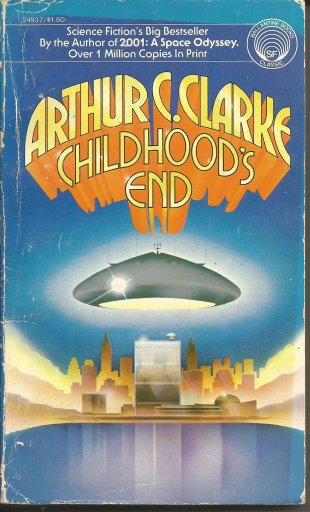

Recently, I’ve been reading Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, and I was struck by how old it seems. For me, at least, the true measure of an older science fiction novel is if it manages to maintain a certain level of credibility within the logical timeline I have running in my head.

Like, I read Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany, and yeah, it was published 60 years ago, but it never succeeds in placing itself anywhere in a coherent time or space I’m familiar with. There’s no bending of history to accommodate this novella, everything Delany writes could have happened, or still could happen in the future.

But with books like Childhood’s End, I can’t help but think about how it’s lost that security of time and special awareness. The book, published in 1953, starts out with US and Russian engineers in a race to put a military spacecraft into orbit. The way Clarke spins this, he makes it seem like it’s a big deal. The first craft in space! And he probably succeeded in hyping up his audience in 1953, because at that time the US and the USSR were in the middle of their Cold War rivalries.

As readers in 2022, however, we know that in 1957, Sputnik becomes the first space satellite to orbit the Earth. When Clarke’s timeline in Childhood’s End jumps forward, we present-day readers have to suspend our beliefs in order to keep going.

Dispelling any knowledge of the future as we know it after 1953 is sort of the antithesis of Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. We have to erase our minds and our beliefs to read Childhood’s End as a science fiction novel, not as an outdated alternate history.

And it got me thinking about near future sci fi books in general. In how many years will we look back at science fiction books and movies that speculated on our near future and say “nah, that’s just not it”?

Or, will we engage in the active purging of our memories when reading these books to accommodate the timeline and scenarios that may have already come to pass, whether true or not?

How Near Is the Near Future?

Obviously, science fiction spans across multiple different subgenres and niches, some of which specialize in far future scenarios, thousands of years after humanity will be dead and gone. Others hit closer to home, waxing clairvoyant about ten, twenty, or fifty years into the future.

Some sci fi concept novels or movies make a point of clearly specifying a time and place of the story, so much so that the time has become part of the story’s identity.

Blade Runner: 2049, for example, or even Cyberpunk 2077. These works make the time in which they’re situated part of the premise. Just thinking about the future will get people to consider these works as the blueprints for the years 2049 or 2077.

Other works get even closer to our current time in space. The Martian predicts colonization efforts on Mars by 2035, while Constance brings human cloning to the forefront in 2030.

As these authors get closer and closer to our present day, the likelihood of their speculations coming to fruition gets smaller and smaller.

Near future sci fi books act as a kind of playful challenge to the science community. “Do you think you can perfect human cloning and commercialize it by 2030? I bet you can’t.”

But here we have to dive a bit deeper, look directly into the face of the question: what’s the purpose of near future sci fi, anyways?

The Art of False Predictions

Cory Doctorow talks about how sci fi authors predict the future in an essay that was published as part the Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds. An excerpt was published on Slate.com, where he notes that:

“When it comes to predicting the future, science-fiction writers are Texas marksmen: They fire a shotgun into the side of a barn, draw a target around the place where the pellets hit, and proclaim their deadly accuracy to anyone who’ll listen.”

And he’s right. Sometimes a sci fi author will get wildly lucky and hit the nail on the head, winning the million-dollar prize and fame forever.

But most times, predicted, imagined futures will pass us by every day without any grand hoorah, ending up in a catalogue of unfulfilled timelines.

And then there’s the in between-realm. The few science fiction legends who had enough common sense and foresight to predict what our future would be like in the next 50 to 100 years. Arthur C. Clarke predicted 3D printing, Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick predicted something like the internet that would connect the whole world.

But, here’s the fun part. These guys, they’re still shooting that double-barrel shotgun from the hip with a Sharpie in their teeth.

It’s easy to make a broad speculation about the future based on events in the past and the current state of science.

For the Golden Age sci fi writers, looking back at the technology of their childhood, and then looking at the world they were living in, it must have been fairly easy to assume what was coming next. Radio, telephones, television—those things were shaping the world in sci fi’s heyday. To look forward and think about a more advanced transfer of information from person to person, a method that’s faster, is only natural.

Does that mean Clarke, Asimov, and Dick predicted Facebook? Absolutely not.

And I think that’s where we find the answer to our titular question: Will near future sci fi books lose their luster?

The Devil’s In The Details

The reason I started thinking about this question of longevity of sci fi books is because Childhood’s End made me recondition my knowledge of history to read it without skepticism. The future for Clarke is distant history for me.

And I assume people in the year 2060 will look back at Blade Runner: 2049 and laugh, knowing that their lives are either much better or much worse than they were imagined to be back in 2017.

Films and books like that, in this regard, made the mistake of being too specific. The first rule of sci fi predictions is to never timestamp anything. Had the film been named Blade Runner 2, perhaps people might have been able to extend the possibility of a near future where Replicants and Blade Runners walk the streets.

The Golden Age crew thought up something like the Internet, but they didn’t specify when it would be created, who was going to do it, what it would be called, etc. So, in many ways, they were right.

I guess what I’m trying to say is that near future science fiction books will always make predictions about a time and place and a technology. When we come across a book like Childhood’s End where we as the reader are required to willfully ignore recent history for the sake of the story, just know that that author fell prey to the camp of specificity.

And we can’t wholly discount these once-could-have-been-futures, either. In 2060, we’ll probably look back at The Martian, Constance, Blade Runner, all of them and take something from them. It won’t be a slice of science history, rather a note about the human experience, something we can relate to even though we might be living in a world none of our sci fi authors could have imagined.