So, I have to be honest, I’ve been doing a lot of research into what makes particular sci fi subgenres tick. After writing about the solarpunk genre a few weeks ago, something didn’t sit right with me.

After doing some more reading, I’ve pinpointed a few issues with the idea of solarpunk, at least, with how it’s been previously defined.

This goes back to the idea of the punk—the social deviant and system-breaker—and how that really applies to these genres. In the “good-place” utopia that solarpunk strives to be, where does the punk come into play?

And what is lunarpunk? The dichotomous relationship with solarpunk really sets up a whole new perspective that opens up how we can look at the genres.

Problems With Solarpunk

One of the primary things I find a bit troubling about solarpunk as an ideology is the insertion of the ‘punk’. Now, previously, I had defined the solarpunk as being someone who “cares a lot less about rebelling against a system that impacts them as an individual, but instead takes a more environmental approach. They are eco-activists who aim to right the wrongs of the past with technology that is sustainable and renewable.”

On the surface level, I think this is still true. It’s an easy way to define the general mindset of the solarpunk in fiction, and in reality.

However, I overlooked the fact that solarpunk is so dedicated to the creation of a unified collective, that the ‘punk’ might end up slipping out of this collective. You simply can’t have a collective of punks, because that’s counterintuitive on two fronts. So where does the punk fit in a utopia they helped to create? Does the cycle continue after the ideal world has been achieved? What point is there in a rebellion when all is seemingly good?

To rectify this little oversight, we don’t have to completely rework the philosophy of the genre, we simply have to break it up.

We can look at it in three stages:

Three Stages of Solarpunk

Pre-solarpunk is (hopefully) the current state of the world today, in 2022. The climate crisis is getting worse by the day, biodiversity is rapidly deteriorating. But, the fundamentals of change are happening. You’re reading this blog, people are writing eco-fiction and using their skills to work toward a sustainable future.

Solarpunk really picks up when change is acted upon in radical ways. When rebellions begin and oppressive systems are picked apart. This stage is revolution, where the punks take their stand and worldwide change comes to fruition.

Post-solarpunk is really where a lot of the literature defined as “solarpunk” fits in. This stage is when the revolution has been completed, and the systems in place are all working together toward the “good-place” utopia. There will still be problems, sure, but the radical nature of the punk as defined by the revolution stage is no longer condoned. The system in post-solarpunk gets as close to the perfect, sustainable world as possible.

In the post-solarpunk world, I might venture so far as to define the punks as philosophical solar-anarchists. These people aren’t radicalized to the point of revolution (because their revolution has already occurred) but they still operate on the fringes, working against systems they deem as oppressive, or ones that might become oppressive. Traditional philosophical anarchists defy social order and state control, with the ultimate goal of freeing the individual from oppressive systems.

We might think of the post-solarpunks as being the watchers on high of the new society. The systems that replaced the capitalist regime are still a step away from true self-governance, but the post-solarpunks tolerate the new system.

Where Does Lunarpunk Come In?

Lunarpunk is the other side of the solarpunk coin. It’s a very new genre, and it’s more rooted in aesthetics and spiritualism than solarpunk is. While you might be able to skew solarpunk as a political ideology, lunarpunk is much harder to pin down.

No one person has been accredited with the creation of lunarpunk, but there are quite a few people on the Internet that have contributed to the philosophy of the genre.

In an expansive Tumblr comment from thecarboncoast, lunarpunk is defined loosely as:

“Aspeculative fiction style/genre defined by an obscured, shrouded, and/or dark near-future where the business of its inhabitants is done in secretive, cryptic or mysterious ways, accentuated by a visual style hearkening to lunar, occult, Pagan, Wiccan, Satanic, Anarchaic, Chaotic, practices, and comprised of world-building details which are more ideal for introverted, quiet, isolated or self-reliant people. Doesn’t mean an extroverted Christian isn’t part of Lunarpunk, or that someone who practices anything mentioned above isn’t part of Solarpunk. But in terms of what defines Lunarpunk as a genre, you would be more likely to see small sects of persons worshiping (or devoting to) The Self rather than The Other.”

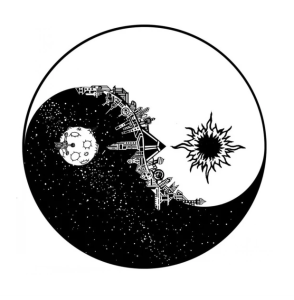

So, it’s clear the lunarpunk operates side-by-side with solarpunk, with a duality that’s often characterized by the yin and yang symbol. The presence of spirituality as a defining feature is really what seperates lunarpunk from solarpunk.

Where solarpunk is a calculating genre that places a focus on the breakdown of societal structures—politics, religion, media, etc.—lunarpunk embraces the loose structure of spirituality and champions individuality.

Instead of a focus on the technology and practices for advancing society, lunarpunk is more about creating a more sustainable sense of self.

One way I’ve seen this concept described is that the sun represents the consciousness, while the moon represents the subconsciousness. It makes sense, primarily because lunarpunk revels in the unexplainable, while solarpunk focuses on reality.

Can There Be a Solarpunk Without Lunarpunk?

Part of the reason I was troubled by solarpunk was because there seemed to be a loss of the individual. Sure, individuals are the ones behind great ideas for sustainable technology, and a more accepting society allows people to be who they want to be.

But the individual is always talked about in connection to society, and that, even in a punk sense, isn’t what individual means.

After learning about lunarpunk, I realized that the two genres must coexist together, lest they both evaporate. Lunarpunk accounts for the individual outside of the societal sphere. Spirituality is largely an individual journey, and lunarpunk’s secretive, mysterious nature supports the development of individual politics and spirituality.

In this regard, I think that the “punk” in lunarpunk is about breaking away from society, no matter how green and pure and optimistic it may be. The dichotomy of solarpunk/lunarpunk levels both of the genres out. There’s a balance that’s necessary for survival. Focus on solarpunk for too long, you lose sight of who you are for the greater good of the society, and if you focus on lunarpunk for too long, you become isolated and disconnected from others.

And to answer the titular question: yes, I think lunarpunk succeeds in solving some of solarpunk’s problems. Not all of them, but those are bound to work themselves out as the two genres converge and grow together.