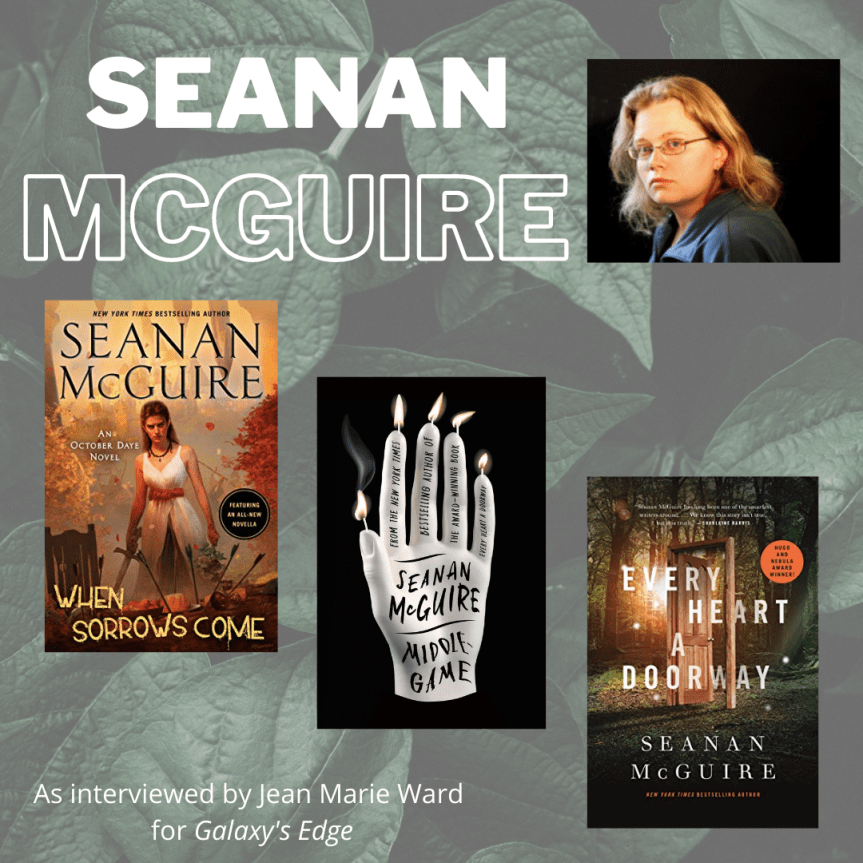

In the July 2021 issue of Galaxy’s Edge, Jean Marie Ward interviews Seanan McGuire. They discuss all manner of things, including writing, publishing, feminism, and much more!

Check out the full interview below, and if you like this content, consider subscribing to Galaxy’s Edge, where we bring you the best speculative fiction from writers new and old, as well as thoughtful interviews and book reviews.

About Jean Marie Ward

Jean Marie Ward writes fiction, nonfiction and everything in between. Her first novel, With Nine You get Vanyr (written with the late Teri Smith), finaled in both the science fiction/fantasy and humor categories of the 2008 Indie Awards. She has published stories in Asimov’s and many anthologies and provided an in-depth look into an award-wining artist, with her book Illumina: The Art of J.P. Targete. Her second nonfiction title, Fantasy Art Templates, marries the superb illustrations of artist Rafi Adrian Zulkarnain with pithy descriptions of over one hundred fifty creatures and characters from science fiction, fantasy, folklore and myth. A former assistant producer of the local access cable TV program Mystery Readers Corner, Ms. Ward edited the respected webzine Crescent Blues for eight years, and co-edited Unconventional Fantasy, a six-volume collection of fiction, non-fiction and art celebrating the fortieth anniversary of World Fantasy Con. She has also contributed interviews and articles for diverse publications before starting interviewing for Galaxy’s Edge magazine. Her website is JeanMarieWard.com.

FOLKLORE, PLAGUES, AND ANGLERFISH

What are award-winning, SFF writers made of? In the case of Seanan McGuire—author of the October Daye, InCryptid, Wayward Children series and more under her own name, as well as the science fiction horror novels of her alter ego Mira Grant and the children’s fantasy she writes as A. Deborah Baker—the answer encompasses music, art, anglerfish and 3 a.m. fanfiction attacks. Strange as the recipe may seem, you can’t argue with the results. To date, McGuire’s honors include the 2010 John W. Campbell Award (now the Astounding Award) for Best New Writer, the 2013 Nebula Award for Best Novella, five Hugo Awards, a record-breaking five Hugo nominations in a single year, and five consecutive Hugo nominations for Best Series—to say nothing of the seven Pegasus Awards she’s won for her filking. Eager to learn more, Galaxy’s Edge sat down with the California native a few days before the release of her latest novel, Angel of the Overpass, to talk about her earliest days as a writer, her fascination with microbial marvels, and expanding the notion of personhood on the page.

Galaxy’s Edge: When did you first realize you wanted to become a writer?

Seanan McGuire: When I found out it was an option. I was a very weird child. I was credulous in some ways that sound fake to me now, even though I remember the experience, and disbelieving in other odd ways. It made perfect sense to me that lunch boxes would grow on trees, which happens in The Wizard of Oz. And if there are lunchbox trees, why wouldn’t there be book trees? I had never met an author. I had never met anyone who said they were an author. I just figured that books happened. Being a storyteller felt like too much of a responsibility for any one person. It didn’t make sense, given the breadth of stories I could experience if I went looking, that anyone would do that.

At the time, one of my favorite shows was an anthology series on the USA Network called Ray Bradbury Presents. Every episode began with this white-haired dude sitting at a typewriter pounding away. Then there’d be a ding, and he would pull a sheet of paper out of the typewriter and throw it into the air. It fluttered down and formed part of the logo.

One day I asked my grandmother, “Who the heck is that? Why is this old dude taking up like a whole minute of what could be story?”

She said, “That’s Ray Bradbury. He wrote all these stories.”

That was my bolt of lightning moment. Wait, one person made all this up? This is all fake, and one person sat down and thought of it, and that was okay? That was allowed? I pretty much decided on the spot that that’s what I was going to do.

Galaxy’s Edge: How did you get from there to your first published stories?

Seanan McGuire: A lot of fan fiction. So much fan fiction. Shortly after the Ray Bradbury Presents incident, my mother brought me this gigantic manual typewriter from a yard sale. It cost five dollars, and it disrupted her sleep for years. It weighed more than I did. I would sit down, feed my paper in, and pound away for hours. I was seven. Seven-year-olds don’t sleep like humans They’re people, but they aren’t humans yet. The idea that 3 a.m. is not a good time to start working on a giant manual typewriter that sounds like gunfire does not occur to their tiny seven-year-old brains. And since the typewriter was so big compared to how big I was, I couldn’t just type, I had to assault the keyboard. I hunt and peck at approximately two hundred forty words per minute…

Because I was writing for hours at night, I would write stories about my cats or what I did that weekend or—and this is key—about having adventures with my friends, the My Little Ponies in Dream Valley. I had no idea that a self-insert was a bad thing. I was seven. I had no idea that saying I would be good at everything the ponies needed me to be good at was being a Mary Sue. Again, I was seven. I did this for years.

The thing about writing is the more you do it, the better you’ll get. You can get good at some really bad habits. But putting words in a line, forming sentences, building sentences into a paragraph, building enough paragraphs onto a page to have a page? That’s a muscle. That’s something that you learn by doing. I turned out reams and reams and reams of not goodness, but it taught me how to put together a page.

Then I got to high school and discovered real fanfic, where you write in a universe. [Fanfic] had these weird unspoken rules, like the Mary Sue Litmus Test, and what was and was not appropriate to do. One of the first pieces of advice I was given was never write a character who looks like you, even if they’re canonical, because everyone will assume that the blonde girl writing about Veronica Mars or Emma Frost is really writing about herself, and that’s not okay. At some point, every dude I know writes about himself having magical adventures in a magical D&D land and getting all the hot elf babes. But if a blonde woman writes a blonde character or a Black woman writes a Black character or anything superficially similar to their appearance, it doesn’t matter how integral that character is to the story, it’s proof they’re sticking themselves in the story, and that’s bad. I disagree with this, in case you can’t tell.

Galaxy’s Edge: What about the little blonde girl in the InCryptid series?

Seanan McGuire: I ultimately got around the problem by making everything fanfic. Verity is basically Chelsie Hightower from So You Think You Can Dance. The InCryptid series was a response to my PA saying, “Please, write something that gets us invited to go backstage on So You Think You Can Dance.”

But in the beginning I just wrote a lot of fanfic. The more fanfic I wrote, the better I got at things like plot and structure and actually writing a 20,000-word, a 50,000-word, a 100,000-word story that wouldn’t bore my readers. Eventually I started writing original fiction, which pretty much went nowhere. I would write it, I would be happy with it, and then I would revise it, because when no one’s publishing you, masturbatory revision takes 90 percent of your time.

One day, my friend Tara, who knew me from the fanfic community, said an agent friend of hers was branching out and starting her own boutique agency. And because [the agent] was from the fanfic community, she was looking for fanfic authors with an interest in their own original fiction. I sent her a copy of Rosemary and Rue. She sent me back a list of suggested revisions. I did one more revision, and she signed me. Then everything went nuts.

Galaxy’s Edge: Because you had something else in the pipe—something that became the Newsflesh series.

Seanan McGuire: The thing about writing very fast is I write very fast. When we took Rosemary and Rue to DAW, I had already finished [the] first three books in the October Daye series (Rosemary and Rue, A Local Habitation and An Artificial Night). I also had a rough and not-so-great draft of Book Four, Late Eclipses, but I had time to revise and beat it into a shape. I also had Feed, my biotechnical science-fiction thriller. We took Feed to Orbit.

With DAW, we were very fortunate in that a good friend of mine was also a DAW author and able to give me the nepotism referral to her editor. She wasn’t inappropriate about it. She just said, “This is my friend, Seanan. She wrote a really good book. I think you’ll like it. Let me introduce you.”

At Orbit, we went through a more normal submissions process. We wound up with DongWon Song, who’s now an agent but at the time was an Orbit editor. They were the perfect editor for that series. I miss working with them.

Galaxy’s Edge: You mentioned in another interview that you took the “dragon major” in college: a double major in folklore and herpetology. How did that play into your writing and your day job?

Seanan McGuire: I’ve never had a day job that used either parts of my degree. I think that anything we do or are interested in will play into our writing. We can’t help it. It’s part of why I get kind of angry on a personal level at authors who say that fanfic is bad and you can’t do fanfic ever. Well, okay, I’m gonna go over your work and find every element that you took from Shakespeare. How dare you write fanfic? I’m gonna find every element you took from Austen or from Poe. Or from fairy tales, from the Brothers Grimm, from Disney.

Humans are magpies. We do not thrive on original thought. That’s not how we’re constructed. If you have one truly original thought in your entire lifetime, you’re about average. You’re doing well. We want to think of ourselves as these incredible original innovators of everything, but that’s not how monomyths work. It’s not how human psychology works. Everything’s a remix.

Because I studied both the so-called soft science of folklore and the hard science of herpetology, I have, to a certain degree, the flexibility of thought arising from two very different disciplines. It doesn’t make me better or worse than anyone else. It just means that I have been trained to look at things from those multiple angles. There are still ways of thought that are completely alien to me. I have no experience or background in any kind of physical handiwork. I don’t know how to fix a car. If you hand me a hammer and a nail, the odds are good that what I’ll hand you back is a trip to the ER, because I have just broken my hand. There are patterns and ways of thought that I can’t wrap my head around. But having that initial flexibility made it easier for me to switch gears as I got older.

You can see the dichotomy in the two sides of my work. When I write as Seanan, I tend to write very monomythical, very inspired by folklore, very poetic. One of my favorite copy editors says, when you copy edit my work for flow and for tone, you need to remain aware of the fact that I have never written a book in my life. What I write is 300-page poems. That’s not inaccurate. The way I build sentences, the way I phrase things and manage the rising action very much reflects the fact I was a folklore major who studied oral histories for a long time. Within a single book, there will usually be one or two phrases that I hit very often. It’s not because don’t I think my readers are clever; it’s how I assemble a narrative.

When I write as Mira Grant, [the stories] are very biological. I started out wanting her to be a horror author. It turns out she’s not, because I am so much less interested in the screaming than I am in the scalpel. I want my science to make sense, and I want my biology to make sense. That’s what makes me happy.

Galaxy’s Edge: Even when dealing with mermaids?

Seanan McGuire: Even when dealing with mermaids. The mermaids [of Into the Drowning Deep] were actually a direct attack on DongWon. When they were my editor, I would threaten to write them a book about anglerfish mermaids.

The way anglerfish reproduce is the male anglerfish will be attracted by the smell of the female anglerfish’s pheromones. He thinks she’s so sexy that, when he finally finds her, all he wants to do is eat her. So, he chomps onto her skin. This causes a chemical reaction which melts his skin and fuses him with the female. Her body will gradually absorb his until all that’s left is his scrotum.

The female now has a pair of testicles sticking out of her, and she can control when sperm is released. One female anglerfish can have hundreds of sets of testes stuck to her from men that she has effectively eaten. In terms of size, the male anglerfish is about one and a half to two inches long. The female anglerfish is the size of an alligator snapping turtle. It’s one of the biggest cases of sexual dimorphism in the vertebrate world…. The biology of my mermaids was preset by that horror.

Galaxy’s Edge: You didn’t work in herpetology, but I understand your former day job used a lot of your science background, which contributed to Feed and your all-too-plausible zombie apocalypse.

Seanan McGuire: Yep. I am a prophetic genius. The entirety of COVID-19 has been an exciting game of people telling me: “You were right about everything two years ago.” Yes, I was. Thank you. There you go.

Galaxy’s Edge: Are there more such prophecies in our future? Should we be shivering in our boots?

Seanan McGuire: Right now, I am not doing anything super pathological, in part because I lost a lot of optimism in the current pandemic.

People ask me all the time, “What do you feel like you got wrong? What would you do differently?” The answer is I had too much hope. Part of that is Feed was written and published before the real rise of Facebook, before the rise of microblogging, [at a time] when if you wanted a blog, you still had to set up a blog and usually wrote longer-form things. Readers could get an idea of who you were, your likes, your dislikes, your prejudices. You weren’t just delivering speedy sound bites of hatred and vitriol.

I like the flexibility and speed of Facebook and Twitter in terms of things like coordinating disaster response. But what we’ve seen is we’re not doing as much as we could, because we’ve all learned to hate each other in this time of super-fast microblogging, botnets and trolls.

There was a point, early in the current situation, where I posted a thread on Twitter (which is my primary habitat most of the time) about ways to protect yourself from con crud and the seasonal flu. There is a tweet in that thread which can be seen as equating coronavirus with airborne diseases.

At the time, the official position was that the disease we’re dealing with now was not in fact airborne, even though anyone who had ever worked with any coronavirus anywhere was saying, “No, it’s probably airborne. If you don’t think it’s airborne, you’re probably wrong.” The science said, “Probably airborne,” but the official public information said, “Not.”

So, I posted this tweet. It’s in the middle of a relatively innocuous thread. Hey, wash your hands, drink lots of water, sleep. I know that you don’t feel like those last two have anything to do with your health at a convention, but they genuinely do. The more well hydrated you are, the less likely you are to pick up most common crud. That sort of thing. For three days I got barraged by trolls screaming at me for being so irresponsible as to imply that this could be an airborne disease. They weren’t real people. None of them had existed on Twitter prior to a month previous. They weren’t there to engage in conversation. They were there to yell at me. That’s because it’s so easy to set up a word finder, something that triggers off a keyword and unleashes this tide of hating on people who say things you don’t like.

My pandemic response [in Feed] was founded on the idea that the news would lie to us (which we saw will happen), and that in the absence of the news, citizen scientists and citizen reporters would rise as a source of credible information. Instead, what we saw is people will rise to sell you miracle cures made from mercury and tell you that your children have COVID because they were given a vaccination twenty years ago, even though your children are eleven. It’s just bad.

I am not currently working on any diseases because part of what I enjoy about writing pandemic fiction, why it makes me happy to be Mira Grant, is that diseases fascinate me. I find them really interesting—the mechanisms by which they work, the things that we know they can do to us, the things that we’re still finding out they can do to us. They’re amazing. They’re so simple. They’re not living things. They’re basically malware. They’re just these little instruction bundles that plug into your body and go haywire.

It is easier for me not to be afraid of them if I understand them and am writing about them and having a good time. It feels a little mean to have a good time with diseases right now. The way I have always coped with the horrible diseases I created was by going, “No-no. Once enough people started dying, we would care. Once enough people were at risk, we would care.” But what I’ve seen is that far too many of the people in positions of power wouldn’t.

Galaxy’s Edge: There are those who say, if this world fails us, we should write the world we want to live in. What would that world look like for you?

Seanan McGuire: The way I would like the world to be is incredibly overly optimistic. I don’t think we’re going to get there in my lifetime. We have enough food that no one needs to be hungry. We have enough resources that no one needs to be homeless, no one needs to be sick. We have enough of everything that no one actually needs to feel like they don’t have enough. But there is a point at which anything stops being the thing itself and becomes counting coup. There are people with so much money, they could be spending money every minute of every single day of their lives and not come even remotely close to running out of money. And what do they do? Do they rent Disney World for a month? No. Do they set up a zoo full of tigers in their basement? No. They make more money because they have seen how much they are willing to exploit the world, and they want to make sure there’s no one in a position to exploit them.

I want a world where rich people pay their fair share, where everybody gets safe housing, food, clean water, medical care. Where the color of your skin is not treated as any kind of judgment on your personal character. Where the fact that people love who they’re gonna love is not treated as some kind of judgment on their character. It’s so idealistic. Every step forward is amazing, but we have the potential, as a species, to be so much better. Sometimes we aren’t because it would be inconvenient to be better right now. Sometimes it’s because we don’t want to, or it would be hard or “How can I feel like I am better than you if you have as much as me?”

Galaxy’s Edge: As opposed to seeing equality as a valid goal.

Seanan McGuire: We’ve been unequal for so incredibly long that equality really does feel like oppression to a lot of people who have been on the top of the inequality pyramid.

Galaxy’s Edge: Your fiction celebrates diversity and inclusivity. Is this your way of making the world you write shinier, or is it something that just happens?

Seanan McGuire: A little bit of both. But mostly it’s that anything that is 100 percent straight, white, and able-bodied is unrealistic unless you want to set up a bunch of oppressive structures I have no interest in writing.

The world is not a monoculture. Humanity has never been a monoculture. [A lot of stories] treat humanity like a monoculture where any setting you want to use is just pretty stage-dressing and any character you want to design needs a reason to be something other than what we jokingly refer to as the “Six-fecta”: straight, white, vaguely Christian (but not too Christian; you can’t be too religious) able-bodied, cisgender and male. So many books in our genre still hit all six of those attributes with every main character. The only exceptions are some secondary characters who are women because, otherwise, how do we reward the men for being awesome?

But that’s not the world I live in. I have been a queer, disabled, half-Roma woman for my entire life. I knew I liked girls from the time I was eight. Not in a sexual way but in a “If I’m gonna hold hands with somebody and kiss them” way, I would prefer it be a girl. So I can absolutely say that I was queer when I was eight. I’ve been half Roma since my daddy knocked up my mom in the back of a van, and I’ve been female since I popped out. I’ve done the gender interrogation you’re supposed to do as a cis ally and determined that “girl” is pretty much the label that works for me.

I never had a shot at that Six-fecta if I wanted it. Why would I, as someone who deviates from that “norm” on multiple levels, want to write that norm? I know people who fit it, I love people who fit it. I am not saying there’s anything wrong with them wanting to see characters who look like them. But sometimes I want to see a character who looks like me, and that means a character with multiple overlapping identities all of which inform her daily life.

Sometimes, people I know will tell me they want to see a character that looks like them, and they don’t get to do that very often. Then I will make a genuine effort to include a character that looks like them, because I want them to have that experience. We learn how to human from stories. Like I said before, humans are not built for constant original thought. We learn what a person looks like from the stories people tell us. Sometimes that is learning: “Wait, that’s me. I’m a person.” And sometimes it’s learning: “Wait, that’s Jean Marie. Maybe she’s a person too.”

Culturally, we have done ourselves a huge disservice by telling so many stories for such a long time where the only people who got to be at the center of the story were the ones who fit those six attributes, because only those people get fully acknowledged as people by the monomyth we’re living in. That’s not fair and not okay. The only time I tend to manipulate the diversity in a story is if I realize I need to kill somebody. If a group has little representation, you can kill a much larger percentage of that group by killing one character. If I kill a straight white man in science fiction, I have killed one of ninety million straight white men. If I kill a trans woman in science fiction, I’ve killed one of maybe twelve. That’s a very different statement, whether or not I intend to be making it.

So, if someone is in the line of fire and I cannot move them, I will stop, look at what I’m doing, and ask myself: How big a deal is this character to the group they represent? How big a deal would it be if I were reading this book and that character looked like me? Would I have seen me before? That’s not tokenism. I don’t give plot armor to these characters. They can still die. It’s a matter of am I taking away someone’s emotional support character?

Galaxy’s Edge: You have explored just about every subgenre in speculative fiction. Is there any particular kind of story or genre that you would really like to write but haven’t had the chance?

Seanan McGuire: I have an intense, bordering on the ridiculous, fondness for mid-Nineties chick lit, the sub-genre where The Princess Diaries, The Boy Next Door, and Bridget Jones’s Diary live. I’m waiting for the nostalgia wave to whip those back around. I’ve written several. I’m pretty good at it, but there’s no market for them right now. So they sit and occasionally get revised, when I have time, to make sure that they stay up to my current standards. And they go nowhere.

I would also very much like to write a series of cozy mysteries—The Dog Barks at Midnight sort of thing. I have a concept for a fun series of cozy mysteries. But unfortunately, I am told by both my agent and several authors I know who write cozy mysteries, there is no money there. There’s just none.

It’s not that I only write to chase the money, because no one becomes a writer to chase the money. That is the worst decision you could possibly make. Don’t do that, children. Or adults. Or unspeakable cosmic entities. Don’t become a writer because you want to get paid. You will not get paid. But there is a difference between writing something I am truly passionate about, cannot stop myself from writing, that I already know I’m good at, and not getting paid; and writing books in a genre I find charming but not completely compelling, kind-of-wanna-try-my-hand-at but will not get paid. One is a reasonable self-limiting decision. The other is just not bright.

I’d also like to write a truly horrific horror novel that has no science fiction elements. Just horror. I wanna do horror for the sake of horror. I wanna get my Clive Barker on. I wanna get my Kathe Koja on. I can’t. Every time I try, I get distracted by the possibility of science.

Galaxy’s Edge: That’s tragic. Science is death to horror.

Seanan McGuire: Yeah, I love horror so much, and I’m so bad at it.

Galaxy’s Edge: Any closing thoughts?

Seanan McGuire: We are recording this on April 29, 2021. I have a book coming out on May 4 called Angel of the Overpass. It’s the third book in my Ghost Roads series, which is InCryptid-adjacent, published by DAW Books. I won’t say it’s the last, but it is likely to be the final entry in Rose Marshall’s story for a while. So I’m very excited about that.

Over on my Twitter, I just finished a complete review of the October Daye books, because they are nominated for a Best Series Hugo this year. Having grown up in fandom, I tend to be very careful and a little aloof when talking about the Hugos. I remember being told by my foster mother when I was a teenager that it’s gauche to say you want to win. But I really want to win this year.

I feel that the Best Series category was created for urban fantasy. I know it wasn’t created just for urban fantasy, but urban fantasy plays best at series length. It is a story that needs that room to grow and breathe and really be considered as a whole, not just as the sum of its parts. I would desperately like for the first true urban fantasy—just urban fantasy, not urban science fiction, not urban horror, but urban fantasy—Hugo to go to a female or female-identifying author. It’s the only science fiction subgenre that is female-dominated and doesn’t have the word “romance” somewhere in the description. Romance is great. I love romance. I write romance. But female authors get shoved into romance so quickly, whether or not that’s what we want to be doing. Having a subgenre we currently control has always been very very important to me. It feels like a thing we have accomplished as ladies.

So, I would like the first Hugo Award given to a work of pure urban fantasy to be given to a female-identifying author. It doesn’t have to be me. You have many other choices. We are a big and diverse field. But if you’re looking at this year’s ballot, it does have to be me.

Galaxy’s Edge: We’ll keep our fingers crossed and hope the best.

Seanan McGuire: Thank you.

Like our interviews? Read our conversation with qntm, author of There Is No Antimemetics Division!

Nancy Kress

Nancy Kress