Here at Signals from the Edge we spend an inordinate amount of time talking about sci fi subgenres and the best science fiction shows on TV. But, sometimes it’s important to branch out and explore other speculative fiction.

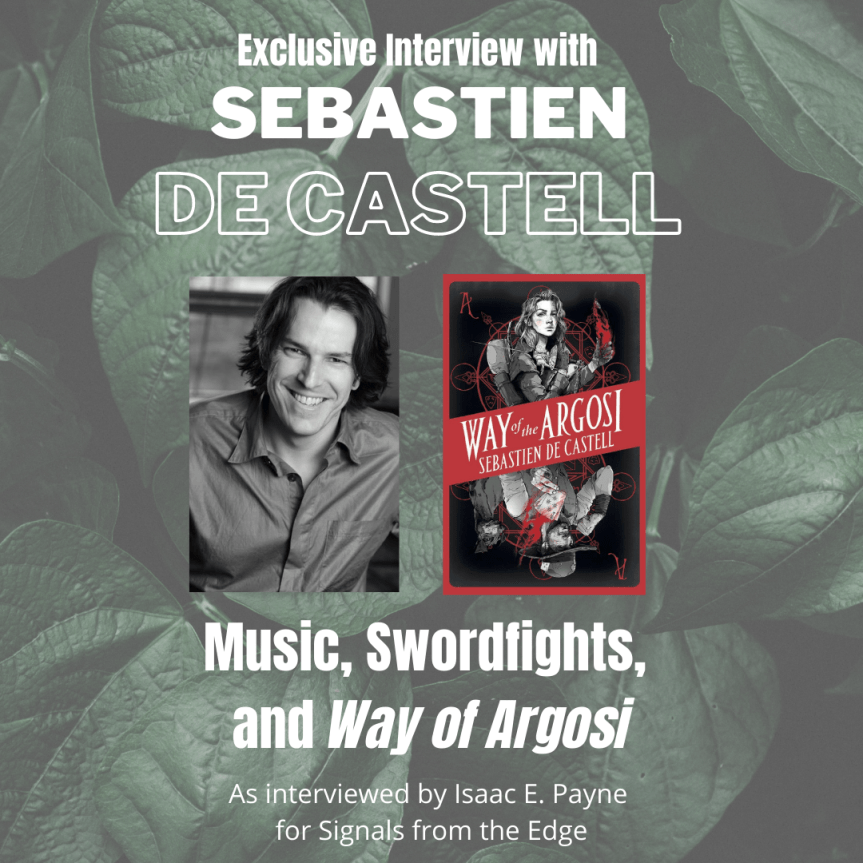

That’s why we met up with Sebastien de Castell, the renowned fantasy author of Traitor’s Blade to discuss his latest novel, Way of the Argosi.

Isaac Payne: How did you get started writing?

Sebastien de Castell: I’m one of those terribly disingenuous writers who barely wrote a thing in their youth and yet always wanted to see a book on a shelf with my name on it. But I didn’t start writing seriously until I was about twenty-seven. I was making my living playing in a rock & roll band, performing songs like “Brown-Eyed Girl” and “Mustang Sally” three times a week. We weren’t making a lot of money; we were surviving. The band started falling apart, I was feeling creatively stifled, so I did what I always do in those situations: I went to the library.

Libraries are like cathedrals to me. There’s no particular god to pray to, but you can always find wisdom there and a path forward. In my case, I found this cardboard box of twelve book tapes by Ralph McInerny, who was quite a renowned mystery author. The cassette tapes were part of a course called Let’s Write a Mystery. It was really bizarre; he speaks like a 1960s science professor while he’s writing a mystery novel alongside you, and yet, somehow, it worked.

I’m one of those people who struggles to follow through on things they start, but Ralph’s patient, plodding voice kept me going. Within a few months I’d written a mystery novel called Skeletons in the Cloister. It was terrible.

But writing that novel was revolutionary for me. It changed the way my brain worked. People seldom talk about the benefits of writing a novel—any novel—regardless of how it turns out. Part of the reason is that we live in the world of self-publishing and so it feels like everyone’s publishing books and therefore the accomplishment seems less notable.

But what I talk about to new writers is that when you struggle through drafting your first book, it changes your brain in the same way that training to run a marathon changes your body. You don’t run a marathon to win your first time, you run a marathon because doing so changes your body into one that can run marathons. It’s incredible.

And writing a novel does the same thing. That process alters your brain into one that can envision and create entire novels. Nothing ever feels quite so difficult after that first book. I honestly thing one of the best ways to advance in your career—whether it’s as a writer, a teacher, tax accountant, or just about anything else—is to write your first novel. Big, complicated problems become far more manageable to a brain that’s adapted itself to writing an entire book.

So, after that first novel I wrote, I was intrigued. Years later, I participated in the 3-Day Novel Writing Contest, and for three days straight I wrote a novel. And, I still had time to live my life; I slept great, I played a gig, I went for a run. And in those three days I wrote 44k words of what would later become Traitor’s Blade and launch my career as a full-time novelist.

IP: That’s such a great story. You know a lot of writers say “Oh, I started writing when I was fifteen and never stopped” but it seems like you kind of had a late start. When did you reach that point after writing your first one or two novels that you realized your dreams of having a book on the shelf was a realistic goal?

SC: I had a strange upbringing because my mother was a bit on the crazy side. When I was 9-years old, right after my father had passed away, my mother brought my brother and I together. She said that our father’s pension wasn’t enough to live on and that she was going to do the easiest thing she could think of to make money, and that was to write romance novels.

It’s a preposterous statement by any measure.

My mother’s sense of romance, as a staunchly British woman who lived through World War II, was that above all else, romance should be sensible. She wrote a couple of books and nobody published them. But somehow, my nine-year-old brain persisted and I always had the principle of “you can do this, it’s just a function of work”.

The greatest unfairness in publishing is that if you’ve been trained by society to think that you don’t fit or that you don’t have anything important to say, you’ll forever be at a disadvantage. In a lot of ways, it’s game of bluster.

When you’re trying to get someone to read your book, you have to have a degree of overconfidence about you. I see people at writing conventions who meet an agent and are terrified to pitch their book. I understand why, but they’re at a huge disadvantage when compared to all the arrogant people who aren’t afraid to take advantage of every opportunity.

You only really get better as you go because you have more life experiences, but you have to have confidence to give yourself permission to take those first steps.

I go through writers’ block a lot and points where I think “I don’t know if this book’s good enough, how did I write this book, it feels like someone else wrote it”. But if you accept that it’s a function of work and keep trying, anyone can write a novel.

When someone says to me, “I’d love to write a novel, but I don’t have the talent”, I ask them, “Can you write a good opening sentence?” I’ve never met anyone who couldn’t write a compelling opening sentence; it just comes down to how many tries you need to get there. The great thing about being a writer is that you can have all the tries you want to get to something beautiful.

You get the opening line, you can write the next line, and then you can write a scene. If you can write a scene, you can write a book.

IP: I saw on your website that you’re pretty involved as a musician, does that love of music inspire your writing of fiction?

SC: Music plays a strong role for me. I’ve been trying to understand myself better, what makes me tick, and I’ve found that music has a profound impact on my mood. As someone who has a tendency for drifting off into daydreaming, music is a potent focusing drug that pushes me towards coming up with actual scenes or characters.

Music is a great way to build up a character in your mind. It’s perilously easy to unintentionally plagiarize characters from books or movies or video games, but songs inspire me to construct characters not just out of the lyrics, but from the performance itself. The melody and rhythms can propel you into imagining a character in a setting that has nothing to do with the literal meaning of the song, and so becomes something new and fresh.

Alternately, a song’s influence on me can be extremely direct. For example, in Traitor’s Blade there’s a thing called the Blood Week, which people tell me is like The Purge even though I’ve never seen that movie. Anyways, Falcio, who is this swashbuckling magistrate, is protecting a young girl who is the target of the killers. He’s forced to stand there while the time ticks down because nobody can do anything until sundown. He’s just preparing for this incredibly difficult fight.

There was this song titled “You Know My Name” by Chris Cornell, and it was the theme for Casino Royale. The song feels like . . . like this swordfight that could unleash at any moment. At one point, before the fight breaks out, Falcio even uses the line, “You know my name.”

So, music has always been both a direct and an indirect influence for me. When I’m really lost in terms of how to make a story work, I’ll go looking for a song to trigger the emotional state I need for inspiration. As a writer you’re always looking for those things that lets you engage with a different state of consciousness. For me music is that method.

IP: For whatever reason while reading your most recent book, Way of Argosi, I got flashbacks to reading David Eddings, specifically The Belgariad. Are you familiar with his work?

SC: I am! I read The Belgariad as a kid and really enjoyed it, though it never turned the way I wanted it to. I was more prone to grudges than Garion was. I remember then he figures out that Polgara, his aunt, has been lying to him about something, and I was so mad. He forgives her two chapters later and I shouted “no way!”.

But that’s interesting, I hadn’t seen parallels between Way of Argosi and The Belgariad, but you’re probably right, because Eddings’ work was one of the few fantasy series I read as a kid.

IP: What does your writing process look like? Are you a one draft and done kind of guy, or do you take multiple drafts to get it the way you want it?

SC: I have the most unsatisfying answer in the world, which is that every book follows a different process.

When I say that, I sound like I’m devising the most perfect process for each book, but it’s the exact opposite: picture a guy who doesn’t know how to go about writing his next book and is waiting for the right plan to appear by process of elimination, having failed all other ways to write it.

Sometimes a book will take me 2-3 years, and I’ll write 8 other books while working on that one. There’s no rhyme or reason to it.

I once wrote a book in a month. It was what I call a “for me” novel. Actually, it has a much less polite name, but let’s stick with “for me” to avoid offending anyone.

In a relatively short career, I’ve had 12 books published and been translated into fourteen languages. I’m incredibly fortunate to be earning a living as a novelist. But as time goes by, you start to get a lot of voices in your head you might not want there: the voice of your agent who is trying to help you on your career; the voice of editors, who in recent years have become increasingly more afraid of publishing anything that might offend anyone for any possible reason. It’s not even about political correctness, it’s more about how words or scenes might be misinterpreted or projected on a current societal problem and viewed as a “response”. And there’s the voices of readers who adore certain characters or hate others or wish you’d write this book instead of that and . . . it all becomes overwhelming.

These voices are usually from people who love your work and want to help you succeed in your career, but it can become very inhibiting. A better novelist than I would ignore it all, but the only way I know how to deal with getting these voices out of my head is to occasionally sit down and write a “for me” novel.

The For Me novel is my way of saying, “I going to write whatever the hell I want”. I allow myself all the tropes, clichés I feel like employing. I don’t give a damn if a scene might be misinterpreted or deemed problematic. It’s my novel, after all, and if I spend the whole time worrying about who will or won’t like it, I’m really writing somebody else’s novel, and that’s just not satisfying.

I meet new writers who get stalled because they’re constantly inundated with declarative statements about what’s cliché, who can write what, who can say or think what. It’s not about where someone sits on the political spectrum, because everyone is being inundated with opinions about what fiction should look like. Maybe some of that is even a good thing to keep us thinking about the effect of our books. But for me, I need a way to reconnect with who I am as a writer, and the way to do that is to write something that has no regard for what’s popular or even acceptable and probably isn’t—and here’s the important part—publishable.

And it’s helpful! For newer writers, the worst thing about trying to write your first novel now, you’re constantly facing these kinds of opinions and statements. If you love Twilight, you’re constantly being told Twilight sucks. But if you love sparkly vampires but Twitter is making you think, “I better not write about that,” then you’re allowing other people’s opinions to deny your creative impulses.

So, whenever I’m asked what my one piece of writing advice is, I tell people to write the book you most want to read, but do it as boldly as you can possibly imagine. Don’t back away from the things you most care about, because if you do, you’ll end up writing a lukewarm novel that doesn’t offend anyone and nobody wants to read.

IP: For new readers who might not have picked up one of your books before, where would you suggest they start with your work?

SC: If you’re an adult reader into swashbuckling fantasy with a dark edge, Traitor’s Blade is a great place to start. It’s a four-book series, with a new series coming out next year.

If you’re more into magic or young adult, start with Spellslinger. It’s a magical fantasy adventure full of trickery, intrigue, and it even has a murderous, thieving, talking squirrel cat.

Way of Argosi is also a good place to start if you’re looking for a one-off book to test the waters. When I finished the manuscript, I was surprised to find it turned out as a sort of YA fantasy Dickens novel.

If you’re into audiobooks, all my books are in audiobook format. I’ve been blessed to have two of the best narrators in the business: Joe Jameson and Kristin Atherton. I literally cried when I hear Kristin’s reading of Way of Argosi.

IP: What kind of projects are you currently working on? And can readers expect to see more stories from the Greatcoats or Spellslinger universes?

SC: The Court of Shadows is a new series set in the Greatcoats universe, it takes place right after the events of the first Greatcoats quartet. It delves a bit more into magic than we’ve seen in Greatcoats, and a bit more intrigue as well.

When I was talking with my editor about this series, I said let’s do something that’s like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, where you can watch it in any order you want. I hadn’t really seen that done in a fantasy series, (though it probably has been and I just haven’t come across it), but I wanted to explore that dynamic.

You’ll be able to read the first four books in any order. You meet these characters on their individual journeys and see them come together in the final, team book. Or, conversely, you can read the team book first and then go back to see each character’s origins. Sort of like watching the Avengers movie and then going to watch the previous films.

IP: So, Our Lady of Blades is the first book coming out in this new series?

SC: Yes, Our Lady of Blades is coming out in September, 2022. Originally, Play of Shadows was supposed to come out first, it’s already done, but then we decided it made more sense for Our Lady of Blades to be the first book we release.

Our Lady of Blades is an unusual book for me. Usually my main characters are reacting to someone else’s schemes, but this one features a mysterious duelist who comes into the story and sets her own plan into motion. As the story progresses, we learn more about her origins and the larger conspiracy that’s threatening one of the duchies in the world of the Greatcoats.

Thanks so much to Sebastien for taking the time to talk with us! You can find out more about his work and purchase his books on his website. He loves to hear from readers, so if you have a burning question, hop on over to his website or social media and let him know what you think!

If you liked this interview, check out some of the other interviews on Signals from the Edge: