Of all the sci fi subgenres, biopunk probably hits the closest to home. Modern medicine and biotech has reached new heights, but a lot of the seeds of the fields were planted 40 years ago in some of the seminal biopunk novels.

Biopunk is closely related to cyberpunk and its derivatives, but it certainly presents a more realistic, while grim, outlook for our future.

What is Biopunk?

Where cyberpunk focuses on modifying the human body mechanically (think implants, advanced prosthetics, and computerized neuro functions), biopunk focuses on biology. Specifically, synthetic biology, including genetic engineering, extreme natural selection philosophies, and biochemical enhancement.

While some sci fi genres like solarpunk take a more optimistic outlook on the human experience, biopunk is closely related to cyberpunk in its adherence to a pessimistic, even grim, philosophy. As such, most biopunk books, novels, and games have dystopian societies, shadow governments, and totalitarian overtones.

Biopunk often features illegal black-market biohackers, people who operate outside the sanctioned scientific community to provide experimental—and dangerous—solutions to people’s troubles. While William Gibson’s Neuromancer was instrumental in the creation of cyberpunk, it also hinted at a biopunk world functioning in tandem with the flashy neon and advanced hardware of cyberpunk.

Case, the main character, sustained significant damage to his nervous system, which prevented him from hacking into cyberspace. In exchange for his services as a hacker, Armitage repairs his nervous system while implanting a failsafe—poison—in Case’s bloodstream. Biopunk, right?

It’s clear that biopunk doesn’t operate in a vacuum, but just how connected is it to real science? Well, this sci fi subgenre is simply a culmination of fear, anxiety, and contempt for the illicit activities of real-life scientists. The history of the biotechnology revolution laid the groundwork for the core tenets of the biopunk genre.

The Biotechnology Revolution

Biotechnology isn’t a new field. It’s predecessor, zymurgy, was incredibly prevalent in the late 1800s. The bustle and boom of the industrial revolution brought with it the need to increase food production and raise valuable capital for impending wartime projects.

German scientists began developing specific yeast strains that would increase beer production and boost the industry’s revenue. And during WWI, German and Russian scientists raced to use their new fermentation tech to support the war efforts, through the creation of hydraulic fluid alternatives and acetone.

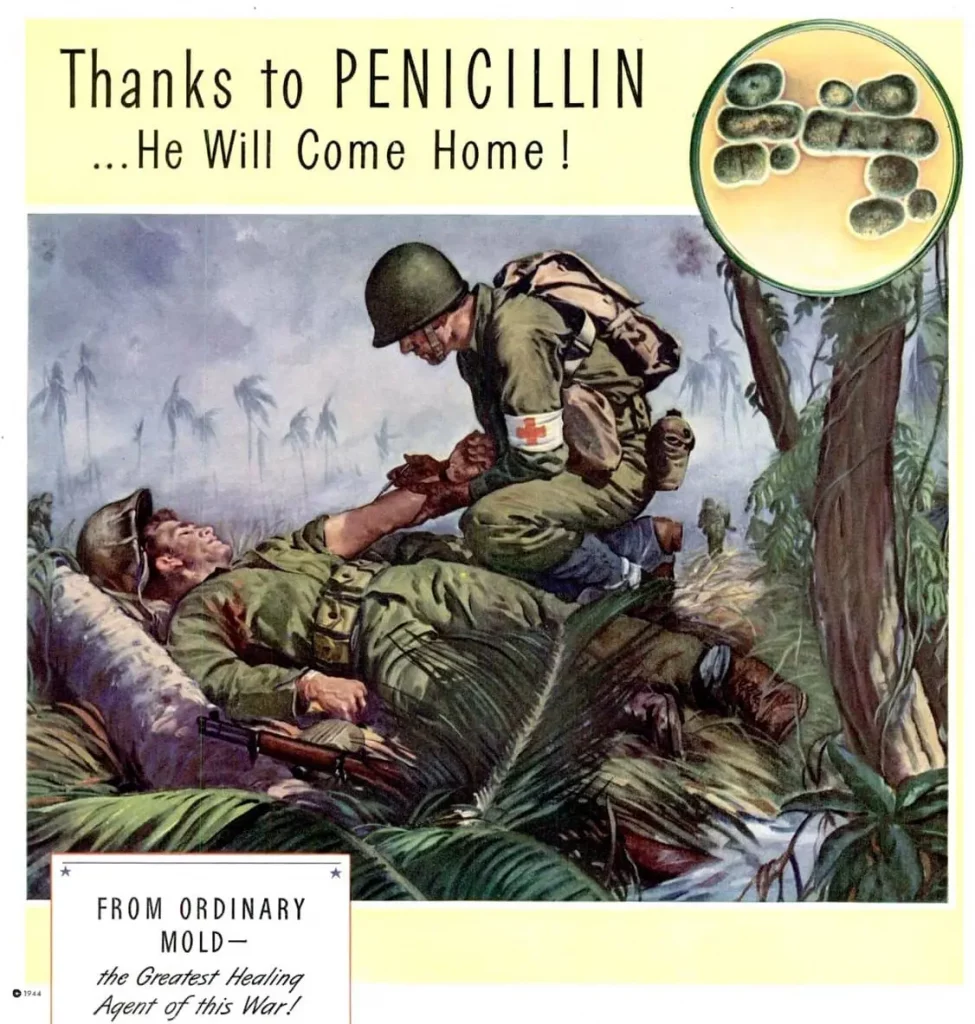

Eventually, the focus moved away from fermentation and the field was more broadly defined as biotechnology, coined by Karoly Ereky, a Hungarian pork mogul. With the discovery of penicillin, the field became obsessed with curing human ailments and making a stronger workforce.

After a few decades of tinkering with biofuel and single-cell protein projects, biotechnology experienced its next boom with the creation of genetic engineering. DNA structure and recombinant DNA took biotech by storm, and would remain the core focus of the field for the next fifty years.

Realizing the vast potential of biotechnology, politicians went to war with human rights activists over the ethics of biotech, and for a while the science community placed a moratorium on biotech until the industry was regulated and assuaged public fears.

The biotechnology as we know it today was born out of the desire to improve the human condition, with IVF, gene-editing therapy, and microbiological advancement like synthetic insulin.

But the biotechnology prominently featured in the biopunk genre is the biotech of the 1960s, which placed a heavy focus on eugenics and biological warfare.

Biopunk Novels, Films, and Games

One of the early proponents of the biopunk genre was Paul Di Filippo, with his collection of short stories, Ribofunk. Di Filippo emphasizes that cyberpunk as a genre lacks any real substance to maintain a status in the public eye for more than a fleeting moment. Instead, in Ribofunk, he proposes that biopunk, or slipstream works with a focus on biotech, is the study of living, not the depressing, close-to-extinction fiction of cyberpunk.

Despite his efforts to elevate the genre, much of biopunk still riffs off the dark nature of human experimentation and exploitation, albeit with some positive undertones.

Some prominent novels in the genre include:

- Blood Music by Greg Bear (often seen as an overlap of biopunk and nanopunk)

- The Xenogenesis trilogy by Octavia E. Butler

- Schismatrix by Bruce Sterling

- The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

But, the biopunk genre extends farther than the written word, encompassing visual mediums like film and video games.

- The BioShock game series

- The 2009 film Splice

- The Resident Evil game series

- The TV show Orphan Black

Blade Runner, the 1982 film based on Philip K. Dick’s book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is often categorized as a cyberpunk work, which in many ways, it is. However, it does feature biopunk themes. The Replicants, sometimes thought to be androids, are actually biologically-engineered, clone-like entities. This becomes clear in Blade Runner: 2049 with the scene Replicant-birth scene.

A Sci Fi Subgenre With Substance

Biopunk started out as an offshoot of cyberpunk, but in many ways, it has overshadowed its predecessor. The dedication to the ideological expansion of biotechnology and its implications to the everyday person makes biopunk a much more digestible genre than cyberpunk.

While we’re closely catching up to the cyberware featured in the cyberpunk arsenal, biopunk hits closer to home. Everyday we see incredible advancements in genetic engineering and biochemical panaceas that make biopunk’s darker ideations much more realistic and haunting.

What do you think? Will biopunk outlive its predecessor? Or will our biotech surpass the bounds of imagination?

Let us know in the comments below!