, individuals are the ones behind great ideas for sustainable technology, and a more accepting society allows people to be who they want to be.

But the individual is always talked about in connection to society, and that, even in a punk sense, isn’t what individual means.

After learning about lunarpunk, I realized that the two genres must coexist together, lest they both evaporate. Lunarpunk accounts for the individual outside of the societal sphere. Spirituality is largely an individual journey, and lunarpunk’s secretive, mysterious nature supports the development of individual politics and spirituality.

In this regard, I think that the “punk” in lunarpunk is about breaking away from society, no matter how green and pure and optimistic it may be. The dichotomy of solarpunk/lunarpunk levels both of the genres out. There’s a balance that’s necessary for survival. Focus on solarpunk for too long, you lose sight of who you are for the greater good of the society, and if you focus on lunarpunk for too long, you become isolated and disconnected from others.

And to answer the titular question: yes, I think lunarpunk succeeds in solving some of solarpunk’s problems. Not all of them, but those are bound to work themselves out as the two genres converge and grow together.

How Solarpunk Strives To Rectify Our Future

Every day there’s a new environmental disaster on the news, or a new forecast for when climate change will reach critical mass. All of the impending doom features can leave you feeling down and out, hopeless in a stark grey world.

But not everything has to be so grim. Solarpunk, a relatively new branch of science fiction, aims to bring some light to the otherwise dark future. Solarpunk technology and ideologies paint a picture of sustainability and equality, a future where art, science, and nature coexist in the same spaces.

What Is Solarpunk?

We talked about solarpunk a bit in a different blog post where we discussed the punk sci fi subgenres, but we’ll elaborate a bit more here.

Where genres like cyberpunk are characterized by an overarching pessimism about our futures, solarpunk seeks to instill some hope into those visions of the future. Cyberpunk is about how technology impacts the human existence, with a focus on hardware modifications. And biopunk is all about how biology can improve the human condition, with a focus on genetic editing.

In both of those genres, the idea of the ‘punk’ is someone who is culturally or ideologically deviant from a perceived norm. Where ‘punks’ as we know them today are stereotyped as people who skateboard, die their hair, and pierce their nose, the punk of the cyberpunk/biopunk world takes body modification to the next level.

This kind of punk breaks the conventional norms of the body. The solarpunk cares a lot less about rebelling against a system that impacts them as an individual, but instead takes a more environmental approach. They are eco-activists who aim to right the wrongs of the past with technology that is sustainable and renewable.

Solarpunk, perhaps more than any other genre, can act as a political mindset. Because of the environmental focus, it almost inherently comes off as an anti-capitalist—sometimes anarchist—genre.

In essence, solarpunk as a genre is a realistic, hopeful glimpse into a future that’s powered by sustainable practices and inclusivity.

The Solarpunk Mission: Reach Eutopia

So, we know that solarpunks want to improve our futures by using technology that’s available to them, but are also eco-conscious and deviant from the societal norms. This means that we can see a lot of off-the-wall, genius ideas coming from people who ascribe to the solarpunk mentality.

Many people who have a semi-proficient understanding of how solarpunk works might say that the common aim is to create a utopian world.

In many ways, yes, that’s true. But we’ve come to know utopia as one step away from totalitarianism and dictatorship, and that’s not the place we want. The term utopia is actually from old Latin, and it can be “‘no-place’ (ou-topia) but also ‘good-place’ (eu-topia); implying a place so good it couldn’t exist”.

The goal then isn’t to create a place that’s perfect in every regard, it’s to create a good place, the eutopia of our dreams. A place where there is still sadness and heartache, but it’s not supplemented with suffering and despair. A good place is where people have food, water, shelter, and opportunity, and the solarpunk world will provide this with an environmentally-aware solution.

Birthing a Genre

Solarpunk started out as a concept that bounced back and forth between various thinkers. The first recorded use of the term was on a blog post “From Steampunk to Solarpunk” in 2008. After that, a number of writers, artists, and sci-fi enthusiasts developed the idea of solarpunk into the genre it is today.

In 2019, A Solarpunk Manifesto was published online, and it combined ideas from various other solarpunk tenets, but was by far the most solid definition of the genre. Among the fundamentals, A Solarpunk Manifesto states that “the genre provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.”

In this way, solarpunk differs from all other sci fi genres we’ve talked about. They aren’t concerned with the far future of space travel, or the technology of 100 years from now. Instead, solarpunks are dedicated in the near future, and the present. Solarpunk is less science fiction and more science possibility. Sure, not everything in solarpunk literature is factual, but it’s attainable at some point in the near future, which is more than we can say of a genre like space opera or biopunk.

List of Solarpunk Books

There are plenty of novels that fit into this niche now, despite being published thirty or forty years ago. Think of books like:

- The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach

- Orion Shall Rise by Poul Anderson

- Three California Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson

And then of course, we have a few different anthologies that really work to define the solarpunk genre and use the name as a banner for the future of sci fi.

- Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation edited by Phoebe Wagner and Brontë Christopher Wieland

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers edited by Sarena Ulibarri

- Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures edited by Christoph Rupprecht, Debora Cleland, Norie Tamura, Rajat Chauchuri, and Sarena Ulibarri

- Wings of Renewal: A Solarpunk Dragon Anthology edited by Claudie Arsenault and Brenda J. Pierson

Of course, other stand-alone books also fit the bill, stuff like:

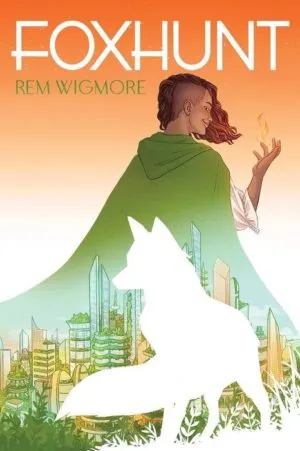

- Foxhunt by Rem Wigmore

- The Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn Johnson

- The Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

Films too can fall into the solarpunk basket, most notably including the work of Studio Ghibli with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and the representation of Wakanda in Black Panther.

All-in-all, I’d say that the solarpunk future that has been outlined in the Manifesto is attainable. It’s a goal that everyone should work toward, not just sci fi writers and scientists. More than any other genre, solarpunk seeks to create a time-bound, reasonable pathway for our sustainable future, and I think that is very admirable. After all, as stated in the manifesto, the genre “recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.”

If you liked this post, consider checking out some of our other posts about prominent sci fi subgenres.

And if you’re so inclined, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge, where you gain access to original science fiction from new and old authors alike, 6 times a year.

Sci fi Subgenres: Splice & Dice, the Biopunk Code

Of all the sci fi subgenres, biopunk probably hits the closest to home. Modern medicine and biotech has reached new heights, but a lot of the seeds of the fields were planted 40 years ago in some of the seminal biopunk novels.

Biopunk is closely related to cyberpunk and its derivatives, but it certainly presents a more realistic, while grim, outlook for our future.

What is Biopunk?

Where cyberpunk focuses on modifying the human body mechanically (think implants, advanced prosthetics, and computerized neuro functions), biopunk focuses on biology. Specifically, synthetic biology, including genetic engineering, extreme natural selection philosophies, and biochemical enhancement.

While some sci fi genres like solarpunk take a more optimistic outlook on the human experience, biopunk is closely related to cyberpunk in its adherence to a pessimistic, even grim, philosophy. As such, most biopunk books, novels, and games have dystopian societies, shadow governments, and totalitarian overtones.

Biopunk often features illegal black-market biohackers, people who operate outside the sanctioned scientific community to provide experimental—and dangerous—solutions to people’s troubles. While William Gibson’s Neuromancer was instrumental in the creation of cyberpunk, it also hinted at a biopunk world functioning in tandem with the flashy neon and advanced hardware of cyberpunk.

Case, the main character, sustained significant damage to his nervous system, which prevented him from hacking into cyberspace. In exchange for his services as a hacker, Armitage repairs his nervous system while implanting a failsafe—poison—in Case’s bloodstream. Biopunk, right?

It’s clear that biopunk doesn’t operate in a vacuum, but just how connected is it to real science? Well, this sci fi subgenre is simply a culmination of fear, anxiety, and contempt for the illicit activities of real-life scientists. The history of the biotechnology revolution laid the groundwork for the core tenets of the biopunk genre.

The Biotechnology Revolution

Biotechnology isn’t a new field. It’s predecessor, zymurgy, was incredibly prevalent in the late 1800s. The bustle and boom of the industrial revolution brought with it the need to increase food production and raise valuable capital for impending wartime projects.

German scientists began developing specific yeast strains that would increase beer production and boost the industry’s revenue. And during WWI, German and Russian scientists raced to use their new fermentation tech to support the war efforts, through the creation of hydraulic fluid alternatives and acetone.

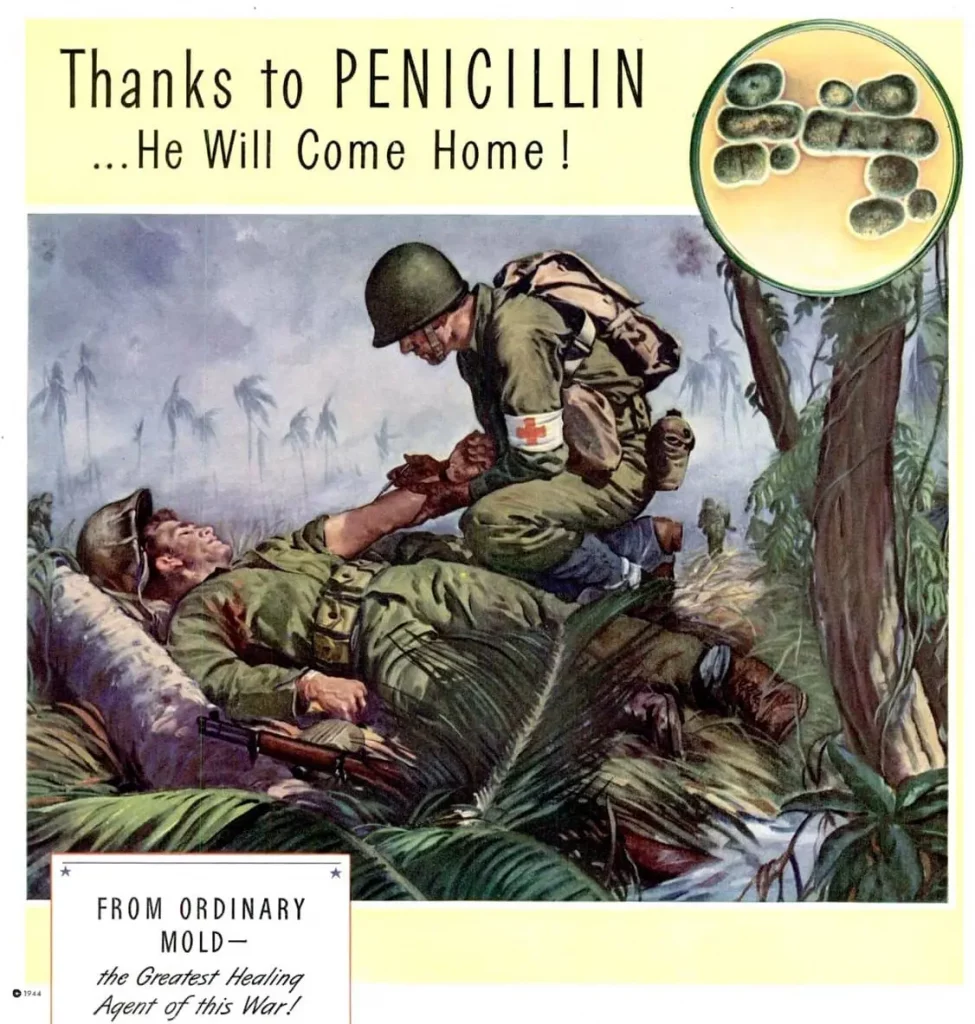

Eventually, the focus moved away from fermentation and the field was more broadly defined as biotechnology, coined by Karoly Ereky, a Hungarian pork mogul. With the discovery of penicillin, the field became obsessed with curing human ailments and making a stronger workforce.

After a few decades of tinkering with biofuel and single-cell protein projects, biotechnology experienced its next boom with the creation of genetic engineering. DNA structure and recombinant DNA took biotech by storm, and would remain the core focus of the field for the next fifty years.

Realizing the vast potential of biotechnology, politicians went to war with human rights activists over the ethics of biotech, and for a while the science community placed a moratorium on biotech until the industry was regulated and assuaged public fears.

The biotechnology as we know it today was born out of the desire to improve the human condition, with IVF, gene-editing therapy, and microbiological advancement like synthetic insulin.

But the biotechnology prominently featured in the biopunk genre is the biotech of the 1960s, which placed a heavy focus on eugenics and biological warfare.

Biopunk Novels, Films, and Games

One of the early proponents of the biopunk genre was Paul Di Filippo, with his collection of short stories, Ribofunk. Di Filippo emphasizes that cyberpunk as a genre lacks any real substance to maintain a status in the public eye for more than a fleeting moment. Instead, in Ribofunk, he proposes that biopunk, or slipstream works with a focus on biotech, is the study of living, not the depressing, close-to-extinction fiction of cyberpunk.

Despite his efforts to elevate the genre, much of biopunk still riffs off the dark nature of human experimentation and exploitation, albeit with some positive undertones.

Some prominent novels in the genre include:

- Blood Music by Greg Bear (often seen as an overlap of biopunk and nanopunk)

- The Xenogenesis trilogy by Octavia E. Butler

- Schismatrix by Bruce Sterling

- The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

But, the biopunk genre extends farther than the written word, encompassing visual mediums like film and video games.

- The BioShock game series

- The 2009 film Splice

- The Resident Evil game series

- The TV show Orphan Black

Blade Runner, the 1982 film based on Philip K. Dick’s book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is often categorized as a cyberpunk work, which in many ways, it is. However, it does feature biopunk themes. The Replicants, sometimes thought to be androids, are actually biologically-engineered, clone-like entities. This becomes clear in Blade Runner: 2049 with the scene Replicant-birth scene.

A Sci Fi Subgenre With Substance

Biopunk started out as an offshoot of cyberpunk, but in many ways, it has overshadowed its predecessor. The dedication to the ideological expansion of biotechnology and its implications to the everyday person makes biopunk a much more digestible genre than cyberpunk.

While we’re closely catching up to the cyberware featured in the cyberpunk arsenal, biopunk hits closer to home. Everyday we see incredible advancements in genetic engineering and biochemical panaceas that make biopunk’s darker ideations much more realistic and haunting.

What do you think? Will biopunk outlive its predecessor? Or will our biotech surpass the bounds of imagination?

Let us know in the comments below!

Sci Fi Subgenres: Fired Up On Dieselpunk

Of all the sci fi subgenres we’ve talked about here on Signals from the Edge, dieselpunk has to be one of the most fascinating.

It’s what many might call an in-between genre, seeing as how it falls right in the middle of steampunk and cyberpunk.

Where steampunk has a focus on Victorian and early industrialism technology, and cyberpunk is in a world of technological degradation and societal collapse, dieselpunk revels in the in-between space of prosperity and unrivaled growth.

What Is Dieselpunk?

The term Dieselpunk was first used in 2001 by game designer Lewis Pollack, who was describing his tabletop RPG game, Children of the Sun.

The aesthetics of dieselpunk were closely tied to those of steampunk, so many people that were fascinated with the era largely used that term.

However, as time went on, it became clear that the aesthetics and ideas of this sci fi subgenre were distinctly different from steampunk.

To summarize, Dieselpunk describes the time between World War I and the early 1950s. Historically, this period was filled with unprecedented economic failure, but it was also a time of surprising technological advancement, specifically with the development of diesel-powered vehicles.

Much of this technology can be accredited to the build-up to WWII, but dieselpunk takes these designs and ideas and puts a modern spin on them. Dieselpunk is also influenced heavily by jazz music and the Art Deco era.

Dieselpunk Derivatives

There are certain deviations on a theme within the Dieselpunk genre, and they are largely opposites.

The first distinction is what’s known as Ottensian dieselpunk, based of the ideas of Nick Ottens, a prominent author and ideologist within the genre.

Ottensian dieselpunk focuses on the post-WWI era. The aesthetics of the Roaring Twenties are paired with unbridled enthusiasm for a bright future. This kind of dieselpunk is hopeful and grand, heavily inspired by the Art Deco movement. Literature in this area of dieselpunk explores worlds that aren’t punctuated by the economic failure of 1929 or the subsequent Depression/War eras.

This contrasts severely with the dark, drab themes of Piecraftian dieselpunk, which is situated firmly in wartime eras. Piecraftian dieselpunk places a heavy focus on war-time technology, and speculates how humanity evolves—or ceases to evolve—if the world was locked in perpetual WWII-style conflict.

Many of the sentiments of the Dieselpunk genre might be seen as counterparts (or influenced by) the Lost Generation.

The Lost Generation and Dieselpunk

The Lost Generation refers to the group of young adults who were thrust into the first World War and emerged battered and disillusioned. Think Gertrude Stein, Hemingway, T.S. Elliot, etc.

Many of these writers exhibit what might be classified as Piecraftian sentiments. Even though their writing was primarily focused on the aftermath of worldwide conflict—and Piecraftian dieselpunk thrives on conflict—their ideas are connected.

Thinking about T.S. Elliot’s poem “The Wasteland”, the landscape of mass destruction matches the idea of a continuous war that impedes technological or societal growth. Even though a lot of “The Wasteland” can come off as bizarre to an untrained reader, the themes are clearly in line with the Piecraftian side of dieselpunk.

Dieselpunk In Literature, Art, and Gaming

While many other sci-fi subgenres appear in various mediums, none do so to the degree of dieselpunk (with the exception of cyberpunk, perhaps). Dieselpunk imagery and themes appear in art, cosplay, tabletop and video games as well as in films and novels.

Alternative history novels play a large role in establishing the dieselpunk genre. Think books like:

- The War That Came Early by Harry Turtledove

- SS-GB by Len Deighton

- Leviathan by Scott Westerfield

- Fatherland by Robert Harris

Newer books that take the themes of dieselpunk and run with them sometimes include fantastical elements or magic, things that contrast starkly with the grim, material nature of dieselpunk. Some of these books include:

- Ack-Ack Macaque by Gareth L. Powell

- Johannes Cabal the Necromancer by Jonathan L. Howard

- Lobster Johnson by Mike Mignola

- Amberlough by Lara Elena Donnelly

Dieselpunk takes a special place in the hearts of game developers, as the genre is vast playground for mechs, robots, tanks, and airplanes.

Games like Scythe and Crimson Skies bring dieselpunk to life on the tabletop. Video games too play a large role in this sci fi subgenre, with a long list of big titles falling on the aesthetics. These include:

- The Wolfenstein series

- Iron Harvest

- The Fallout series

- The Bioshock series

And of course, there is no lack of dieselpunk films/shows either. Popular titles include:

- The Man In The High Castle (series on Amazon Prime based on the books by Philip K. Dick)

- Captain America: The First Avenger

- Iron Sky

Some shows and movies operate on the fringes of dieselpunk. The Hunters show follows a similar vein as The Man In The High Castle, were the characters are hunting Nazis that escaped to America after WWII. And Indiana Jones is often said to have dieselpunk themes.

Wrapping Up This Sci Fi Subgenre Deep Dive…

Dieselpunk is certainly a rich and wide genre that continues to impress. Noir themes paired with post-war technology makes for an interesting and unique experience.

It’s worth noting that in deep corners of the internet, dieselpunk has a different following. Fashwave, a derivative of dieselpunk, has heavy anti-Semitic tones, and often punctuates dieselpunk imagery with fascist themes.

But, much of this doesn’t make it to the mainstream, and for now, dieselpunk remains a beloved genre amongst sci-fi enthusiasts.

If you liked this blog post, consider checking out some of our other content. At Signals from the Edge, we review new and old sci fi alike, interview authors, and explore the many themes and implications of all sci-fi subgenres.

Sci Fi Subgenres: An Introduction to Indigenous Futurisms

You might have heard of Afrofuturism, which is a popular literary and artistic movement that features work from the African diaspora. But have you heard of Indigenous Futurisms?

This sci fi subgenre promotes the work of Indigenous creatives, whether their work is written, visual, auditory, or a combination of both.

In this article, we’ll provide a brief introduction to the Indigenous Futurisms movement and give you some resources so you can learn more!

What Is Indigenous Futurisms?

Indigenous Futurisms, a term coined by Dr. Grace Dillon, refers to the movement by Native peoples to define their future and reconcile their past through speculative fiction.

Much like the Afrofuturism movement, Indigenous Futurisms is an intersection of past and present, technology and cultural heritage.

Johnnie Jae, a member of the Otoe-Missouria and Choctaw Tribes of Oklahoma and the founder of A Tribe Called Geek, says that for her, Indigenous Futurisms is a counterpart to traditional science fiction. Where traditional science fiction presents visions of colonization and violence, Indigenous Futurisms operates on the rule that “the advancement of technology doesn’t [need to] disrupt or destroy ecosystems or the balance of power between humans and nature.”

In many ways, the core tenants of Indigenous Futurisms literature correspond with the ideas of other sci fi subgenres like solarpunk and biopunk. These sectors of science fiction focus on integrating technology with the environment, and using tech as a means to restore life to what we have destroyed. The idea of a harmony between science and nature is something that has fascinated sci fi writers for years.

Indigenous Futurisms and the Apocalypse

While the Indigenous Futurisms movement strives to focus on the future of technology and nature, it’s undeniable that the genre is deeply tied to the past.

And how can it not be? Since European explorers landed in the Americas at the turn of the 15th century to about 1700, the population of Native peoples declined by as much as 95 percent.

Imagine being the remaining 5 percent of the population, having witnessed massive death at the hands of European violence and disease. It would be like living in a post-apocalyptic world, where your survival meant that you were going to be subjected to, perhaps the even more cruel, hand of colonialism.

If slavery and discrimination are proponents of Afrofuturism, then genocide and institutional colonialization are so for Indigenous Futurisms.

Indigenous Futurisms and Developing Sovereignty

One of the big themes of Indigenous Futurisms is the idea of building sovereignty through fiction.

Because of colonialism, Native sovereignty was almost completely eradicated, and those that survived the 19th century, began to work toward regaining a semblance of their past freedoms. But they were faced with harsh sentiment and stereotyped into a box. The appearance of Native American identity wasn’t even crafted by Native people, but instead by the media, racism, and the overall imperialistic nature of American society.

Indigenous Futurisms allows Native Americans to have a space that exists outside the reservations and the stereotypes that paint them as tribal traditionalists, while at the same time exploring the intricacies of their cultural heritage. This freedom to create and operate in a space of both tradition and an individuality is what Indigenous Futurisms is about. As Rebecca Roanhorse says, it’s about “advocate[ing] for the sovereign”.

So how does sovereignty come about from Indigenous Futurisms?

It’s not a rewrite of history. The movement isn’t about changing the past. It’s about changing the future and setting the story straight.

One of the greatest examples of the development of individual sovereignty comes from Roanhorse’s 2016 novel, Trail of Lightning.

Maggie Hoskie, the badass monster-hunting protagonist, embarks on a journey across a post-apocalyptic landscape to save her homeland.

Her journey of discovery is separate from an identity of tribal community, but is also steeped in cultural tradition because her heightened abilities have origins in her tribal identity. Maggie Hoskie’s storyline moves parallel to the development of the community in Trail of Lightning, but does not necessarily intersect because she is considered to be an outcast. Her sovereignty is developed through her solitude, but by the end of the story, she is no longer the solo hunter, but a part of a team working to save Dinetah.

Maggie’s story mirrors what Elizabeth LaPensee says about sovereignty in a round table discussion from Strange Horizons. She says “Sovereignty in media means self-determined work and collaborations with communities that are by us (if needed, with help from genuine allies who really listen), primarily for us.”

A Movement for the Future

Overall, the historical legacy of colonialism in America still glares through in Native American contemporary speculative fiction, but it has been subverted. Apocalypse has laid like a shadow over the Native American people for generations, and that too finds its way into the Indigenous Futurisms movement. However, the subversions of these legacies allow Native authors to stake their claim and develop their sovereignty.

Trail of Lightning presents the narrative of the individual running parallel to the cultural community in a way that is not steeped in stereotypes. In the end, the Indigenous Futurisms movement is steeped in both cultural tradition but a looking-forward mentality that gives Native Americans a space to combat the tropes that have been spread about their traditions and at the same time present a future where they aren’t victims, but sovereigns in their own right.

Understanding Sci Fi Subgenres: Gothic Science Fiction

Aaaand we’re back to break down more sci fi subgenres, this time we’re delving into the creepy, weird world of gothic science fiction!

For many people, hearing the words ‘gothic science fiction’ brings back memories of high school English class and Mary Shelley’s magnum opus, Frankenstein.

And certainly, Frankenstein is one of the pinnacle works in this sci fi subgenre, but it also largely inspired the genre as we know it today.

What is Gothic Science Fiction?

Gothic science fiction sits in that liminal space between two genres. On one hand, it takes a lot of aesthetics and themes from traditional gothic fiction, and on the other hand, it incorporates controversial or untested sciences to push the boundaries of creepy.

Gothic fiction dates back to the late 1700s and early 1800s, but has remained a steadfast genre to modern day. Where Horace Walpole, Mary Shelley, Eleanor Sleath, and Samuel T. Coleridge put the arcane into writing by candlelight, authors like Toni Morrison, Steven King, and Joyce Carol Oates brought the supernatural into the electric-light of modernity.

One of the staples of Gothic fiction has always been a fascination with the mysterious and the unexplainable. In Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764), a massive helmet falls from the sky to kill one of the characters, and skeletal apparitions walk the castle halls at night. In many ways, the supernatural in Gothic fiction motivates characters to say and do things they might not normally do. Pure fear and confusion drive them to the ends of their wits, and this terror of human uncertainty is what makes Gothic fiction unique.

In modern horror, yes, motivations are driven by fear, but ultimately the unexplainable and the mysterious are more than just a catalyst. They’re a key component in the reaction of the reader or viewer.

Think of it like the difference between a jump scare and a lingering fear. When a demon or a ghoul lurches abruptly onto the screen, the audience lets loose a scream of horror. But when the fear builds up across the whole book or novel, it leaves the audience unable to sleep at night, unsettled even in the security of their own home.

The 2017 IT movie makes use of the jump scare, whereas something like The Telltale Heart employs an exponentially-growing fear that lingers even after the last page.

Other conventions of Gothic fiction include:

- Medieval or ancient settings (castles, old churches, ancient barrows, etc.)

- An emotional response (the lingering fear brought on by what Edmund Burke describes as the Sublime)

- Political or sociopolitical undertones (The Mask of Anarchy by Percy Shelley pairs Gothic themes with a plea for nonviolent resistance)

Putting the Science in Goth Science Fiction

While the occult and the supernatural play a large part in defining traditional Gothic fiction, the addition of science takes the genre to new heights.

Take Frankenstein, for example. Most of what makes the story compelling is the deep moral quandary and tragedy of Victor Frankenstein, brought on by his dabbling in arcane sciences, namely the reanimation of dead tissue. Shelley’s use of science in Frankenstein is a vehicle for plot progression, and largely a catalyst for her character’s ongoing psychosis.

Vampirism is another good example. There are two sides to the same coin.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1897, brought vampires into the limelight. In a traditional Gothic sense, vampires are creatures of folklore, hearkening back to medieval eras. The story of the 2014 film Dracula Untold follows in Stoker’s footsteps, with the source of horror coming from an ancient creature, presumably Nosferatu. Science has no part in the film.

But, in a Gothic science fiction sense, vampirism might be defined as a genetic or blood disease rather than a result of the supernatural. Renfield Syndrome is the clinical definition we use today to describe an all-encompassing obsession with blood. The condition was named after a character in Stoker’s book.

Using science as an explanation for the occult might seem like a visible deconstruction of the Gothic genre, but in many ways it elevates the elements of horror.

Today, reading Dracula or Frankenstein by itself with no adjacent literature to define them, they seem a bit less scary than they probably were a hundred years ago. They are rooted in a fear of the unexplainable, and use that fear as a vehicle for plot.

This is because modern science and all of its tools are able to help explain some of the phenomena found in traditional Gothic novels (aside from, perhaps, helmets falling from the sky).

The unexplainable is no longer so foreign anymore, is it? Vampirism isn’t the result of an arcane horror, but rather a disease we can define in clear terms. Apparitions can be explained as unique phenomena based on environment, atmospheric conditions, etc. etc.

Taking this Scully-ish approach breaks down the key mechanism of Gothic fiction which is the fear of the unknown. So how do we keep a genre alive when its kingpin tactic has been jeopardized?

What Makes Gothic Science Fiction?

You might be thinking, ‘Gothic fiction still stands today because people are still scared of the unknown’ and you’d be right. As viewers, we can appreciate the Gothic genre for what it is, and I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t creeped out by The Castle of Otranto or “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow”.

What I’m proposing is that Gothic science fiction is the evolution of Gothic fiction, that this sci fi subgenre is an adaptation of traditional themes meant to appeal to a modern audience.

As a modern reader, the difference between the 1897 Dracula and the 1954 I Am Legend is that Matheson incorporates the idea of the occult—vampirism—and skews it in a science fiction way. In 2021, where electric light and technology reach even to the deepest corners of our lives, a vampiric pandemic inspires more fear than whatever arcane horror might be lurking in ruined castles.

The potential for a widespread blood-sucking, zombifying disease seems a lot more plausible than stuff of folklore because it preys on our fear of the scientific unknown. By that I mean that for those of us that lack the scientific literacy to explain a vampiric disease, it serves the same purpose as any other mysterious Gothic fears we don’t understand.

The core tenant of Gothic fiction is the unexplainable, but our definition of the unexplainable has changed from 200-hundred years ago. And that’s where science comes into play, because the vast majority of us can’t explain how vampiric diseases, the fabric of reality, or extraterrestrial phenomena work. For the viewer, the new unexplainable is on the fringes of science.

In Conclusion

I guess something that occurred to me while writing this is that Gothic science fiction doesn’t seem to have a linear timeline. There isn’t a “this was the first book ever written and here’s the most recent”. It’s a theme that can be transposed on many works, even if they were written a hundred years apart.

At the end of the day, what Frankenstein and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde started, modern science fiction authors modify to keep up with the pace of technological and scientific advancement.

Everyday the bounds of the unknown get pushed farther back, and the Sublime morphs to account for the forward march of science.

As one of the prominent sci fi subgenres, Gothic science fiction continues the tradition of putting into words what we think about at the darkest hour of night.

Honing in on Sci Fi Subgenres: Space Westerns

Space westerns are probably one of the most fun sci fi subgenres out there. They pair the aesthetics and ideals of traditional westerns with the flash and bang of science fiction.

While the genre isn’t a huge one, there are some notable TV shows and films as well as book and comic books in the genre. Maybe you know a few!

But, the misconception that without cowboy hats and gunslingers, a piece isn’t a space Western is largely flawed. Many conventions of the Western film or comic book have made their way into modern science fiction and influenced its storytelling. You may have seen a movie and not even realized it’s roots in Western cinematography.

The Origin of the Space Western

The space western is the love child of two different genres: sci fi and the western. Westerns are sometimes considered a speculative fiction, though traditional Westerns are down to earth, without aspects of science fiction, fantasy, or the paranormal.

Space westerns actually got their roots in early American comic books. C.L. Moore, one of the early female science fiction writers, created the character of Northwest Smith who popularized the planet-jumping, gunslinging, space cowboy.

In the early 1940s, superhero comic books became less popular, so to fill the void, publishers started pairing Western stories with science fiction ones, and the line between the genres was slowly erased.

However, the space western really came to the limelight with movies like Star Trek and Star Wars as well as with shows like Firefly and Cowboy Bebop.

Types of Space Westerns

So as I’ve seen it there are a couple different ways we can break down kinds of space westerns as a sci fi subgenre.

First there are the science fiction films that employ classic Western-style story structure.

Star Trek is a good example, where the vast universe acts as the untamed West, the final frontier. It’s about adventure and chivalry, both of which are Western themes. Prospect is another good example of a space western film. It pairs the story elements of a Western with the setting and conflicts of a sci-fi world.

Second, there are Western films that integrate science fiction. Think of the film Westworld, and the later TV show as well. The characters aren’t in space, it’s not a space opera, but it pairs the aesthetics of the Western with modern science fiction.

And the final distinction I’ve made is a healthy mix of the two genres. Firefly and Serenity are my prime examples of this sci fi subgenre. The wardrobe, weaponry, slang, and storytelling tone of Firefly places it firmly in the Western genre. But, the space ships, interplanetary travel, and alien creatures root it in science fiction.

However, these two seemingly polar opposites come together as a seamless piece. When watching Firefly, I never felt like I was torn between one setting or another. There was nothing amiss, and that’s exactly how a good science fiction should operate.

image from The Verge

Characteristics of a Space Western

Thinking about this topic made me come up with a checklist of characteristics that make up a space western. There aren’t many, but they’re distinct.

- A strong lead character, often physically adept and righteous. Much like a white-hat cowboy.

- An animal sidekick. In many Westerns, this is the hero’s horse, but it can manifest as other things. R2-D2, for example, might be Luke’s horse equivalent. Or Ein, the Welsh corgi from the space Western anime, Cowboy Bebop.

- Western literature has popularized the outlaw character, the rogue. Picture characters like Han Solo.

- Wide, aesthetic shots. In space Western films and shows, wide landscape shots or panning scenes hark back to classic Western cinematography like in A Fistful of Dollars. A more modern example might be the director’s cut of Logan, which turns the film black and white.

image from Entertainment Weekly

Space Westerns That Are Still Riding Into The Sunset

The space western genre does for me something that traditional Westerns have failed to do, which is to bring the genre up to speed.

Watching old Western films is enjoyable, don’t get me wrong, but sometimes the outdated habits or cliches make them uncomfortable to watch. Let’s just say some of them haven’t aged well.

But, space Westerns, at least some of the modern ones, hand out that gunslinging hero candy like it’s Halloween, without having to worry about getting sick from too much chocolate. I love Firefly, and yes there are some things I’d change about it, but I find it more palatable than a classic Western from the days of the Silver Screen.

And I love seeing the conventions of the space Western make their way into other sci fi subgenres, like space opera. The Expanse operates a lot like Firefly, but without the brown trench coats and Colt-esque revolvers.

All in all, space Westerns bring the best parts of both Western and science fiction together into a unique mesh of styles. I’m excited to see what the next few years brings for the genre.

If you liked this post and want to see more content about sci fi subgenres, leave a suggestion in the comments down below!

Classic Military Science Fiction Books by Veterans

Calling all sci-fi enthusiasts to the bridge!

Military science fiction has been a staple of the genre since the inception of science fiction. Intergalactic wars, space robots, lasers—the whole nine yards. But, sometimes military sci-fi can get a bit fanciful, and feels less science, more fiction.

In this article, we’ll discuss four military science fiction books by veterans, and how their real-life experiences influenced their writing.

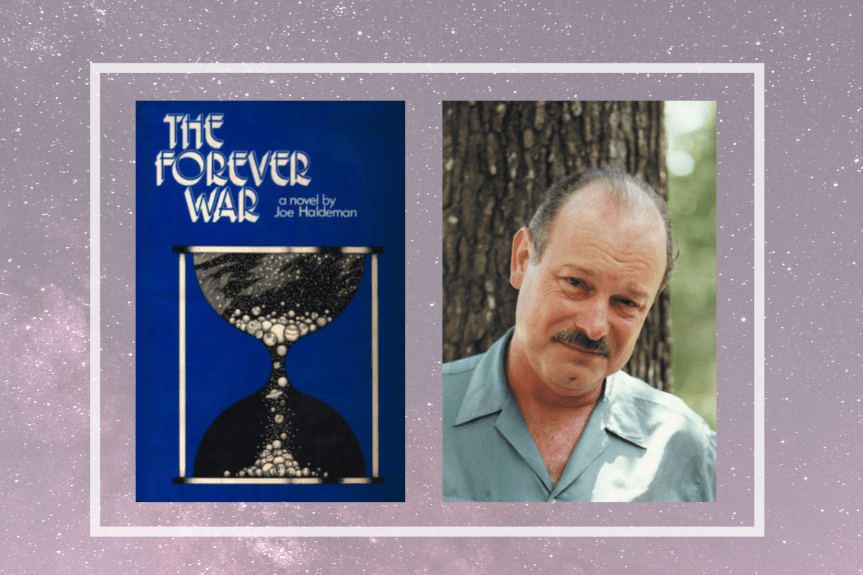

- The Forever War by Joe Haldeman

- Up the Walls of the World by James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Bradley Sheldon)

- The Healer’s War by Elizabeth Ann Scarborough

- The Mercenary by Jerry Eugene Pournelle

The Forever War by Joe Halderman

The Forever War is a science fiction novel written by American writer Joe Haldeman, published in 1974. The book is about a group of human soldiers battling against an alien civilization known as the Taurans.

The book won the Nebula Award in 1975 and the Hugo and Locus Awards in 1976.

Joe Haldeman is well-known for several best-selling science fiction novels, such as The Hemingway Hoax (1990) and Forever Peace (1997), and of course, The Forever War.

He was born in Oklahoma on July 9th, 1943. He is currently married to Gay Haldeman.

Halderman was drafted into the US Army during the Vietnam War. Many of his experiences overseas influenced his writing, and after the war he went on to get an MFA in creative writing from the University of Iowa.

Halderman has been the president of the Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) twice and is currently an adjunct professor teaching writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Up the Walls of the World by James Tiptree Jr. (Alice Bradley Sheldon)

Up the Walls of the World is a science fiction novel written by American writer and feminist Alice Sheldon, who goes by the pseudonym James Tiptree Jr., published in 1978.

The book explores telepathy and other psychic phenomena in the face of an alien invasion from the planet Tyree.

Up the Walls of the World was nominated for the Hugo Award in 1979. However, the nomination was withdrawn by the author.

Alice Sheldon was born in Chicago in May, 1915, and passed away in May, 1987. She was married to William Davey in 1934, got divorced from him in 1941, and then married Huntington D. Sheldon, with whom she had three children.

In 1942, Alice joined the US Air Force as an intelligence officer, analysing aerial photographs of enemy territory. After WWII, she joined the CIA for a time before furthering her education at American Unioversity and George Washington University.

Over the course of her career, she won a Hugo Award, a Jupiter Award, and a Nebula Award thanks to her eclectic novels and short story collections.

The Healer’s War by Elizabeth Ann Scarborough

The Healer’s War is a science fiction novel written by American writer Elizabeth Ann Scarborough, published in 1988.

The book narrates the story of Lieutenant Kitty McCulley, an inexperienced young nurse trying to help horrendously damaged Vietnamese soldiers and civilians while battling on her own against overt racism amongst her colleagues.

Elizabeth Scarborough was born in Kansas in March, 1947. Her best-selling novel The Healer’s War earned her a Nebula Award in 1989.

Elizabeth worked as an RN in the US Army for five years and served in Vietnam during the eponymous war. Many of her experiences during the war are reflected in The Healer’s War.

Today, she is an active novelist, having published over 45 original novels and many more short stories.

She now publishes the bulk of her independent work through Gypsy Shadow Publishers.

The Mercenary by Jerry Eugene Pournelle

The Mercenary is a science fiction novel written by American writer Jerry Pournelle, published in 1972.

The book is a part of a larger series, Falkenberg’s Legion. The series follows John Christain Falkenberg as he assembles force to protect Earth from extraterrestrial threats. The novel was nominated for the Hugo Award but did not get it.

Jerry Pournelle was born in Louisiana in 1933, and passed away in 2017. Pournelle never won a Hugo Award, stating that “money will get you through times of no Hugos, but Hugos won’t get you through times of no money”.

Pournelle served in the US Army during the Korean War, and later went on to get a Ph.D. in political science. Pournelle married Roberta Jane Isdell and had five children, who have also written science fiction in collaboration with their father.

He wrote numerous publications that later on were used by the US Military and Air Force Academies and the Native and Air War Colleges. He also served a term as SFWA president.

While these classic military science fiction books just scratch the surface of the genre, they are a pretty good starting place. What military sci-fi books do you like? Let us know in the comments below.