Every day there’s a new environmental disaster on the news, or a new forecast for when climate change will reach critical mass. All of the impending doom features can leave you feeling down and out, hopeless in a stark grey world.

But not everything has to be so grim. Solarpunk, a relatively new branch of science fiction, aims to bring some light to the otherwise dark future. Solarpunk technology and ideologies paint a picture of sustainability and equality, a future where art, science, and nature coexist in the same spaces.

What Is Solarpunk?

We talked about solarpunk a bit in a different blog post where we discussed the punk sci fi subgenres, but we’ll elaborate a bit more here.

Where genres like cyberpunk are characterized by an overarching pessimism about our futures, solarpunk seeks to instill some hope into those visions of the future. Cyberpunk is about how technology impacts the human existence, with a focus on hardware modifications. And biopunk is all about how biology can improve the human condition, with a focus on genetic editing.

In both of those genres, the idea of the ‘punk’ is someone who is culturally or ideologically deviant from a perceived norm. Where ‘punks’ as we know them today are stereotyped as people who skateboard, die their hair, and pierce their nose, the punk of the cyberpunk/biopunk world takes body modification to the next level.

This kind of punk breaks the conventional norms of the body. The solarpunk cares a lot less about rebelling against a system that impacts them as an individual, but instead takes a more environmental approach. They are eco-activists who aim to right the wrongs of the past with technology that is sustainable and renewable.

Solarpunk, perhaps more than any other genre, can act as a political mindset. Because of the environmental focus, it almost inherently comes off as an anti-capitalist—sometimes anarchist—genre.

In essence, solarpunk as a genre is a realistic, hopeful glimpse into a future that’s powered by sustainable practices and inclusivity.

The Solarpunk Mission: Reach Eutopia

So, we know that solarpunks want to improve our futures by using technology that’s available to them, but are also eco-conscious and deviant from the societal norms. This means that we can see a lot of off-the-wall, genius ideas coming from people who ascribe to the solarpunk mentality.

Many people who have a semi-proficient understanding of how solarpunk works might say that the common aim is to create a utopian world.

In many ways, yes, that’s true. But we’ve come to know utopia as one step away from totalitarianism and dictatorship, and that’s not the place we want. The term utopia is actually from old Latin, and it can be “‘no-place’ (ou-topia) but also ‘good-place’ (eu-topia); implying a place so good it couldn’t exist”.

The goal then isn’t to create a place that’s perfect in every regard, it’s to create a good place, the eutopia of our dreams. A place where there is still sadness and heartache, but it’s not supplemented with suffering and despair. A good place is where people have food, water, shelter, and opportunity, and the solarpunk world will provide this with an environmentally-aware solution.

Birthing a Genre

Solarpunk started out as a concept that bounced back and forth between various thinkers. The first recorded use of the term was on a blog post “From Steampunk to Solarpunk” in 2008. After that, a number of writers, artists, and sci-fi enthusiasts developed the idea of solarpunk into the genre it is today.

In 2019, A Solarpunk Manifesto was published online, and it combined ideas from various other solarpunk tenets, but was by far the most solid definition of the genre. Among the fundamentals, A Solarpunk Manifesto states that “the genre provides a valuable new perspective, a paradigm and a vocabulary through which to describe one possible future. Instead of embracing retrofuturism, solarpunk looks completely to the future. Not an alternative future, but a possible future.”

In this way, solarpunk differs from all other sci fi genres we’ve talked about. They aren’t concerned with the far future of space travel, or the technology of 100 years from now. Instead, solarpunks are dedicated in the near future, and the present. Solarpunk is less science fiction and more science possibility. Sure, not everything in solarpunk literature is factual, but it’s attainable at some point in the near future, which is more than we can say of a genre like space opera or biopunk.

List of Solarpunk Books

There are plenty of novels that fit into this niche now, despite being published thirty or forty years ago. Think of books like:

- The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Ecotopia by Ernest Callenbach

- Orion Shall Rise by Poul Anderson

- Three California Trilogy by Kim Stanley Robinson

And then of course, we have a few different anthologies that really work to define the solarpunk genre and use the name as a banner for the future of sci fi.

- Sunvault: Stories of Solarpunk and Eco-Speculation edited by Phoebe Wagner and Brontë Christopher Wieland

- Glass and Gardens: Solarpunk Summers edited by Sarena Ulibarri

- Multispecies Cities: Solarpunk Urban Futures edited by Christoph Rupprecht, Debora Cleland, Norie Tamura, Rajat Chauchuri, and Sarena Ulibarri

- Wings of Renewal: A Solarpunk Dragon Anthology edited by Claudie Arsenault and Brenda J. Pierson

Of course, other stand-alone books also fit the bill, stuff like:

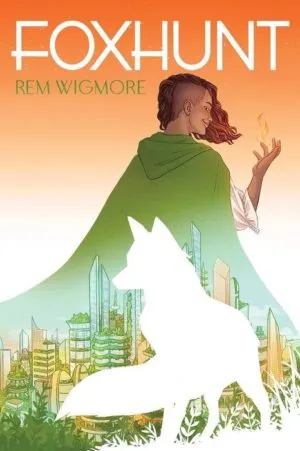

- Foxhunt by Rem Wigmore

- The Summer Prince by Alaya Dawn Johnson

- The Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers

Films too can fall into the solarpunk basket, most notably including the work of Studio Ghibli with Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and the representation of Wakanda in Black Panther.

All-in-all, I’d say that the solarpunk future that has been outlined in the Manifesto is attainable. It’s a goal that everyone should work toward, not just sci fi writers and scientists. More than any other genre, solarpunk seeks to create a time-bound, reasonable pathway for our sustainable future, and I think that is very admirable. After all, as stated in the manifesto, the genre “recognizes science fiction as not just entertainment but as a form of activism.”

If you liked this post, consider checking out some of our other posts about prominent sci fi subgenres.

And if you’re so inclined, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge, where you gain access to original science fiction from new and old authors alike, 6 times a year.