The new year brings with it a new issue of Galaxy’s Edge Magazine! This month’s lineup includes authors Harry Turtledove, Effie Seiberg, Galen Westlake, Wang Yuan, and more!

Plus, Jean Marie Ward sits down for an interview with prolific sci fi legend, John Scalzi.

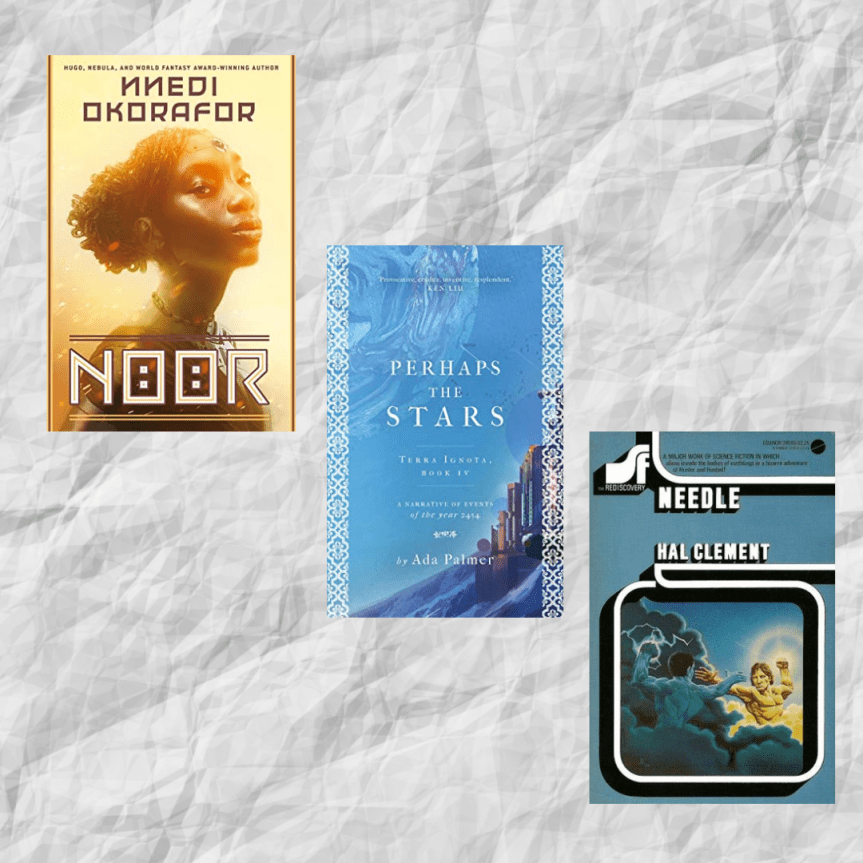

And Robert Chwedyk is at it again with another round of sci fi book reviews, this time including:

- Perhaps the Stars by Ada Palmer

- Noor by Nnedi Okorafor

- Needle by Hal Clements

Check out what he had to say about these books below!

Perhaps the Stars

by Ada Palmer

Tor

November 2021

ISBN: 978-0-7653-7806-4

This was the work I was most hoping to get my hands upon when I entered the dealers’ room. It’s the “culmination” (it says so on the cover) of Ada Palmer’s massive tetralogy, Terra Ignota. And it fulfills the promise of the earlier books, Too Like the Lightning, Seven Surrenders and The Will to Battle. This is science fiction conceived of as a “literature of ideas,” and then raises the stakes to something that seems to dwarf such terms as “literature” and “ideas.” It’s a novel that not only contains the heart of a person or group of persons (a cast too numerous to even hint at), it contains the heart of an entire age. An age to come.

That age, to the surprise of some, is a renaissance transported centuries ahead of our time.

And why not? Writers like John M. Ford and Jack Dann have transported science-fictional concepts and sensibilities to alternate versions of the Renaissance. Why not the other way round? It was an age of great discoveries and brutal struggles for power and influence. It was era of great art and murderous passions. It was an age marked by both progress and the threat of ultimate calamity. Describing it that way, it sounds like the milieu of an Alfred Bester novel, or Cordwainer Smith with a crueler streak. And that’s not a bad way to summarize Palmer’s Terra Ignota milieu, except that Palmer raises the stakes a few nth degrees. Palmer’s world reinvents and somewhat refines technologies that have existed for centuries, were lost, and invented yet again. More important than technologies in some ways are the reinventions of ideas, like humanism, since the Renaissance can also be considered to some degree a humanist revolution.

It was also a most forward-thinking era. An impressive number of its luminaries could be mistaken for science fiction writers (and very often are). Also very much present in Palmer’s imagined future is the presence of the classical myth and epic imagery which energized and inspired the historical renaissance.

Those are just some of the aspects of renaissance culture Palmer so splendidly re-tools and extrapolates to thrilling effect, which may sound strange, since much of her prose is dense in texture. It is not, however, impenetrable. On the contrary, it draws you in and sustains your attention.

No matter how alien (in the widest sense) and far-out her scenarios and speculations may get, there is something familiar about them that we can connect with. Science fiction is often complimented (and also castigated) as a literature of ideas. Palmer is one of those writers who can bring those ideas to life in myriad, and fascinating, ways. It is more than intellectual exercise. In her hands, it’s emotionally compelling too. The novel pulls you in and sustains your interest throughout.

There is no one else in the field now (or at any time before) writing like Ada Palmer, which some readers may think a pity and others a blessing. The good news is that one Ada Palmer is sufficient (and necessary), and we’re very fortunate to have her.

Noor

by Nnedi Okorafor

DAW

November 2021

ISBN: 978-0-7564-1609-6

Of recent, Nnedi Okorafor has branched out into writing comics and screenplays, but what I still love best are her novels. She has not only invented a whole new way of looking at science fiction, but in doing so not only invented a voice, but a new kind of voice. Her worlds are as distinct in their own Africanfuturist (which Okorafor distinguishes from “Afrofuturist”) way as are the worlds of a Cordwainer Smith or an Alfred Bester or a R. A. Lafferty or a James Tiptree, Jr. are to theirs. I know, she has received much acclaim already, but I think her contributions are still undervalued to the field because, simply, so many of us are still learning how to read her.

Her most recent work has us following Anwuli Okwundili, who has shortened her name to AO, though she also insists this stands for “Artificial Organism.” AO was born with severe defects and given a number of mechanical enhancements. We’re in cyberpunk territory, but only in some ways. AO ends up with more enhancements when she turns fourteen, courtesy of the Ultimate Corp. All of this, as you would expect, makes her something of an outcast in her Nigerian village, until the day she is attacked in an Abuja marketplace. She manages to kill all the attackers. Now she is really an outcast, on the run, and she heads for the desert, where she runs into a Fulani herdsman named DNA, who is a lot more than his humble profession may suggest.

Also in the desert they encounter a roving dust storm called the Red Eye (which reminded me, of all things, of the sentient tornado named Sweetiepie that outsider artist Henry Darger wrote about in his autobiography). It is inevitable, especially in an Okorafor novel, that AO and DNA’s journey will bring them into the very heart of Red Eye, and even if you are familiar with any of Okorafor’s recent work, it will not be like anything you expect.

The thing I’ve found about Okorafor’s books is this: whoever you are and wherever you come from, you have to give yourself over to her and let her work her (in some cases literal) magic on you. With some authors this would be a dangerous proposition. Not so with Okorafor. Not only does she give me a plethora of new places to see, she lets me see them from angles I never would have imagined before. I trust her even when I have no clue what she’s doing because I’m certain she damn well knows what she’s doing, and that’s good enough for me. That feeling, that trust, is one of the things that got me reading science fiction in the first place.

Needle

by Hal Clement

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

1950 (first printing; many editions followed from several publishers)

ISBN: 0-380-00635-9

As much as I love all the new releases, my favorite part of the dealers’ room are the tables and tables of second-hand books, especially the mass market paperbacks. Were it not for those little gems calling out to me, siren-like, from the spinner racks of pharmacies and department store displays all those years ago, I might not have lost my heart to science fiction, at least at such an early age.

At the convention, I was fortunately able to acquire a copy of Hal Clement’s first novel, Needle, which I loaned out to someone who had the good sense never to return it. Clement hasn’t been given much attention in a long, long while, though he is occasionally remembered via lip service as one of the founders of “hard” SF. When mentioned, it is usually in regard to his best-known novel, Mission of Gravity.

I can’t say which novel is objectively better, but I have a fondness for Needle because it not only gives us the prototype for a number of stories where alien life forms take up residence in human hosts, but it does not descend into the kind of horrific scenarios most writers would take this sort of thing. In fact, Needle can also serve as a prototype YA novel, since its human protagonist is a fifteen-year-old boy. It has also been unofficially adapted (aka ripped off) by the manga 7 Billion Needles, along with media variations as far afield as Ultraman, The Hidden and Brain from Planet Arous. If “steal from the best” means anything in our culture, this novel has some real creds.

Robert Kinnaird, the boy, finds himself inhabited by the alien, The Hunter, who, as his name suggests, is in pursuit of a criminal alien. The criminal and The Hunter, both in their own ships, crash land near a sparsely populated Pacific island. As The Hunter inhabits Kinnaird, the criminal he’s pursuing inhabits someone else on the island. But just as The Hunter is learning something of his host, the planet and the culture he now finds himself in, Robert is sent off to a New England prep school. The Hunter not only has to find a way of cooperating with his host, and vice versa, he also has to find a way to get himself (or “themself,” sort of) back to the island so he can apprehend the criminal alien.

The novel works marvelously on several levels. It not only successfully portrays non-humanoid aliens as something other than nefarious invaders and maintains its hard science-fictional pedigree, but it also serves as a metaphorical evocation of the strangeness of adolescence: a boy feeling his body in change, as if something new is living inside him, not quite him but not quite not him. This perceived change gets even pricklier when he returns to the island and we discover who the host of the criminal alien is (no spoilers).

It’s a fable of change and growth and maturation told in the brisk and capable voice that marks the best of Clement’s work.

The discovery of such a gem in any dealers’ room is one of the joys of going to conventions in the flesh.

It felt so good to be back.

May we all be able to do much more of this soon.

Be sure to check out all the other books Chwedyk has reviewed in the January, 2022 issue of Galaxy’s Edge, as well as the great stories from new and established authors alike!